By Matthew Ridgway, P.E.

As building codes and standards evolve, the demand for airtight, environmentally friendly building enclosures increases among building owners, insurers, and design professionals. These stricter regulations aim to reduce energy consumption and enhance overall building performance, making air barriers a key element in today’s construction practices.

Air barriers are essential for maintaining the integrity and performance of building enclosures. By preventing uncontrolled air movement between conditioned and unconditioned spaces, they help regulate indoor temperatures, control moisture, and improve energy efficiency. When designed and installed correctly, air barriers contribute to the long-term durability of a building. However, if an air barrier fails, it can lead to significant problems in both new and existing buildings, including reduced insulation effectiveness, resulting in higher energy bills and moisture intrusion, potentially allowing for the development of toxic mold, and even premature failure of building components.

Role of air barriers

Modern building enclosures are designed to maintain a stable indoor climate by separating conditioned spaces from external or semi-conditioned areas. While their primary function is to control air at a pressure boundary, air barriers can also help control water, vapor, and radiation, depending on the materials used and how they function in combination with other building components. All of these factors, along with thermal resistance, define the performance of a building enclosure assembly.

Though there is a historical context for controlling air infiltration through the building enclosure, historical methods and requirements have been ad hoc and mostly material-based until the modern era of construction. Drafty building enclosure assemblies of past eras contributed to higher energy use to keep occupants comfortable but have also played a role in maintaining the long-term durability of a building by helping to address issues related to poor water and vapor control (i.e. drafty buildings dry more readily).

Within the AEC industry, research focuses on predicting and quantifying the impact of air leakage. Using energy models and computational fluid dynamics, experts can analyze air distribution and how air leaks affect energy consumption at the building, assembly, and individual component levels.

Empirical evidence from physical testing and energy bill analysis confirms that reducing air leakage through a building enclosure can save on fuel used to air condition a building. As buildings become more airtight to save on these fuel costs, reducing air leakage can prevent other potential building performance issues arising from uncontrolled airflow in an otherwise high-performing building.

Improving building enclosure performance

While energy efficiency might initially suggest well-insulated walls and efficient HVAC systems, controlling air leakage can be just as critical. Uncontrolled air movement through penetrations in the building enclosure can increase energy costs as HVAC systems work harder to condition the air. At a building level, uncontrolled air leakage may also lead to issues with stack effect, which can have a compounding impact on building performance. Also defined as the “chimney effect,” stack effect is the natural propensity for hot air to rise. In multistory buildings, especially in winter, cold air rushes into lower levels while warm air is exhausted through the top of the building.

A continuous air barrier system also protects the building structure by reducing the risk of localized condensation or moisture accumulation. An air barrier that also performs as a weather barrier, or an air weather barrier (AWB), acts as a shield and stabilizer, protecting the building enclosure from external elements while optimizing internal energy performance.

Financial benefits

One driving force behind the increasing demand for high-performing and airtight buildings is the combined efforts of industry and government to reduce energy consumption. While carbon reduction from embodied energy is an environmental benefit, for this purpose, the focus is solely on the fuel costs associated with conditioning buildings.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, residential and commercial buildings account for approximately 27.6 percent of the total energy consumption in the United States. Space heating is the largest single energy end-use in commercial buildings, consuming 32 percent of energy, followed by ventilation at 10 percent.

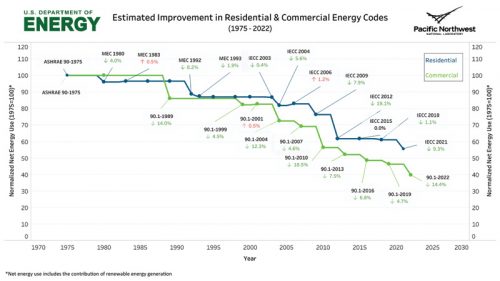

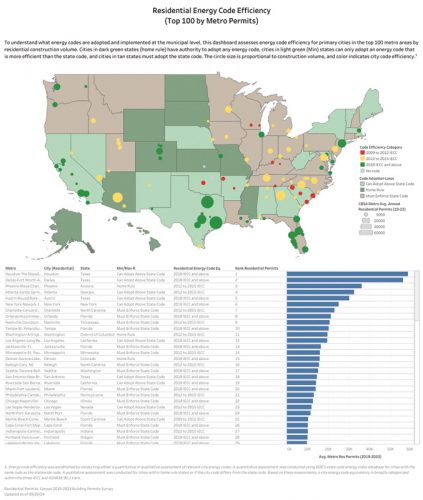

The ongoing evolution of building codes has continued to drive energy reductions. By implementing stricter energy efficiency standards, these codes have incentivized the construction of higher-performing buildings.

A high-performance building is one that optimizes building performance to ensure long-term durability and resilience. Such attributes including energy efficiency, lifecycle and serviceability enhancements, IAQ, sustainability targets, and reductions in embodied carbon.

These high-performance buildings offer several advantages, including a longer lifespan and reduced energy demands. Savvy building owners recognize that airtight buildings minimize the financial risks of future repairs or major renovations. Additionally, properly constructed air barriers result in lower operating costs. In certain regions, high-performing buildings have become a marketing tool to enhance property value and tenant occupancy.

Testing, design, and regulatory compliance

Several ASTM tests are commonly used in the construction industry to ensure the performance and durability of air barriers. Quantitative and qualitative methods are used during testing to assess how well the system works.

Quantitative testing measures the air leakage rate, showing how effectively the air barrier controls airflow through the building enclosure. Qualitative methods help identify specific areas where air leakage might occur, allowing for targeted repairs before construction is completed.

Quantitative methods include:

- ASTM E1827, Standard Test Methods for Determining Airtightness of Buildings Using an Orifice Blower Door. This method evaluates a building’s airtightness by creating a pressure differential with a blower door. It offers two options: a single-point test (usually at 50 Pa [1 psf] for dwelling units) and a two-point test (using two pressure levels) to measure air leakage. Commonly used in residential and commercial buildings, it helps identify air barrier weaknesses and improve energy efficiency.

- ASTM E779, Standard Test Method for Determining Air Leakage Rate by Fan Pressurization. This multi-point test uses a blower door to pressurize or depressurize a building and measure air leakage. The air leakage rate is calculated by the airflow required to maintain a pressure difference, typically 75 Pa (1.5 psf), and reported as cubic feet per minute (CFM) per square foot (sf) of building enclosure area. This method is used in new and existing buildings to assess airtightness and identify areas for improvement in the air barrier system.

- ASTM E3158, Standard Test Method for Measuring the Air Leakage Rate of a Large or Multizone Building. This method was developed from the Air Barrier Association of America’s (ABAA) Standard Method for Building Enclosure Airtightness Compliance Testing and refines the above methods.

- The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Air Leakage Test Protocol for Building Envelopes. This protocol establishes a standardized method to measure air leakage in building enclosures, particularly in military and government buildings. It combines quantitative tests such as ASTM E779 with qualitative methods such as infrared scanning and smoke tracing from ASTM E1186. Using blower doors to pressurize or depressurize buildings, it evaluates air leakage at standardized pressure levels, typically 75 Pa (1.5 psf), to ensure compliance with airtightness standards, enhancing energy efficiency and durability.

Qualitative methods include:

- STM E1186, Air Leakage Site Detection in Building Envelopes and Air Barrier Systems.

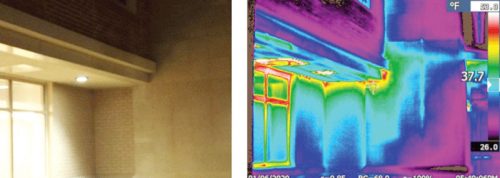

- Practice 4.2.1—Infrared Scanning with Depressurization/Pressurization. A blower door creates a pressure differential, and infrared cameras detect temperature variations, pinpointing leaks in insulation and around windows or doors.

- Practice 4.2.2—Smoke Tracer with Depressurization/Pressurization. Smoke is released near potential leak sites, and its movement reveals gaps in the air barrier system, especially around windows, doors, and utility penetrations.

- Practice 4.2.3—Airflow Measurement (Anemometers). Anemometers measure airflow at suspected leakage points during depressurization or pressurization, identifying areas with significant air leaks.

- Practice 4.2.4—Sound Detection. Low-frequency sound is generated in the building, and detectors identify leaks by picking up sound variations through the building enclosure.

- Practice 4.2.5—Tracer Gas. A tracer gas, such as sulfur hexafluoride, is released and detected to identify leaks by measuring gas concentration differences inside and outside the building.

Mock-ups are also frequently used in the pre-construction phase to confirm air barrier systems can be installed properly and perform as expected in real-world situations. Pre-construction testing is essential to check for proper adhesion of the air barrier and air leakage resistance at penetrations and transitions of air barrier assemblies, reducing the chance of issues arising during construction and after the building is occupied.

Durability across climates

Air barriers must be durable in all climates to withstand each region’s unique environmental challenges. Factors such as temperature fluctuations, humidity, wind, construction type, and exposure must be carefully considered when designing and installing air barrier systems. Climate considerations and the location of insulation in a wall assembly might dictate a need for vapor-permeable air barriers to accommodate vapor drive. Regions with harsh winds or extreme temperatures may require barriers with varying adhesive or facer properties.

When designing air barriers, consider the specific climate conditions of the region, as well as the type of construction, wall assembly, and project timeline. The chosen air barrier system must withstand the environmental conditions it will face throughout its service life. Air barriers now vary widely in chemistries and applications, including systems integrated with sheathing, fluid-applied, spray-applied, sheet-applied, and self-adhered (SA) options, each offering different advantages depending on the climate, building type and use case.

Performance characteristics such as water penetration resistance, vapor permeability, adhesion, and fire resistance are also crucial for durability. Construction practices, including the quality of installer training and regional installation preferences, significantly impact an air barrier’s success. Exposure limitations, such as UV, wind, or rain sensitivity, must be managed carefully during installation to prevent premature failure. The air barrier must also resist building movements and be designed for continuity across movement joints and transitions between other exterior wall assemblies and openings.

The design and installation of air barriers and other building enclosure systems can also influence the ‘right-sizing’ of mechanical equipment. Building energy use, influenced by climate zone-specific code guidelines and building owner decisions, directly impacts mechanical system designs. Mechanical design and energy modeling typically rely on minimum criteria defined by ASHRAE for heating and cooling degree days, which measure the average outdoor temperatures compared to a standard temperature, typically 18 C (65 F) in the United States. The 2021 version of the International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) revised its climate zone map to reflect rising average temperatures across the U.S. due to climate change and added additional requirements for air barrier assurance.

Impact of failed air barriers

Failures in air barrier systems can lead to uncontrolled air leakage, often worsened by building pressurization or depressurization. This forces HVAC systems to work harder to maintain indoor temperature set points and can have severe consequences for moisture control within the building’s components and assemblies. The amount of moisture that can enter a building due to a discontinuity in the air barrier is greater than what occurs through vapor diffusion alone. Defects in air control layers can allow moisture to accumulate within the building’s walls, resulting in several problems, including reduced effectiveness of thermal insulation, the potential for biological growth, and even structural failure within the wall assemblies.

Air leakage becomes even more problematic when there is a significant difference between indoor and outdoor temperatures. In such cases, condensation can occur when moisture within the ambient air condenses on surfaces at or below the dew point temperature. In winter, cold outdoor air infiltrates the building enclosure and causes interior surfaces to cool, which can lead to condensation of ambient interior warm, moist air. Similarly, warm, humid air can infiltrate an air-conditioned building in summer, causing condensation on cooler ambient surfaces.

Condensation, especially in areas with poor ventilation, can accelerate mold growth, material rot, and risk of structural damage. The long-term effects of air barrier failures are detrimental to both the performance and durability of the building, as well as the occupants within.

Preventing common failures

Many failed whole-building airtightness tests can be attributed to relatively simple issues that could have been addressed during the design or construction phases. Common problem areas include transitions between soffits to walls, parapet transitions to roofs, and window terminations to the air barrier. Mock-ups and testing of these transitions during construction can be worth the extra effort and cost.

Construction-related issues often stem from poor quality control or work performed out of sequence, such as making roof or wall penetrations after roofing or cladding installation, which can limit the ability to properly terminate air barriers to ducts, piping, or electrical conduits. Some of the most complex challenges in air barrier design and application are related to the interior compartmentalization of buildings. Issues such as malodor, stack effect, and condensation are among the most common problems identified during diagnostic and forensic testing of whole buildings.

Additionally, the industry still faces challenges in maintaining air barrier continuity at the sills of curtain walls, storefronts, and flanged windows. Designing an air barrier to be continuous, even with the complexities of structural and drainage requirements, is critically important but not impossible with proper coordination.

Codes and standards

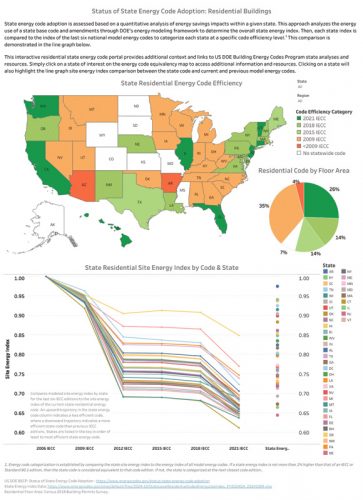

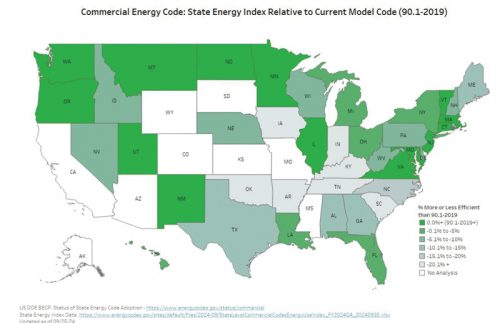

IECC and ASHRAE 90.1 standard are primarily referenced for compliance with a commercial building’s energy performance and verification. While the 2021 IECC is not yet required in all jurisdictions, it is gaining adoption, and several states and cities have implemented local codes, often referred to as “stretch” codes, which include stricter requirements for both testing and/or other prescriptive requirements to ensure airtightness of buildings.

For commercial buildings, the 2021 IECC now includes a requirement to comply with ASHRAE 90.1–2019 and requires buildings to have a posted a Thermal Envelope Certificate. This certificate must include R-values of insulation installed across the building enclosure and ducts outside-conditioned spaces of the building, U-factors and solar heat gain coefficients (SHGC) of fenestrations, and the results of any building enclosure air leakage testing performed on the building.

The 2021 IECC also requires the installation of a continuous air barrier, which must be verified by a qualified professional such as a code official, design professional, or an approved agency. A final report detailing any deficiencies and corrective actions is required. Residential requirements include the building or dwelling unit enclosures must be tested in accordance with ASTM E779, ANSI/RESNET/ICC 380, ASTM E1827, or another equivalent method approved by the code official, with air leakage not exceeding 0.0079 m3/(s x m2) [0.28 CFM/sf] at 0.2 inch w.g. (50 Pa). Similarly, commercial requirements include that the whole building thermal envelope (building enclosure) must be tested according to ASTM E779, ANSI/RESNET/ICC 380, ASTM E3158, ASTM E1827, or an equivalent method approved by the code official, with air leakage not exceeding 2.0 L/s x m2 (0.40 CFM/sf) at 0.3 inch w.g. (75 Pa).

Technological advancements

Recent technological advancements have significantly improved the design and testing capabilities of air barrier systems. Hardware and software packages, which have become more affordable, now include compatible fans, manometers, and Wi-Fi-enabled software packages. These improvements streamline the process of conducting airtightness tests and allow for real-time data collection and analysis, making it easier to assess and adjust air barrier performance.

Diagnostic tools for detecting air leakage, such as infrared scanners and smoke tracers, have also improved and become more affordable, helping identify leaks more accurately and quickly. However, there is still room for further advancements, particularly in developing higher-powered blowers to test larger buildings and reducing setup times for testing procedures.

Additionally, as air-tightness requirements improve via codes and standards, other non-compulsory programs continue to aim for even higher performing buildings. Programs such as Phius’ Passive House, and Net Zero Standards can only be achievable with improvements in energy recovery and air filtration in order to minimize the energy use required for ventilation.

Involving a consultant

Involving a qualified building enclosure consultant in the air barrier design and installation process is important due to their specialized expertise. They possess in-depth knowledge of air barrier design, materials, installation techniques, and testing procedures. They stay current with evolving building codes and regulations, guaranteeing the project complies with all requirements. Building enclosure consultants also can identify potential problem areas early on and suggest solutions that prevent costly issues later. By overseeing the construction process, they can ensure the air barrier is installed correctly and meets performance standards before code-required testing.

Conclusion

Air barrier systems offer many benefits beyond compliance with building codes. Investing in a well-designed and properly installed air barrier system can improve energy efficiency, enhance indoor comfort, protect building components, increase property value, and reduce environmental impact. Air barriers are not merely a compliance requirement but a strategic investment that can deliver long-term benefits for building owners and occupants. By prioritizing air barrier performance, project teams can ensure a building is comfortable and sustainable for years.

Author

Matthew Ridgway, P.E., is an architectural engineer with 20 years of experience specializing in building enclosure systems. As the Northeast director of Intertek’s building and construction division, Ridgway leads the building science solutions consulting group and provides technical oversight of several regional laboratories. Ridgway’s design work includes building enclosure consulting and historic restoration. His passion is investigative and forensic work which has focused on building performance issues including water intrusion, building instrumentation, air leakage and condensation analysis for modern and historic roofing, waterproofing, fenestration, and opaque walls. He has also conducted in-depth investigations into manufacturing defects of prefabricated systems. His experience in commercial and institutional project planning and repair prioritization informs his professional practice.

Key Takeaways

As building codes become more stringent, the demand for environmentally friendly, airtight buildings is increasing. The 2021 International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) and related standards are key drivers of this trend, leading to more rigorous testing standards for building enclosures and airtightness. A well-designed air barrier system must be structurally sound and durable in all climates. When an air barrier fails, it can cause serious issues such as reduced insulation effectiveness, unwanted air infiltration, mold growth, and premature failure of building components. ASTM tests play a critical role in validating the performance of air barrier systems, while the 2021 IECC has significantly impacted building codes nationwide. This has heightened the focus on energy efficiency and airtightness, making whole-building inspections and airtightness testing for new construction more common.