By Kristina Abrams, AIA, LEED AP, CDT, CCS, Chris Bennett, CSC, iSCS, CDT, Bill DuBois, CSI, CCS, AIA, Melody Fontenot, AIA, CSI, CCCA, CCS, Kathryn Marek, AIA, CSI, CCCA, NCARB, SCIP, Keith Robinson, RSW, FCSC, FCSI, LEED AP, Ryan Stoltz, P.E., LEED AP, Vivian Volz, CSI, AIA, LEED AP, SCIP

After years of grappling with client callbacks, legal disputes, and financial losses from poor polished concrete installations, the industry has reached a breaking point: prohibit polished concrete. The cycle of repeated failures can no longer continue, prompting the urgent question—what now?

Owners and design teams are not protected by today’s inadequate and vague polished concrete specifications. From floors failing before substantial completion to skyrocketing change orders for never-ending densifier applications to the billions lost through delayed schedules, legal disputes, and contingency hemorrhaging, enough is enough.

What was once promised as a durable, low-maintenance flooring solution has been replaced by a patchwork of temporary sealers, densifiers, and polyureas—products that often require reinstallation almost immediately after application. Despite calls for clarity in specification language with accurate descriptions of work results, the definition of polished concrete has broadened to accommodate any floor finish that produces a shine. The industry urgently needs a specification framework that is measurable, verifiable, and defensible.

Without a quantifiable specification to convey contract requirements, project teams will continue to be handed polished concrete floors that are ripe for change orders and expensive to maintain. Contractors and design teams will continue to pay out contingencies without understanding what went wrong and how to protect themselves in the future. Thus, there is a need for a new solution to achieve a more reliable result that exceeds expectations. Building on straightforward material testing and proven project successes, the industry is making significant strides toward developing accountable language and precise definitions that can be universally specified to address concrete floor challenges. The focus has shifted to demanding results—quantifiable, repeatable, and validated outcomes through physical testing of the finished product delivered to the client.

A new MasterFormat number and title are being proposed to establish a common language and eliminate the misinterpretations that led to the current challenges: 03 35 44–Refined Concrete Finishing. The remainder of this article will detail the key elements of the proposed new specification, highlighting significant differences and improvements over previous polished concrete sections. It will also examine suppliers’ confusing and conflicting language, contributing to the misunderstandings and missteps that brought the industry to this point.

The polished concrete problem

The design industry has struggled with polished concrete for years. Contradictory weak specification language has left owners and design teams to simplify their aesthetic preferences based on photo representations and rely on marketing information about durability and low maintenance without proof. Inevitably, projects continue to have mixed results, where owners must accept problematic floors because they cannot be rejected contractually.

The language used to describe polished concrete lacks precision and clarity, making it difficult for owners to understand what they are purchasing, tough for designers to specify, and unclear for contractors to understand what they are required to build. Terms such as “high gloss,” “reflective,” “sustainable,” and “durable” can be highly subjective and used differently by manufacturers. This ambiguity can lead to misinformed choices based on marketing rather than factual performance characteristics.

The categorization of polished concrete into various levels of sheen can confuse even veteran professionals, as the criteria is broad, and producer results can vary widely. The Concrete Polishing Council (CPC) provides four appearance levels using Distinctness of Image (DOI) gloss with Level 1: flat, Level 2: satin, Level 3: polished, and Level 4: highly polished with gloss and reflectivity as the measurement guideline. These levels, from CPC’s Exposed/Polished Concrete Exposure Chart, are defined by image distinction, gloss value, and haze—characteristics based on reflection and lighting, not actual physical characteristics of the concrete.

There are countless floor finishes (e.g. grind and seals, burnished polish concrete, etc.) and many ways to achieve gloss levels. When the path to the work result is only gloss, contractors will seek out the most economical way to fit the definition of polished concrete and meet the required DOI gloss level. Despite the design team’s best efforts in using the specification guidelines provided by manufacturers, results often disappoint. Sometimes, that same spec language is used to defend the undesired outcome—rather than serving their intended purpose to ensure the desired quality results for the owner.

What is polished concrete, exactly?

According to CPC, polished concrete is “the act of changing a concrete floor surface, with or without aggregate exposure, to achieve a specified level of finished gloss.” The definition further states there are different types of polished concrete: “Bonded Abrasive Polished Concrete, Burnished Polished Concrete, or Hybrid Polished Concrete.”

CPC defines bonded abrasive polished concrete as “the multi-step operation of mechanically grinding, honing, and polishing a concrete floor surface with bonded abrasives to cut a concrete floor… to achieve a specified level of CPC-defined finished gloss.” Burnished polished concrete is defined by CPC as “the multi-step operation of mechanical friction-rubbing a concrete floor surface with or without waxes or resins to achieve a specified level of CPC defined finished gloss.” By definition, the burnished version of polished concrete can include coating the floor with waxes and resins. The CPC notes that this “yields a less durable finish and requires more maintenance than bonded abrasive polished concrete.”

Hybrid polished concrete combines burnished polished concrete, bonded abrasive concrete, or anything in between that attempts “to achieve the specified level of CPC-defined finished gloss.”

The emphasis on shine

This emphasis on achieving gloss (specular gloss, DOI gloss, etc.) has led to practices prioritizing aesthetic qualities over functional durability. The pursuit of shine in polished concrete usually involves the use of chemical sealers, sometimes called “guards,” latex, acrylic, and various grouts, as well as solid epoxy tooling, which coats the floor as it is superheated and resin is transferred via friction rubbing to fill and hide scratches and imperfections with a thin shiny coating rather than correct the concrete surface. Whether a floor is refined without topical treatments or coated with resins and sealers, CPC classifies all these floor types as “polished concrete” if they achieve gloss—sometimes.

The glossary page of the CPC includes a definition for surface-coated concrete, indicating that “surface-coated concrete (waxes and resins) does not conform to the definition of polished concrete. It is the operation of applying a film-forming coating to a concrete floor surface to achieve a specified level of finished gloss.” In other words, the defined end result of surface-coated concrete is essentially the same as burnished polished concrete. By definition, both aim to achieve a level of gloss. This means substitutions involving any cheap grind and seal or temporary burnished film-forming material contractually meet the design intent—despite not meeting the design intent. How can a specifier reject a work result that is both allowed and not allowed?

While concrete is inherently durable, an overly aggressive dry polishing process often compromises the material’s integrity by destroying the finished slab’s most durable top “skin,” making it more susceptible to staining, scratching, and general wear. This degradation necessitates an initial grout coat and more frequent lifecycle refinishing and maintenance, contradicting initial claims of a problem-free floor. Thus, while the polished surface may initially appear appealing and shiny, its long-term viability (compounded by frequent coating applications) is questionable.

Concrete refining

The refining process is guided by initial measurements of average roughness (Ra) and Mohs hardness readings, which will be discussed in detail shortly. Refining includes wet mechanical refinement with power trowels or grinding equipment and chemical components that react with cement particles and free lime to stabilize and reshape the surface. Cement binds to form concrete. The unhydrated cement in the concrete tailings gets reincorporated to strengthen the surface concrete, and the newly exposed cementitious content has the opportunity to hydrate and strengthen the surface while it is in a malleable state, reworked back into itself, and then refined to provide an improved denser surface. Many professionals may be unaware that the top surface of a concrete slab can be reworked and refined after initial hardening, making refined concrete appropriate for a slab that is 40 years old or brand new.

The top 19 to 25 mm (0.75 to 1 in.) of a concrete slab is most susceptible to physical damage and the effects of nature. Decreased moisture content (MC) and lowered relative humidity (RH) from poor external curing practices also impact the durability of the top layer. This can significantly reduce the surface strength of concrete when the humidity drops below 80 percent as the hydration of the cement particles nearly stops below this level and does not restart when RH increases. The concrete refining process provides immense value and redefines the finishing and maintenance processes to help answer many of these issues.

A refined slab exhibits the same aesthetic capabilities of polished concrete (aggregate exposure levels, color, and DOI gloss) without coatings, sealers, and resinous grouts common with polished concrete. In fact, the concrete itself becomes the grout during the refinement process, addressing pop-outs, cracks, and other small voids. Refined concrete creates a measurable, monolithic floor slab with its surface integrity intact.

“Unlike polished concrete, which may be a mix of resinous and cementitious materials, the single concrete matrix of refined concrete will accept color, react with humidity, and respond to its environment in more predictable and aesthetically pleasing ways,” says Chris Bishop, president of the National Concrete Refinement Institute (NCRI).

Refining concrete eliminates topical impurities that have become standard with most “polished concrete” methodologies and results in more flexibility with the final finish, such as staining, dyeing, or even maintaining a truly refined concrete surface, but for much less money.

Refined concrete benchmarks

Physical readings from the concrete itself quantify performance benchmarks for refined concrete. Aesthetic benchmarks from the coating industry (DOI gloss, lumen levels, etc.) can also be used. Still, physical benchmarks ensure resilience, durability, simple maintenance, and a long service life that owners associate with exposed concrete floors. The three most important physical benchmarks are Ra, Mohs hardness, and dynamic coefficient of friction (DCOF).

Average roughness (Ra)

These microsurface benchmarks for refined concrete are measured in microinches (μin) or micrometers (μm) per the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) B46.1-2019 (R2019), Standard for Surface Texture (Surface Roughness, Waviness, and Lay). This standard provides a practical method for measuring Ra on a surface.

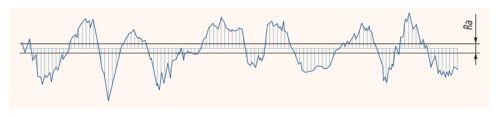

Scott Langerman, P.E., of Langerman Engineering says, “Measuring the roughness average (Ra) provides input for concrete surface refinement. The Ra test is performed with equipment (profilometers) that measure the roughness/smoothness to the micro-inch. Data are then used to determine steps for the initial grinding process, minimizing surface micro fractures and maximizing refinement. After refinement is done, the Ra test is then performed again to determine that project specifications have been achieved.”

Ra notes

- Ra is the numerical average of the total peaks and valleys across the length of a tested surface. It is also sometimes called the Center Line Average (CLA).

- A minimum specification benchmark for placement and finishing new concrete should be 2.54μm (100μin) or less.

- Minimum Ra benchmarks for refined concrete may include matte finish: 0.76μm [30μin] or less; semigloss: 0.50μm [20μin] or less; glossy: 0.254μm [10μin] or less. A tolerance of +/- 0.127μm [5μin] is acceptable in most cases.

- The NCRI provides education to architects and engineers and certification courses on surface measurement and refinement to installers.

Mohs

The Mohs test is a simple verification that can be performed on hardened concrete to help determine when the slab is ready to receive installation of a refined concrete finish and set minimum contractual benchmarks for the completed concrete surface. The ASTM standards referencing the Mohs hardness test are ASTM C1790-16 and ASTM C1895-20. These standards outline procedures for determining the hardness of a material using a scratch test, such as the Mohs hardness scale. While the Mohs test is a qualitative method originally devised in the early 19th century, these standards incorporate the Mohs principle and adapt it for specific industrial applications, including concrete and other materials that can be used to design and defend a minimum expectation of abrasion resistance.

Mohs notes

- The Mohs scale ranks materials based on their ability to scratch softer materials.

- It is a comparative scale, ranging from 1 (talc) to 10 (diamond).

- ASTM C1790-16 and ASTM C1895-20 emphasize controlled testing procedures to ensure reliability and repeatability.

- A minimum specification benchmark for a refined floor can be safely set at 7Mohs.

- 7Mohs is roughly equivalent to quartz. Natural concrete can achieve up to 8 and 9Mohs.

Dynamic coefficient of friction (DCOF)

Some film-forming coatings, such as epoxy and acrylic systems, can achieve a high gloss when burnished, creating a refined look to the floor. However, they also create a surface film that poses challenges for maintaining adequate traction and, consequently, a higher coefficient of friction (COF). With slips, trips, and falls constituting a significant percentage of workplace injuries, including 67 percent occurring on level surfaces, achieving and maintaining an appropriate COF is critical for user safety. DCOF is a measurement of the floor, similar to Ra and Mohs.

DCOF notes

- DCOF measures the resistance between two surfaces in relative motion.

- DCOF measures a surface already in motion, as opposed to the static coefficient of friction (SCOF), which measures resistance before motion begins (i.e. lawsuits and injuries from people slipping and falling are more directly related to DCOF, not static COF.).

- The NFSI is a resource that provides training and third-party testing and actively supports standards such as B101.1, B101.3, and B101.4.

- ANSI B101.4 includes updated metrics for bare-foot travel on hard surfaces.

Final set

While polished concrete can offer certain aesthetic and practical advantages, focusing on surface gloss or shine rather than lasting durability compromises the end result. The impacts of outdated topical treatments and resinous tooling used in current polishing practices, coupled with the lack of clear definitions and standards, present significant challenges for design teams and contractors. Clarity is power, but the confusing language surrounding polished concrete continues to breed errors, change orders, and deep frustration.

As the construction industry progresses, it is essential to emphasize transparency, precision, and authentic quality in flooring solutions, moving away from materials and methods that favor short-term aesthetics and financial gain over long-lasting performance and value.

It is time to move beyond the confusion surrounding polished concrete and set new standards by introducing “refined concrete” as a long-overdue solution. Measuring light reflected off a floor is not the same as assessing the quality and performance of the floor itself.

Physical benchmarks addressing the performance of the concrete must more effectively anchor the design intent to deliver truly durable and sustainable finished concrete floors. Section 03 35 44–Refined Concrete Finishing is a step toward a more “concrete” exposed finish outcome. The next time a client considers a polished concrete floor, look closer at their expectations. Suppose their vision extends beyond mere shine to include durability, sustainability, and a maintenance schedule that avoids decades of reliance on petrochemical veneers. In that case, they may actually be looking for refined concrete.

Resources

To explore the relationship between friction coefficient and surface roughness of stone and ceramic floors, refer to this detailed study on ResearchGate, researchgate.net/publication/355344967_Relationship_between_Friction_Coefficient_and_Surface_Roughness_of_Stone_and_Ceramic_Floors

For insights into communicating effectively with project teams and redefining concrete language, visit Construction Canada’s article, constructioncanada.net/changing-the-language-of-concrete-communicating-clearly-with-the-project-team

To learn more about the ANSI/NFSI B101.2-2012 standard for walking surface safety, check out this comprehensive overview on the ANSI Webstore, webstore.ansi.org/standards/nfsi/ansinfsib1012012-1443377?gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAiA9IC6BhA3EiwAsbltOMdpSLzOzGmvpNFftUAYOxdihJoO1Mk9thL_7OhTGF-s2jOU-B-UDRoCQHIQAvD_BwE

For information on advancing concrete refinement practices, explore the National Concrete Refinement Institute’s (NCRI) website, theNCRI.com.

To ensure safe walking surfaces on exposed concrete, consider reading this article from The Construction Specifier, constructionspecifier.com/ensuring-safe-walking-surfaces-exposed-concrete

For a discussion on polished concrete that goes beyond aesthetics, delve into this feature in The Construction Specifier, constructionspecifier.com/polished-concrete-not-just-shiny

To clarify terminology related to concrete polishing, consult the American Society of Concrete Contractors’ (ASCC) glossary of terms, ascconline.org/polishing/glossary

Authors’ note: The authors extend their gratitude to Sherry Harbaugh, John Guill, Rae Taylor, Paul Gerber, Alma Jauregui, Brian Heather, Mitch Miller, Michael Thrailkill, Thomas Robinson, Toru Narita, Matt Ferguson, Jennie Perlmutter, Doug Robertson, Jim Wilson, Michael Zhao, Norm Doergess, Gloria Barrera, Kevin Hafer, Luis Adan, Anne Whitacre, Peter Roy, Bill Nelson, and many others. Their shared stories, unique perspectives, and invaluable contributions have significantly shaped the journey that led to this point.

Authors

Kristina Abrams, AIA, iSCS, LEED AP, CDT, CCS, is an architect with more than 20 years of experience collaborating with design teams nationwide. As director of specifications at O’Connell Robertson, she focuses on establishing clear project terminology early in design to strengthen communication and improve contract documents. Abrams is passionate about bridging the gap between drawing and specification intent design intent.

Chris Bennett, CSC, iSCS, CDT, is a concrete consultant in Portland, Ore. He has trained thousands of architects, engineers, and contractors on how to produce better results and reduce risk in concrete. His firm, Bennett Build, leads project teams in lowering the economic and environmental costs of designing and implementing stronger concrete systems.

Bill DuBois, AIA, CSI, CCS, is an architect who is passionate about working with the entire construction project team, which includes owners, designers, constructors, and suppliers. DuBois strives to improve the decision-making processes necessary for efficiently implementing powerful design solutions and creating construction specifications to reduce risk and maximize value.

Melody Fontenot, AIA, CSI, CCCA, CCS, iSCS, SCIP, is a senior specification writer with Conspectus Inc., based in Portland, Ore. A licensed architect with more than 20 years of experience, she specializes in project management, construction documents, and contract administration. Passionate about product research and spec knowledge, she strives to improve communication across the architecture, engineering, construction, and owner (AECO) industry.

Kathryn Marek, AIA, CSI, CCCA, NCARB, SCIP is a specifier and an architect. She is the principal at KM Architectural Consulting and the current president of SCIP.

Keith Robinson, RSW, FCSC, FCSI, is an architect and specifier in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. Robinson also instructs courses for the University of Alberta, acts as an advisor to several construction groups, and sits on many standards review committees for ASTM and the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA).

Ryan Stoltz, P.E., iSCS, LEED AP is a licensed structural engineer, LEED accredited professional, and associate principal at Structures, a North American engineering firm in Austin, Texas.

Vivian Volz, AIA, CSI, LEED AP, SCIP, is an independent specifier for commercial, public, and multifamily projects in California and beyond. Volz has served as a local and national leader in the Construction Specifications Institute (CSI) and is SCIP’s immediate past president.

Key Takeaways

The polished concrete industry has long struggled with vague specifications, disappointing outcomes, and high maintenance demands. Floors often fail to meet promised durability and sustainability, relying on temporary treatments and resinous coatings. The proposed solution, “refined concrete,” emphasizes measurable benchmarks like Ra, Mohs, and DCOF to ensure lasting performance. Unlike polished concrete, refined concrete uses a single concrete matrix to deliver durability, sustainability, and low maintenance without relying on petrochemical-based veneers. A new MasterFormat section, 03 35 44–Refined Concrete Finishing, aims to establish clarity and accountability. This approach prioritizes functional quality over superficial shine, providing a more durable and predictable result for clients seeking sustainable flooring solutions.

I need a sealed concrete floor at 800 grit with an epoxy sealer. This was in a recent finish schedule for a project. What did they want?