by Michael McCoy

The recent prevalence of open offices, including address-free workstations and collaboration spaces, is a response to the need to accommodate an increasingly transient workforce. These wide-open spaces are typically designed to create more dynamic interactions among employees at all levels of an organization.

However, in recent years the elimination of walls and private offices combined with the continued use of hard surfaces such as concrete or wood floors, glass walls, and low-profile desks has led to the rise of new challenges related to confidentiality and acoustic comfort, resulting in an increase in the demand for acoustical solutions.

The American Society of Interior Designers (ASID) conducted a study in which 70 percent of workers reported they could be more productive in a less noisy environment (for more information, read “Productive Solutions: The Impact of Interior Design on the Bottom Line” by the American Society of Interior Designers [ASID]). Given that office workers spend approximately two-thirds of their time doing quiet work, addressing noise and reverberation issues is necessary to maximize employee productivity. The World Green Building Council (WGBC) estimates more than 90 percent of an organization’s operating costs are linked to employee efficiency. Research suggests when efficiency and productivity drop, operating costs are likely to increase.

Aside from productivity increase concerns, designing for the tech-savvy and highly engaged individuals constituting Generation Z can be a driving force for talent retention. As employers seek new ways to create more appealing and productive spaces that enable employee interaction, they also need to consider the privacy needs and acoustical comfort of the occupants.

Image courtesy Focal Point

Historically, designing for acoustic comfort meant installing acoustical ceiling tiles or wall panels, occasionally at the expense of aesthetics or other essential elements such as light levels. Today’s innovative materials are delivering flexible solutions addressing more than sound management and reducing echoes and reverberation issues, while enhancing other aspects of the interiors, such as lighting and aesthetics. To design acoustically optimized spaces and to select code-compliant materials, it is vital to understand the fundamental principles of sound control and to be aware of the organizations and the standards governing noise-mitigation strategies.

Basics of sound management

Three things can happen to sound as it moves through a space or medium: it can be reflected, transmitted, or absorbed. To design for acoustic comfort, it is essential to understand the ABCs of sound management where A stands for absorbing, B for blocking, and C is for covering up. Each of those strategies serves a different purpose, contributing to acoustical comfort.

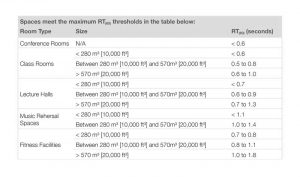

Materials serving as absorbers help reduce reflective sounds such as human voices, thereby decreasing reverberation time (RT) in a space. A material’s ability to absorb sound is measured by a noise reduction coefficient (NRC) or sound absorption average (SAA). In general, the higher the NRC or SAA, the better the sound absorption.

Noise barriers are used to block sound. In commercial offices, commonly used sound blockers are privacy dividers that help to reduce the impact of distraction from other people’s voices. Sound blockers can also be employed to reduce exterior noise (e.g. traffic or nature) or sounds originating from other floors, offices, or HVAC systems. Sound blocking is measured by sound transmission class (STC).

Sound masking helps maintain speech confidentiality and masks distracting noises, turning intelligible, distracting speech into unintelligible, non-distracting background noise. It is typically achieved with the use of ambient sound pumped through speakers.

Each principle has an intended purpose and should be used to optimize the acoustics of a space based on pre-determined parameters. This article focuses on sound absorption materials used to reduce RT.