by Karine Galla

Building material manufacturers that have historically incorporated various insulations into their assemblies are beginning to include mineral wool as an option to provide continuous, exterior thermal performance.

According to industry lore, mineral wool was spawned by an accident of nature first observed in Hawaii in the 19th century, when molten volcanic lava was stirred by the wind into fluffy fibers the natives then used as blanketing for their huts. A method of manufacturing this natural mineral fiber was first patented in the United States in 1870 by John Player, whose process involved blowing a stream of air across a falling flow of liquid iron slag. In 1897, American engineer Charles Corydon Hall developed a technology to transform molten limestone into fibers, thus launching the ‘rock wool’ industry in America.

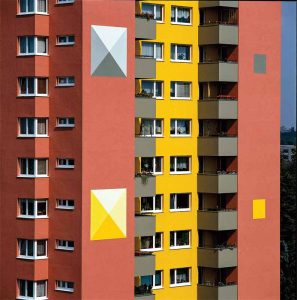

Photo courtesy Sto Corp.

Today’s mineral wool insulation is produced by cooking a molten mix of basalt or dolomite and slag derived from steel manufacturing in a furnace at a temperature of about 1426 C (2600 F). Through this mixture, a stream of air or steam is blown. More advanced production techniques involve whirling molten rock and a polymer binder using high-speed spinning heads (somewhat like the process used to produce cotton candy). The final product is a mass of fine, intertwined fibers with a diameter ranging from 2 to 6 µm (79 to 236 µin). It is composed of mostly inorganic material.

The individual fibers conduct heat very well, but when pressed into rolls and sheets, their ability to partition air makes them excellent insulators. The layered mat of fibers, which prevents the movement of air, provides a flexibility and versatility not found in most other insulations. Rock and slag wool can be produced in a wide variety of forms, shapes, and sizes, including board, batt, loose-fill, spray-applied, and pipe insulation for many common and specialized applications.

Mineral wool, for example, is widely used in industrial settings such as petroleum refineries and power plants to contain heat in pipes, tanks, and vessels. It is commonly employed for lofts, cavity walls, flat roofs, and heating systems. It also has been used as an insulation layer behind various claddings, especially curtain walls, spandrel panels, rainscreen façades, and now exterior insulation and finish systems (EIFS).