Revising Lead-free Plumbing Mandates: Crucial questions for specifiers and architects

by Brad Noll

The capability to predict the future can run hot or cold, especially for specifiers and architects considering lead-free plumbing products and potential liabilities murkily pouring from a new federal law set to take effect January 2014.

The Reduction of Lead in Drinking Water Act (42 USC s. 300G–6) complements the federal Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA). It requires any pipe, plumbing fitting, or fixture providing water for human consumption to be lead-free. Specifically, the affected plumbing products must have a weighted average of no more than 0.25 percent lead content, as per NSF International/American National Standards Institute (ANSI) Standard 372, Drinking Water System Components–Lead Content.1 The previous allowable lead content level, established in 1986, was eight percent. The new law becomes effective January 4, 2014.

The U.S Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) will issue regulations associated with the implementation of the Reduction of Lead in Drinking Water Act, although no timetable has been set for the issuance of those regulations and the agency has not provided guidance related to it. Various industry groups and other interested parties have provided written comments to EPA in an effort to assist in developing these regulations.

Why lead-free?

The regulations eliminating lead from certain plumbing products follows the removal of lead from gasoline and paint. Studies have demonstrated long-term exposure to lead can pose serious health risks, particularly to children and senior citizens. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and EPA have stated there is no safe threshold for blood lead levels in young children. Further, children up to age six are most at risk because of that period’s significance for brain development.2 Adults can experience kidney damage, reproductive effects, high blood pressure, memory loss, and problems when concentrating.

Lead is a metal found in natural deposits, but rarely found in source water. It enters tap water through the corrosion of plumbing materials, typically those manufactured from brass or bronze. Due to its self-lubricating ability, lead enhances machinability in the manufacturing process and pressure tightness—regarding the latter, lead fills the voids in castings to prevent leak paths from interior to exterior surfaces.

The World Health Organization (WHO) states lead has no known biological benefit to humans.3

Implications

From a business standpoint, any product failing to meet the new federal mandate and still in inventory on the Reduction of Lead in Drinking Water Act’s effective 2014 date becomes obsolete and ineligible to sell. However, the law should guide plumbing system specifications starting this year.

From a legal standpoint, distributors, contractors, specifiers, and other professionals could be held liable for distributing products not meeting the new standards. In fact, given the way the legislation was written, some plumbing community members think end-users could also be held liable.

The new law states exemptions which include:

pipes, pipe fittings, plumbing fittings, or fixtures, including backflow preventers, that are used exclusively for nonpotable services such as manufacturing, industrial processing, irrigation, outdoor watering, or any other uses where the water is not anticipated to be used for human consumption.4

This general language has caused concern, not to mention a host of hypothetical possibilities in which plumbing products could be installed, but repurposed in a different way than originally anticipated. In fact, except for adding an underline to the word “anticipated,” this article’s use of bold type matches the emphasis in the text of the law itself.

Other exemptions listed in the new law include:

- toilets;

- bidets;

- urinals;

- fill valves;

- flushometer valves;

- tub fillers;

- shower valves;

- service saddles; and

- water distribution main gate valves 50 mm (2 in.) or larger in diameter.

Additionally, the law does not require existing installations to be replaced. To its credit, it provides a single remedy to the patchwork of differing state laws that recently encumbered by the plumbing products industry. However, it does not address enforcement or compliance certification.

Instead, it says new prohibitions can be enforced by the states, and the existing framework under the older SDWA. The new law does not speak to requirements of third-party certification. However, depending on the location, third-party verification may be needed for products not in compliance with voluntary standards. Product marketing and packaging labels displaying compliance are also not required.

Additionally, in an August 2012 presentation, Jeffrey Kempic, an environmental engineer with the EPA Office of Ground Water and Drinking Water (OGWDW), said state and local governments, “may still prohibit the use of products that are not in compliance with voluntary standards. Independent third-party certification against those standards may be necessary depending upon the state/locality.” 5 While the federal law supersedes state law, states can include additional requirements including third-party certification.

Satisfying the new law

In order to comply with the law, but also to bring certainty to an uncertain market as a whole, manufacturers have had the opportunity to gain the trust of everyone associated with the specification and distribution of plumbing products by taking a holistic approach to the entire industry through education and discussions early in the design process.

It is a complex undertaking to smartly manage inventory and convert the manufacturing process. If a plumbing manufacturer is not in compliance soon, there could be serious problems. That being said, every specifier and architect should make certain they know where plumbing sources stand.

For example, manufacturing firms’ transition benchmarks (including educational efforts) can include:

- incorporating lead-free part numbers in order-processing to avoid mix-ups;

- initiating a leadership program for stocking distributors that provides a window of opportunity to purchase lead-free and exchange re-saleable standard products when they commit to the program;

- notifying engineers to update specifications because projects in the design phase this year could potentially be impacted; and

- encouraging engineers to inform clients about the new lead-free law and potential liability.

Similarly, this author’s company has worked with contractors, wholesalers, and distributors by providing tools to assist with their inventory conversion and to educate staff and customers.6

In addition to lead-free products, some manufacturers will continue making standard products for uses exempted from the new law. Therefore, it is incumbent on everyone to check with vendors to be certain they have measures in place to avoid cross-contamination of even minute levels of lead into the lead-free products.

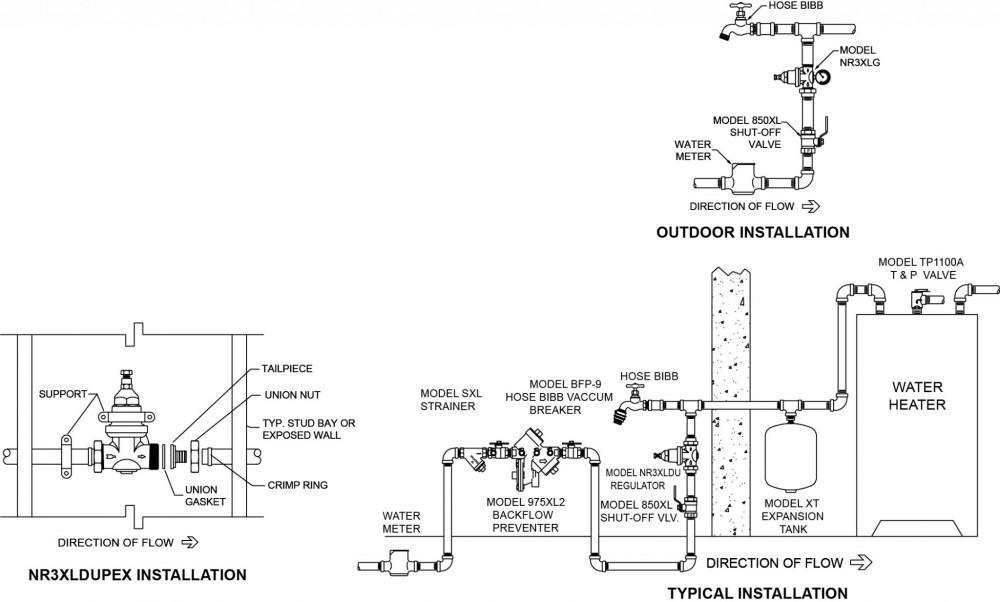

Contractors can prepare for the new law’s effective date by asking questions of their distributor and educating their own companies about how inventory will be impacted before and after the mandate takes effect. Additionally, contractors should familiarize themselves with lead-free product identification markings and installation techniques.

Specifiers and architects need to be certain they are working with people and companies committed to complying with the new law. This will ensure all parties understand and properly implement programs to ensure compliance once the federal law goes into effect. An area of concern is bidding. Those involved in the specification process must be certain job bids with standard products, or older, lead-containing products, before the deadline can be installed prior to January 4, 2014. If the standard products cannot be installed before that date, it will be illegal to install them after.

The plumbing industry uses the word ‘standard’ because the federal law can cause some confusion. For example, as previously mentioned, the current law defines ‘lead-free’ as eight percent. The new law defines lead-free as a weighted average of no more than 0.25 percent. Additionally, manufacturers will continue to make standard products for non-potable water uses.

Further, since lead-free products are often more expensive to manufacture, pricing expectations will need to be adjusted. If it is required to install lead-free products on a job after bidding less expensive leaded products, the project could cost more to complete than budgeted.

It cannot be stressed enough that specifiers, engineers, architects and those involved in plumbing decisions should make sure the design teams are in compliance with and understand the legal and business implications of the new law now, as well as after it takes effect.

The path to lead-free plumbing products began with a 1986 amendment to the SDWA establishing the maximum lead content in pipes and pipe fittings at eight percent and 0.2 percent for solder and flux (with the latter remaining in effect under the new law). In 1996, the federal government limited the lead content of end-point plumbing devices such as faucets and stops. In 2010, California and Vermont enacted limitations of the use of lead in plumbing fixtures that laid the groundwork for the federal mandate taking effect across the entire country this coming January.

California and Vermont

The experiences of plumbing-related companies in California and Vermont can serve as a lesson for the rest of the country. In these two states, a number of manufacturers, suppliers, and contractors tried to convert entire inventories of metal fittings, valves, solder, and pipe in too short a time—this led to big problems with inventory, material acquisition, and bidding.

The plumbing industry strongly agrees new lead-free products, with different chemical compositions, function and perform the same as standard products, requiring no design adjustments. They also meet all hydrostatic, tensile, and yield-strength standards. However, there was naturally a trial-and-error period before products were available for sale in California and Vermont.

One engineering manager in California—who lived through the state’s lead-free experience—says the learning curve was at least six months for foundries to determine the precise correct temperatures for pouring and to adjust the gating on the casting molds.7

As stated earlier, the conversion process has been complex. EPA itself has acknowledged the difficulty involved. During a public meeting at EPA headquarters in August 2012, with industry representatives in attendance, Pamela Barr, then-acting director of the EPA OGWDW, opened with these remarks:

When we first took a look at it, we really thought it was a pretty straightforward law. Take out eight percent, put in 0.25 percent; it is pretty easy. Even with our extensive processes, we should be able to do that easily. As we talked about it more amongst ourselves, and as we heard from some of you, we realized that it is not quite as easy as it looked at first blush. In fact, it is not really that easy at all.8

Also at this meeting, an EPA engineer outlined a number of unanswered questions in the new law regarding implementation. Questions posed included if and how a manufacturer should demonstrate its products are lead-free, and if there should be a third-party verification or self-certification with testing records made public.

Also, the issue of exempting products used exclusively for non-potable uses was addressed by Jeffrey Kempic who said:

To qualify for the exemption, must a product be physically incapable of use in a potable services application, or could it be physically capable of use but labeled as illegal for use in potable services? So the potential approach we have identified here is allowing the product line in potable or non-potable products that are interchangeable, if the non-potable version of the product is labeled as not for potable purposes. Or all the products that are interchangeable with a potable counterpart must meet the lead content requirement, because they are not used exclusively for non-potable purposes. So [in one scenario] there is potable and non-potable and [in the other scenario] there would be lead free, even if the use is a non-potable application as well.

He also discussed other unanswered questions, such as myriad possibilities for labeling the products and/or the packaging, and what to do when making repairs or replacements.

[The new federal mandate] prohibits the use of items that are not lead free in the installation or repair of a public water system or any plumbing in a residential or nonresidential facility that is providing water for human consumption. So the question for this one is, ‘Can the product in the system or facility be repaired using lead-free component parts and returned to service, even if the other component parts that are not repaired do not meet the definition of lead-free?’ We get a lot of calls on this one related to water meters. Does the entire meter have to be replaced or can a component part of the meter be replaced as part of the work?9

Code compliance

If EPA is asking such questions, inspectors may also be confused when reviewing plans to install a new plumbing system. It is this regulatory uncertainty that accounts for some manufacturer decisions to aggressively convert as many products as possible to lead-free.

There are three separate standards that apply to plumbing products:

NSF/ANSI 61

NSF/ANSI 61, Drinking Water System Components, includes a complex, robust performance approval process with a broad scope. NSF itself states the standard sets out minimum health effect requirements for materials, components, products, or systems contacting drinking water, drinking water treatment chemicals, or both. It covers everything from pipes and pipe fittings to sealants, adhesives, and liners. Its toxicology purview extends beyond just lead to include numerous other harmful metals and organic contaminants that may leach into drinking water from plumbing devices and fittings.

NSF 61, Annex G

This addition was developed to introduce an evaluation process for lead content when a product needs to meet a ?0.25% weighted average lead content requirement. This exists in California and Vermont.10

NSF/ANSI 372

NSF/ANSI 372, Drinking Water System Components–Lead Content, includes procedures needed to verify lead content in potable water products. Referenced in Annex G of NSF/ANSI 61, it includes the methodology to determine lead content compliance. Products certified to NSF/ANSI 372 are only compliant with lead content requirements. Meanwhile, NSF/ANSI 61, Annex G, certified products demonstrate compliance with both lead-content and lead-leaching requirements.11

Design engineer Reuben Westmoreland, says there would be more clarity for the industry if plumbing products were subject only to NSF/ANSI 372.

“When looking at the law by itself, NSF 372 is the appropriate way to demonstrate compliance that should be used by everyone for clarity and consistency,” he said. “The scope of NSF 61 is so broad compared to the requirements of the law, and that is why NSF 372 was created.”

The foreword to the NSF 372 standard states:

The NSF Joint Committee on Drinking Water Additives–System Components, determined that creation of a separate standard addressing lead content requirements would provide greater flexibility in the application of the lead content requirements to the marketplace and to organizations seeking to reference such requirements.

Conclusion

The uncertainty of where enforcement and certification is going should be ample motivation for specifiers, architects, and other industry members to over-communicate with plumbing product manufacturers and suppliers. It might take case law to settle the issues years from now, but in the meantime, the industry and customers will be asking, “Are we prepared?”

Notes

1 To view the full language of the law (42 USC 300G) prohibiting lead, including the Reduction of Lead in Drinking Water Act, visit www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/USCODE-2010-title42/html/USCODE-2010-title42-chap6A-subchapXII-partB-sec300g-6.htm. (back to top)

2 Visit www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/leadinwater/ and http://water.epa.gov/drink/info/lead/index.cfm. (back to top)

3 Visit www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/diseases/lead/en/. (back to top)

4 For more, see Reduction of Lead in Drinking Water Act, Federal bill S.3874 at www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-111s3874enr/pdf/BILLS-111s3874enr.pdf. (back to top)

5 See water.epa.gov/drink/info/lead/upload/leadfreedefined.pdf for more information. (back to top)

6 Visit www.zurn.com/Pages/LeadFree.aspx for more information. (back to top)

7 This information is from an interview with Chris Corral, engineering manager at Zurn Wilkins in April 2013. (back to top)

8 For more, see “Public Meeting Minutes, Reduction of Lead in Drinking Water Act Public Meeting,” at the U.S. EPA Headquarters in August 2012. (back to top)

9 See Note 7. (back to top)

10 The NSF-61 and Annex G descriptions are available at www.nsf.org/business/water_distribution/standard61_overview.asp. (back to top)

11 For more, visit www.nsf.org/business/newsroom/press_releases/press_release.asp?p_id=21830. (back to top)

Brad Noll has been director of engineering at Zurn Wilkins for 28 years. He holds a bachelor’s of science in industrial engineering and has been awarded numerous international and U.S. patents for water control products. Noll has played an instrumental role in converting to lead-free products at Zurn Industries LLC, and actively participates on numerous product standard committees related to the water control industry. He can be reached by e-mail at brad.noll@zurnwilkins.com.

To read the sidebar, click here.