Failures: What if the coating is not the weakest link?

Sometimes, the coating system may perform appropriately but be compromised by other materials in the architectural assembly.

This industrial building in the Midwest was constructed in 1945. In 2006, it was adapted for reuse as apartments. As part of the renovation, the exposed structural concrete facade was coated with an acrylic elastomeric coating. As early as 2010, the coating was observed to be peeling from the facade.

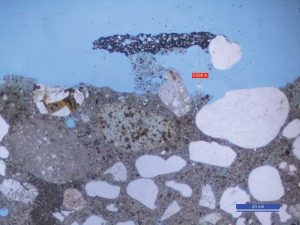

Upon detailed investigation and testing, the coating layers were found to be well bonded to one another but the adhesion to the substrate was poor. At all test locations, as well as at locations of blistered and peeling coating, concrete material was present on the reverse face of the detached coating (Figures 1 and 2). Based on this observation during study of the coating, the project scope expanded to examine the concrete substrate.

When examined petrographically, the concrete was found to have a very thin layer at the surface that had been leached of calcium and cement hydration products. At this thin layer, the cementitious hydration products that are responsible for giving concrete strength were no longer present, and the resulting layer of concrete was weak, porous, and friable. After measuring the thickness of the leached surface layer, it was found to be superficial, measuring approximately 0.635 mm (0.025 in.). Below the surface layer, the concrete was observed to be intact, with no leaching of calcium and hydration products. The weak surface layer is not a suitable substrate for the coating system. Removal of all areas of coating, followed by surface preparation to remove the weak concrete layer and recoating is now recommended.

The exact cause of the leached surface layer is not certain. It may be the result of natural weathering from acidic rain in this urban location, during the six decades prior to the renovation when the concrete facade was uncoated. However, given the similar deterioration of concrete observed in both sheltered and highly exposed facade locations, a more likely explanation may be the use of strongly acidic cleaners, followed by inadequate rinsing and neutralization, prior to application of the coating. Regardless of the exact cause, this failure points to the importance of understanding the substrate condition prior to coating application. Once the condition is known, proper surface preparation techniques can be specified.

Authors

Kenneth Itle, AIA, is an architect and associate principal with Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates (WJE) in Northbrook, Illinois, specializing in historic preservation. He can be reached at kitle@wje.com.

Kenneth Itle, AIA, is an architect and associate principal with Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates (WJE) in Northbrook, Illinois, specializing in historic preservation. He can be reached at kitle@wje.com.

Daniela Mauro is a concrete petrographer and senior associate with Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates (WJE) in Northbrook, Illinois, specializing in the investigation, evaluation, and characterization of construction materials. She can be reached at dmauro@wje.com.

Daniela Mauro is a concrete petrographer and senior associate with Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates (WJE) in Northbrook, Illinois, specializing in the investigation, evaluation, and characterization of construction materials. She can be reached at dmauro@wje.com.

The opinions expressed in Failures are based on the authors’ experiences and do not necessarily reflect that of The Construction Specifier or CSI.