by Laurie Wells, BES (Arch.), MA, RSW

Stone buildings, especially cathedrals, are meant to last for generations. Unfortunately, the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Albany, New York, experienced severe failures from its earliest years.

Well before the groundbreaking ceremony, the first suggestion of stone quality issues was in correspondence between the project architect, Patrick Charles Keely, and Bishop John McCloskey in 1848. The architect had specified Palisades sandstone, but an offer to supply a brown sandstone from a new quarry in Connecticut promised to save $40,000—a substantial figure, given the total project cost of $250,000. The main body of the church was completed in 1852, with the towers following in 1862 and 1888, and finally the sacristy in 1892. This article focuses on some of the challenges of this project that were specific to working with dimensional-cut sandstone.

The availability of suitable matching materials in usable dimensions on a timely basis are key elements of the building process. The long-term success of any stone assembly is the durability of the finished product. This case study explains some of the original mistakes that led to building envelope failures, and then highlights the restoration approach taken to rectify those errors.

Geology and production

Before discussing the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception project, it is important to understand the material involved. Brownstone is a sedimentary rock—a sandstone with its namesake hue.

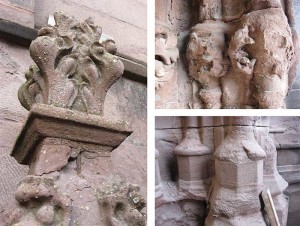

Sandstones are coarse-grained and are composed principally of quartz. The grains of sand are held together with a binding material composed of silica, calcium carbonate, or iron oxide. The addition of hematite creates the red or brown color. The stone’s quartz content makes it resistant to acid and abrasion. Compared with denser stones, such as granite, sandstones are relatively easy to cut and shape, making them ideal for decorative sculpture.

In the Early Jurassic period, approximately 200 million years ago, reddish-brown sandstone was deposited in the valleys along the Eastern Seaboard from Nova Scotia to North Carolina. Heavy downpours resulted in streams carrying eroded Ordovician gneisses and schists from the highlands into the fault valleys where the sediments accumulated in large alluvial fans. Coarser grains were deposited at the edge of the stream or lake, and finer sand, silt and mud accumulated near the center of the basins. As years pass, layers of sediment are deposited.

Portland brownstone is a type of coarse sandstone (i.e. feldspathic arenite), with feldspar content as high as 65 percent. Quartz and mica comprise most of the remainder of the rock, with albite cementing the sand grains. The red color is due to iron oxides and hematite. It is laid down in layers over millions of years and is compressed by the overlying earth. Typically, the strata are near horizontal. This orientation is called ‘natural bedding’ and, for most applications, is the preferred direction for the grain to be installed in a building as it is the most durable and least likely to fail.

However, as a building material, sandstone was commonly face-bedded, where the orientation of the strata was turned vertically and parallel to the wall line. This was likely due to the ease of cutting stone parallel to the grain, and to ‘bed-height’ limitations of the available stone. The term ‘bed height’ refers to the vertical distance of useful stone between layers of weak or soft sediments such as clay. Color and texture are also more uniform when face bedding is used.

During the peak of the production in the late 1880s, more than 1500 workers were employed by the brownstone quarries in Connecticut, which operated eight months of the year. Demand exceeded supply, and quarrying continued below the natural waterline. Saturated stones were routinely cut and sent to building sites without sufficient time to ‘season.’ (This comes from Wikipedia’s article on portland brownstone quarries.) The process of seasoning is simply allowing the stone to gradually dry out—this usually takes 12 months or more. Wet stones shipped late in the year are more than likely to fail due to frost damage. The weakest bedding planes separate and the stone disintegrates.