by Nick Brown, CEPE

As the most viewable buildings of their era still standing, the California Missions are not only state history made corporeal, but also one of the major reasons stucco is so common in the Southwest.

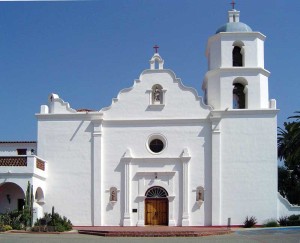

These 21 sites are rooted in Spanish, Moorish, and Mexican traditions, but many argue they represent a unique architectural style all their own. Plaster products were widely used in the Missions, and provide the stucco industry with its most relevant historical reference point. From the first Mission in San Diego in 1769 to the final one begun in 1823 north of San Francisco, the network of Spanish Missions did more to create the stucco industry than any other factor.

The Missions all started humbly, as these were frontier outposts. They worked with what was available—adobe, ladrillo bricks, and stone:

The first temporary quarters, hastily built, were little better than brush huts with grass-thatched roofs… The second structure at most of the missions was of adobe… As soon, however, as a mission was strong and prosperous, the pride of the padre usually extended to an ambition to build a church in more lasting material, hence stone or burned brick were employed. (E. Engenhoff, Fabricas [Sacramento: California Division of Natural Resources, Division of Mines, 1952], 181, as observed by Eugene Duflot de Mofras during his visit in 1840-42.)

As through the course of human history, once the Missions became prosperous, they were plastered. These churches had exterior plaster of lime-and-sand stucco, following the Roman formula of three parts clean, washed sand to one part burned lime, slaked with water. (See E. Kimbro and J. Costello’s book, The California Missions, published in 2009 by the Getty Conservation Institute.) Incredibly, the Mission construction projects drew from Roman records of building techniques written 17 centuries earlier, notably Vitruvius’s De architectura, as evidenced by books found in several Mission libraries.

Mission walls and ceilings

Together with clay roof tiles, the plaster served a vital function—protecting the underlying adobe blocks, ladrillo bricks, and stone units in the walls from moisture. When roofed, plastered, and protected from groundwater, the durable adobe walls provided effective insulation, but their soft surfaces did not lend themselves to decorative relief. A lime-based whitewash served as the final wall surface, additional protection from the weather, and an attractive finish.

Photograph © Geographer, Wikipedia. Photo licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-1.0. Generic

Mission compounds were mixes of adobe blocks with lime wash, structures of adobe and kiln-fired ladrillo bricks, and stone. The Mission’s prosperity at the time of construction determined the materials, along with the function of the building. For example, important structures like the church and convent tended to have a final plaster made of lime, which produced a hard and durable finish.

Ladrillos provided improved weather resistance and sharper lines not possible with adobe; they were widely used at Missions San Luis Rey (Oceanside), San Antonio (Monterey County), and San Diego. Prominent stone churches were built at Mission Santa Barbara, San Gabriel, and the now-ruined San Juan Capistrano. Nothing made a padre prouder than building a stone church clad in white plaster.

Interior wall decoration

While exterior walls were left simple and bare, interior walls were extensively decorated. Where Mission jobsites could not use expensive wood and stone features, they often painted them on the walls. ‘Dado’ wainscots were common, as were painted cornices at the tops of the walls. Traditional fresco painting was rare in Alta California, identified only recently at the Royal Presidio Chapel in Monterey. Executed on wet plaster, this technique allowed the paint to bond with the wall, resulting in a more durable finish.

Many of the colorful decorations used on Mission interiors were later covered due to a desire to dissociate with the buildings’ Catholic and Hispanic heritages. Some of the buildings were redecorated according to British Victorian taste, both literally and figuratively ‘whitewashed.’ Many other painted decorations were covered in wood paneling, or damaged by years of neglect. (Many of these decorations only survive today because of a New Deal-era survey of American art called the Index of American Design. Now housed at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., it contains the full spectrum of American art up to the 1930s, and included many California Mission wall decorations that would not have otherwise survived. Visit www.nga.gov/collection/iad/index.shtm and select “Folk Arts of the Spanish Southwest.” Mission San Miguel, near Paso Robles, is the only surviving completely original interior.)