by Steven D. Marino

Among the many reasons architects specify glass are its beauty and versatility. In addition to offering the full spectrum of transparency, color, and high environmental performance as vision glass components, this material can be opacified in spandrels to create visual flair on building façades while hiding unsightly interior features such as hung ceilings, knee-wall areas, between-floor voids, mechanical equipment, wires, vents, and slab ends. Although glass spandrels have been popular on building façades for decades, there are technical factors design professionals must account for when specifying these assemblies.

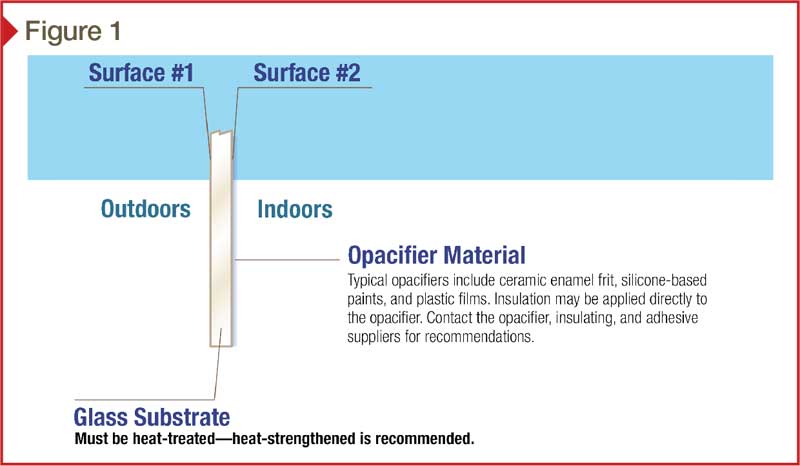

Through the application of coatings, film, or other materials to the indoor surface of a glass lite, glass spandrels block light and prevent transparency. In monolithic and insulating glass unit (IGU) spandrels—the two most common types—ceramic enamel frits, silicone-based paints, and plastic or metal films are affixed to or installed just behind the glass substrate to make it opaque.

Shadow box spandrels are a third alternative. Unlike the aforementioned conventional spandrels, these assemblies incorporate transparent glass and unite it with a separate insulating component. In most cases, this component is a rigid foil-backed material, taped to the surrounding framing system to prevent the passage of light.

Although monolithic and IGU spandrels are typically specified to enhance the building’s appearance, it is usually impossible to create a seamless color match between spandrel glass and vision glass on a façade with these types of units. However, because they can be fabricated with an almost limitless palette of opacifier colors, monolithic and IGU spandrels are ideal for complementing vision glass and other building finishes such as metal, brick, concrete, and stone.

If a strong color match between vision glass and spandrel glass is desired on a building exterior, using shadow box spandrels is recommended.

Monolithic glass spandrels

Monolithic glass spandrels are the most basic spandrel variety, consisting of a coated or uncoated glass substrate to which an opacifier is applied, as seen in Figure 1.

Images courtesy Vitro Architectural Glass

Most manufacturers recommend all glass specified for monolithic spandrels be heat-strengthened to provide the mechanical strength needed to resist wind load and thermal stresses. The inherent break pattern of heat-strengthened glass is another reason for this recommendation, as broken heat-strengthened glass is much more likely than annealed (i.e. non-heat-treated) or fully tempered glass to remain in place until it can be replaced.

Whether heat-strengthened or fully tempered, heat-treated glass products are produced in a similar fashion and using the same processing equipment. The glass is heated to approximately 650 C (1200 F), then force-cooled to create surface and edge compression. The cooling rate of the glass determines if it is heat-strengthened or fully tempered—to produce the latter, cooling is much more rapid, creating higher compression; for the former, cooling is slower, resulting in a compression lower than fully tempered glass, but higher than annealed.

As indicated in Figure 1, insulation is often used in conjunction with spandrel glass. When the insulation is to be applied directly to the opacified surface of the spandrel glass, it is important to work with a glass spandrel fabricator, as well as the adhesive and insulation suppliers, to ensure these products are compatible with the opacifying material. These suppliers can also recommend the best installation procedures for ensuring long-term performance and appearance.

Is there a way to remove the ceramic frit from spandrel glass?