by Kristin Dispenza, CSI

Installed in applications ranging from warehouses, retail, and residential settings, polished concrete floors are no longer a novelty. They are economical, durable, and aesthetically appealing, and have come into standard use over the past few years. However, what has not become standard is a set of unified terms or policies to aid in the specification and communication between contractors, architects, and building owners.

The absence of a unified set of terms and policies has an impact beyond ease of communication. It can have adverse consequences with regard to the equipment and/or processes used to construct a floor in the field and ultimately with how the quality of the finished floor is measured.

The Concrete Polishing Association of America (CPAA) is addressing this issue. In early 2013, the industry group released both a glossary of polishing terms and a set of six position papers elaborating on the definitions. To develop the new terminology and standards, the CPAA Standards Committee—reflecting a cross-section of the concrete polishing industry—identified and reviewed various existing terms and testing methods. They developed a set of recommendations that were voted and agreed upon by the CPAA’s board of directors. Their efforts should significantly advance the cause of creating industry-wide concrete polishing standards.

![A Level 3 finished gloss was achieved on the floor of the Joe Cooper Ford car dealership in Tulsa, Oklahoma. [CREDIT] Photo courtesy Ardor Solutions Inc.](http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/CPAA-Ford-1000x666.jpg)

Since the industry is so new, there is a need for organization and the development of standards.

Burns points out the driving force behind these initiatives are to give architects and designers the tools they need to specify product, rather than a process.

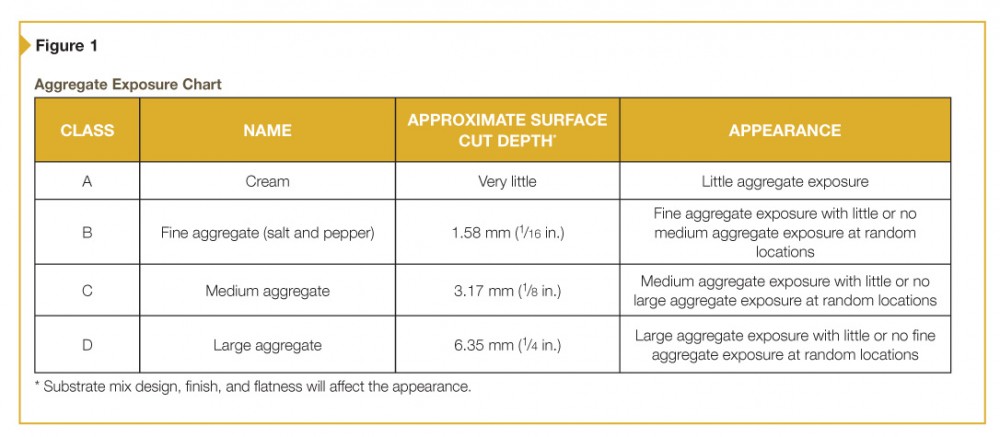

There are more than 50 terms and definitions commonly used with processed and polished concrete, including 12 introduced earlier this year.1 The new terms range from a basic definition of polished concrete to information more technically sophisticated. The tables included in the article include classifying aggregate exposures and finish gloss level information (Figure 1).

As part of its core mission, CPAA continues to develop standards and guidelines for the concrete polishing industry. Its next initiative will be to further develop testing methods for polished concrete.

Burns explains the intention is to create a test method to meet the criteria outlines in the definitions so the design goals can be achieved with quality products.

New polishing industry terms

CPAA defines polished concrete as:

the act of changing a concrete floor surface, with or without aggregate exposure, to achieve a specified level of gloss using one of the listed classifications: Bonded Abrasive Polished Concrete, Burnished Polished Concrete, or Hybrid Polished Concrete.2

Bonded abrasive polished concrete involves a multi-step operation of mechanically grinding, honing, and polishing a concrete floor surface with bonded abrasives to cut its surface and refine each cut to the maximum potential to achieve a specified level of finished gloss as defined. This yields the most durable finish and requires the least maintenance.

Burnished polished concrete involves the mechanical friction-rubbing of a concrete floor surface (with or without waxes or resins) to achieve a specified level of finished gloss. This operation yields a less durable finish and requires more maintenance than bonded abrasive polished concrete.

The association defines hybrid polished concrete as a multi-step operation—using either standard grinding/polishing equipment, lightweight equipment, high-speed burnishing equipment, or a combination—to combine the mechanical grinding, honing, and polishing process with the friction rubbing process by employing bonded abrasives, abrasive pads, or both, to achieve the specified level of finished gloss.

Surface-coated concrete does not conform to the definition of polished concrete as per CPAA. It is the operation of applying a film-forming coating to a concrete floor surface to achieve a specified level of finished gloss. Durability depends on the quality of the chemical coating used, the amount of traffic across the floor, and floor maintenance.

![A polished concrete hallway for Sky Ranch in Van, Texas, was completed with finish falling within the ranges specified for the Level 3 finished gloss. [CREDIT] Photo courtesy USA Floor Tec Inc.](http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/CPAA-hallway-666x1000.jpg)

Grinding a concrete floor surface with bonded abrasives achieves a specified class of exposed aggregate—A, B, C, or D.

A concrete floor surface must be processed to achieve the specified level of finished gloss before application of any protective treatment. Flat (ground), satin (honed), semi-polished, and highly polished are measured in reflective clarity, and reflective sheen (specular gloss).

Reflective sheen has been the standard for measuring the quality of a finished floor. However, it can be deceptive, and is easily manipulated with coatings. Architects and designers need to be aware of this to be able to demand better quality floors, which offer longer lifecycles. Finished gloss is classified as Levels 1, 2, 3, and 4 with varying degrees of reflective clarity, and sheen as shown in Figure 2.

The gloss is measured by a determination of specular gloss that incorporates distinction of image, haze, and Rspec (i.e. the peak gloss value over a narrow angle).

Reflective clarity refers to the distinction of image (DOI) value of the reflection of overhead objects. The degree of sharpness and crispness is measured by a device, such as a gloss meter which incorporates other test functions such as DOI, haze, and Rspec, in accordance with ASTM D5767, Standard Test Methods for Instrumental Measurement of Distinctness-of-image Gloss of Coating Surfaces.

Reflective sheen is the specular gloss value, or the degree of gloss reflected from a surface, at specified angles of illumination. It is measured by a gloss meter in accordance to ASTM D523-08, Standard Test Method for Specular Gloss.

Liquid densifiers, include an aqueous solution of silicone dioxide (i.e. silica or SiO2) dissolved in a hydroxide. The hydroxide can be either sodium silicate, potassium silicate, or an alkalis solution of colloidal silicates or silica. These hydroxides have the same chemistry, varying only by the alkali used for solubility of the SiO2. Liquid densifiers penetrate into the concrete surface and react with the calcium hydroxide to provide a permanent chemical reaction that hardens and densifies the wear surface of concrete’s cementitious portion.

A sealer is defined in ASTM D16, Standard Terminology for Paint, Related Coatings, Materials, and Applications, as a liquid composition to prevent excessive absorption of finishing coats into porous surfaces; it is also a composition to prevent bleeding.

A sealer-semi-impregnating stain protection is a film-forming material that penetrates into the polished and densified concrete, leaving a protective surface film of less than 12.7 µm (0.5 mils) which meets the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requirements for slip resistance as tested by ASTM D20471, Standard Test Method for Static Coefficient of Friction of Polish-Coated Flooring Surfaces as Measured by the James Machine, and stain resistance of ASTM D13082, Standard Test Method for Effect of Household Chemicals on Clear and Pigmented Organic Finishes.

Sealer-impregnating stain protection is a non-film-forming, stain- and food-resistant, penetrating sealer designed to be applied to densified and polished concrete. Material must meet the requirements of OSHA for slip resistance as tested by ASTM D20471, and stain resistance of ASTM D13082.

![A metal inlay within polished concrete is at the entrance to the second floor service drive of this car dealership. [CREDIT] Photo © Chris Rains, Ardor Solutions](http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Metal-inlay-1000x750.jpg)

![The car dealership floor was polished to meet a Level 3 finished gloss. [CREDIT] Photo © Chris Rains, Ardor Solutions](http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Dealership2-1000x750.jpg)

CPAA position papers

CPAA also released six position papers to expand their definitions and guidelines. This initial release of position papers includes documents that elaborate on key polishing definitions including:

- polished concrete;

- bonded abrasive polished concrete;

- burnished polished concrete;

- hybrid polished concrete;

- surface-coated concrete; and

- slip-resistance criteria for bonded abrasive polished concrete.

Each of the six standalone documents discusses the state of the industry on its respective topic, and puts forth the association’s position and proposed specifications.3

Conclusion

With attributes addressing the needs of various owners from the economic to the aesthetic, polished concrete has quickly gained popularity. As it goes from being a niche product to a commonly specified finish material, however, the development of a set of common standards is imperative. CPAA is working with industry professionals to fill this need by establishing agreed upon definitions, guidelines, and specifications. Having these in place will ensure designers and specifiers are using a common vocabulary and will provide them with a high degree of certainty regarding their finished product.

Notes

1 For a list of these terms and definitions visit www.concretepolishingassociation.com/glossary.php. CPAA’s website is also a resource for specifications and guidelines that have been developed with the input of manufacturers, architects, general contractors, and polishing contractors. Its specifications page, which is now home to the CPAA position papers, includes a photo gallery of examples of CPAA polished concrete classifications. (back to top)

2 See Note 1. (back to top)

3 For more information and to download the position papers, visit www.concretepolishingassociation.com/specifications.php. (back to top)

Kristin Dispenza, CSI, has more than 20 years of experience writing for industry publications and is an architecture/engineering/construction (AEC) editorial specialist at Constructive Communication Inc. She holds a bachelor of science degree from Ohio State University’s College of Engineering/School of Architecture. Dispenza can be reached by e-mail at kdispenza@constructivecommunication.com.

Kristin, this was an interesting article about polished concrete. I had no idea that it was becoming a lot more common in retail and residential settings. My husband has been wanting to polish the concrete in the garage. I must admit, it does look nice in the pictures. I wonder if it would turn out that nice in our garage.

Emily Smith | http://reflective-crete.com