by Bert Slone

What constitutes a ‘mission critical’ building? How do the various parts of the building enclosure, particularly the roof, present challenges for insulating materials? What considerations should be taken into account when conducting cost/benefit analysis for mission critical buildings? Inspired by building science, insights from commercial construction in Europe, and feedback from architects, cellular glass is being re-introduced as an approach for insulating mission critical enclosures, specifically in commercial rooftop applications.

As every building has a mission or purpose to fulfill, a mission critical building for this article will be any facility with high-value processes, where a disruption in operations would impose significant human productivity or financial costs. Today’s mission critical buildings protect functions ranging from data processing and food manufacturing to national security. Research laboratories are carrying out scientific work where any interruption could discredit findings. Seamless communication transmission is vital for businesses involved in cyber security. Historic documents and ancient artifacts cannot be replaced should a leak occur in a roof. In mission critical buildings, a disruption in operations can threaten security, financial performance, productivity, and even human life. When viewed through this lens, it becomes evident many projects could be classified as mission critical.

The identification of mission critical building occupancies is addressed in Chapter 16 of the International Building Code (IBC). Table 1604.5 ‘Risk Category Designations’ identifies the risk category of buildings and classifies various code-defined occupancies housed in structures. For example, buildings housing critical communications, or functions essential to public welfare (e.g. water, electricity), or hospitals serving patients unable to egress a building on their own, all fall into the higher-value categories. These buildings are designed with additional factors of safety, or ‘redundancy’ to make them more ‘fail resistant,’ as well as to protect against weather and water.

Images courtesy Owens Corning

Redundancy supports reliability

Across all types of mission critical facilities reliability is a common denominator. Redundant systems that provide a back-up level of protection against failure are a key component of mission critical enclosures. In such buildings, the consequences of failure are costly, and thus, a high level of risk-benefit analysis is required. Architects must compare the economic cost of a building failure with the higher price of protective materials and systems.

The costs associated with a failure in the future should also be considered. The passage of time eventually stresses building materials, such as the roofing membrane protecting against moisture intrusion. Future remediation may be prohibitive in terms of logistics and economics. For example, in congested urban areas, the pathways and staging areas necessary to access and renovate or re-roof a building may be restricted, thereby, increasing the cost of the renovation. Hence, specifying a more expensive but durable building material at the outset of a project could be cost-effective in the long run.

Cellular glass

In all buildings, the roof is fundamental in protecting against water intrusion. In mission critical facilities, a leak in the roofing membrane can present very devastating consequences in terms of lost time and money. Therefore, a resilient, reliable, and redundant system is needed to protect in the inevitable event of a roofing membrane failure.

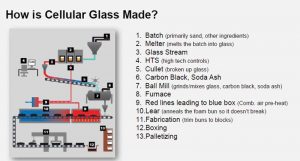

Long used in Europe’s commercial buildings, cellular glass is well-suited to deliver redundancy and back-up protection for commercial roofs. While architects with considerable tenure in the industry may recall working with cellular glass in the 1970s and ’80s, the introduction of foam plastics in the late 1980s shifted the nature of materials specified for commercial roofs. Foam plastics became the de facto standard for commercial roofs over the past three decades. Recent innovations in the cellular glass manufacturing process have resulted in an increased R-value from 3.66 to 4 per inch. The re-launch of cellular glass in the United States is reintroducing architects to a once-popular insulating material.

Although cellular glass is being relaunched in the United States, there are thousands of existing assemblies throughout the nation that include rigid cellular glass with a variety of membranes. Conversations with architects show that the U.S. market is embracing the concept, similar to European architects’ longstanding affinity for cellular glass and its performance properties.