A starting point for precast concrete finishes

by Sarah Said | September 7, 2018 9:08 am

by Tony Smith and John Carson

[1]

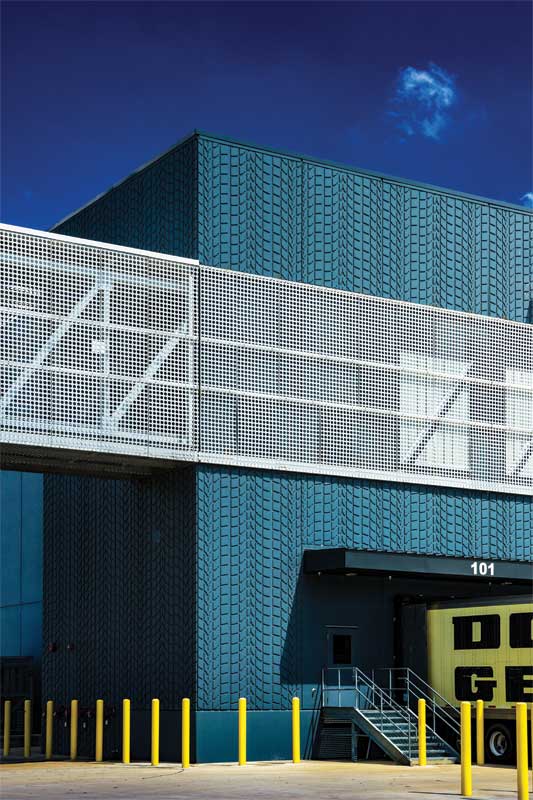

[1]The theme of transportation was dominant when architecture firm Leo A. Daly designed a five-building distribution center for Dollar General in Bessemer, Alabama. Rather than opting for a conventional finish on the warehouse’s precast exterior walls, the Omaha-based design firm sought a visual way to bring the theme to life.

Designers landed on a geometric pattern of an enlarged tire tread. They worked with a precast company headquartered in South Carolina to integrate the tread design into many of the wall panels comprising the façade. The distinctive and pleasing result differentiates the structure from other warehouses and speaks to the modern logistics operation inside the walls.

Applications such as Dollar General exemplify the aesthetic options possible with precast concrete; finishes complement the material’s low maintenance and durability properties.

Further, the controlled manufacturing environment enhances quality by giving manufacturing teams a predictable setting in which to integrate the finish into the exposed wall or enclosure surface. Forms are often used multiple times for consistency and cost efficiency.

Often associated with commercial, institutional, and industrial structures, precast concrete panels are also used in multifamily residential and student housing projects. The diversity of end-use applications demands flexibility in the finish options available to architects and designers.

However, selecting the ideal product requires a thorough understanding of finish characteristics and fabrication processes.

Understanding precast basics

The process of manufacturing precast wall panels influences the way in which finishes are imparted to the façade, so it is important to understand how they are fabricated.

Precast concrete walls are created in a “form,” or mold, typically in an offsite manufacturing facility protected from the elements. The form or casting bed is usually made of wood or steel. Reinforcements and prestressing strand is set in the form, and wet concrete is then poured, monitored, and cured. A layer of insulation is often integrated between separate concrete wythes, which are connected through the insulation by shear trusses if a sandwich wall is desired. The panel is removed from the mold, usually on the following day, and the mold is reused for other panels on the project. After reaching the specified strength, the complete panel can then be transported to the construction site, usually less than 805 km (500 mi) from where it is produced, and erected

into place either horizontally or vertically.

A primary advantage of precast concrete is the ability to express a variety of unique design aesthetics. Ironically, the durable nature of precast also presents a disadvantage—the finishes are “set in stone,” so it is essential to think long term. The types of precast finishes can be grouped based on the concrete’s component elements, treatments, casting process (i.e. special forms), embedments, or graphic images. Each of these finishes is described below.

Component elements

The primary components of concrete—cement, aggregate, and water—have a major impact on the finish. Any aesthetic finish starts with the concrete’s mix design.

The aggregate and cement color can be selected to achieve both functional and aesthetic results. Conventional gray cement is the choice for many industrial buildings, while white cement can provide a modern, clean look. Pigmentation refers to additives to the mix design that incorporate color at an integral level. Essentially, cement color is the “default” color for the panel; it is the visible element when not displaced by aggregates or covered by embedded materials like thin brick or tile.

[2]

[2]The precaster used a custom formliner to replicate an enlarged tire tread pattern on a Dollar General distribution center in Bessemer, Alabama.

Photo courtesy Metromont

Aggregates further impact the look of the final product. Coarse aggregate yields a rough, bulkier texture and more sedimentary appearance, while finer aggregate yields a smoother look and feel. Aggregate color, composition, and texture can vary widely based on geographic availability. It is wise to consult with precasters in the region before specifying a finish depending on a specific aggregate as it may not be readily available.

Color generally refers to a surface-level addition, such as paint or stain, applied to the precast surface in the factory or field. A number of commercial options are available. It is critical to specify a paint or stain formulated especially for concrete. Surface preparation is often a requirement.

The Heights at Montclair State University, New Jersey, serves as an example of how these finishes can be combined to meet aesthetic goals and achieve sustainability objectives (see page 46). The school’s original 1908 buildings had a Spanish Mission style officials hoped to see reflected in the new building. For the two-tower, 1600-student project, PS&S Architecture out of Warren, New Jersey, designed exteriors reminiscent of the original stucco, but with the ability to achieve modern aims including durability and a minimized carbon footprint.

The precast concrete was manufactured within 805 km (500 mi) of the project, using at least 90 percent materials from within the same radius. This helped with the carbon footprint, as did using fly ash in place of some of the Portland cement. The fly ash did not impact the finish. Buff and white colors connected the building with its stucco forebears.

[3]

[3]Photo © Josh Partee

Treatments

A number of techniques applied post-fabrication can modify the precast finish and provide various expressions of the mix design. Sandblasting yields a softer concrete surface with coarser aesthetics when properly prepared. Finishes of exposed aggregate give a distinctly rough, pebble-like look to the surface and are achieved by the application of a chemical retarder. The retarder slows the hardening of the panel’s surface, allowing the unhardened matrix to be pressure-washed away to expose the aggregate.

Polishing, as the name suggests, leads to a smooth, shining, reflective surface similar to granite. Acid wash involves using acid and high pressure water to blast and etch the surface, leading to a sugar cube-like look—a smooth, sand-textured surface resembling limestone or sandstone. A fossil finish uses a chemical reaction to produce a pattern suggesting fossils;

it can yield a beautiful finish when paired with a carefully selected pigmentation. Of course, multiple finish techniques can be incorporated into the project for creative results.

Casting process

Another group of finishes originates during the casting process; namely, forms and formliners. A formliner, as the name suggests, lines the precast form. Wet concrete will be displaced by any form that is in the mold. Formliners are fabricated from polymers using computerized machining. Formliners can impart enhanced texture, such as a repeating pattern or single design element, and add depth to the panel face. The use of formliners opens up several options. However, it requires close coordination between the architect and a precaster to ensure the desired form is practical given the concrete mix design, configuration of panels and their joints, and repeatability of image.

Sandy High School in Oregon has a predominantly precast façade reflecting regional culture and natural formations (see page 48). A custom stone formliner for the base of the school and a shiplap liner for the upper portion were developed as a cost-effective and efficient alternative to solid stone. It expressed the aesthetic the architect wanted as well as elements of the Pacific Northwest region in which the building stands without the expense and labor associated with stone.

A variety of more conventional architectural forms enable architects to impart accents and relief into the precast or deliver a repeated pattern across the façade. The forms can be quite simple, such as reveals—a notch of a specific width and depth helping break up a broad expanse of wall or mimic the aesthetic of large stone. Reveals often complement the joints between the precast panels to help turn the joints themselves into aesthetic rather than merely functional elements.

[4]

[4]Photo courtesy Metromont

Multiple reveals in the buff-colored face give the impression of cut stone to complement the geometry of the brick façade at Willow Creek Elementary School in Fleetwood, Pennsylvania.

Cornices are horizontal decorative features “crowning” the building, expressing a certain design aesthetic. Bullnoses are smooth, rounded edges that may be a simple rounded corner or a significant protrusion adding interest with light and shadow. Projections such as these are integrated into the mold and frequently repeated from panel to panel.

For the Heights towers, the cornices express the original low, wide Spanish Mission-style roof. In addition to respecting past architectural styles, the project also sought to entice commuter students to live on campus by offering attractive buildings in addition to the views of Manhattan. The panels include bay window projections, reveals, and bullnoses for added visual intrigue and design expression. Without them, the buff finish would have looked flat and sterile.

Embedments

A fourth group of precast finishes are embedded materials or veneers. These include thin brick, stone, and tile cast into the panels during fabrication. By incorporating these finishes into the panel during the cast, architects can avoid the use of pins or connectors used to secure the stone to the substructure. Precast offers a faster, more durable, and sustainable method to incorporate these finishes. They usually require a formliner with inset areas to locate the brick, stone, or tile. They also have keyed backs to ensure proper placement and spacing. Any space between the embedded materials shows the concrete mix, which resembles mortar.

Piedmont Central Student Housing and Dining Hall at Georgia State University (GSU) features extensive use of thin brick in combination with other finishes (see photo at left). Approximately 2415 m2 (26,000 sf) of cast-in red thin brick complemented nearly 11,148 m2 (120,000 sf) of medium sandblast finish with a limestone color. Selected vertical runs of precast panels were painted blue to reflect GSU’s colors.

The Bloch School of Business in the University of Missouri-Kansas City, Kansas City, Missouri, with 1784 m2 (19,200 sf) of 3.6-m (12-ft) wide, fully insulated composite panels was the first building of such scale to use embedded terra cotta (see page 44). With a five-color random blend, these precast walls were lauded for their effectiveness as rain barriers compared with conventional rainscreen configurations. The precaster used color-coded instructions in the production facility to carefully place each individual piece of tile into the form as directed. Meticulous use of sealants kept the grey precast out of view, leaving the joint as a shadow. This special project required extensive cooperation between the architect, client, and precaster.

[5]

[5]Photo courtesy Graphic Concrete

Graphic image

A relatively new option for precast in North America is graphically imaged concrete. The graphic finish can range from a photograph to any type of pattern or design to render a stunning, iconic look. The graphic finish can be repeating

or non-repeating.

A surface retarder on a printed membrane is placed at the bottom of the form. Concrete is cast atop the membrane containing the reversed image. After the concrete is cured and extracted from the form, the retarder is rapidly washed away with a high-pressure washer, revealing an image resulting from the contrast between the fair faced (smooth) and the exposed aggregate surface. The amount of definition in the design can be controlled by the strength of the retarder and the color variation between the cement and aggregate. Though it cannot be reused, the membrane itself is recyclable. This finish is just as low maintenance—and permanent—as any of the other precast concrete finishes.

A standout example of the possibilities can be found in Denmark. RUM Arkitektur originally won a contract to design a new copper-clad Rødkilde Gymnasium (see page 50). The nearby courtyard would be a social gathering place and learning hub. Copper cladding proved too expensive, so the firm looked to graphic finishes on exposed concrete, aiming to tie in with the school’s older concrete buildings. For a distinctive element and to bring in the “new,” the students and staff were encouraged to write words, statements, and formulas. These were then incorporated into the graphic finish, making the building truly the school’s own.

For this type of finish, it is advisable to discuss the project with a precaster to ensure the specification meets the aesthetic expectations of the architect. Small adjustments to the aggregate or retarder strength can result in superior imaging. Test panels are commonly produced to ensure the mix design and graphically imaged membrane work together to produce the desired aesthetic.

Evaluate, consult, specify

While precast concrete can carry the misperception of being hulking or bland, the availability of a variety of finishes belies this bias. From variations in the mix design and treatments to embedded elements and graphically imaged concrete, precast may be one of the most versatile palettes for architectural expression.

Specifications often include class certification from organizations like Precast Concrete Institute (PCI) and Canadian Prestressed Concrete Institute (CPCI) to ensure adherence to best practices and modern manufacturing processes for architectural precast. Specifying travel distance between the precast facility and jobsite (usually less than 805 km [500 mi]) is also typical, especially if adhering to green building practices. Specific aesthetic treatments should be reviewed with one or more precasters to make sure there is enough detail to allow the contractors to estimate costs and production timetables accurately.

Overall, precast concrete can deliver a multitude of unique finishes complemented by all of precast concrete’s advantages of low maintenance, production efficiency, and resilience. Specifying the proper finish requires an understanding of the architect’s vision and coordination with certified regional precasters to ensure the outcome.

Tony Smith is vice-president of preconstruction and marketing for Metromont Corporation, a precast/prestress concrete manufacturer. He has been with Metromont for more than 27 years with experience in drafting, estimating, sales, business development, and marketing. Smith can be reached via e-mail at tsmith@metromont.com[6].

John Carson is executive director of AltusGroup, a partnership of 19 North American precast companies dedicated to precast innovation powered by collaboration. A graduate of North Carolina State University, he has more than 35 years of technical business development and strategic marketing experience. Carson can be reached at executivedirector@altusprecast.com[7].

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/MontclairState1.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/DollarGeneral4.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/SandyHS-JoshPartee-4316-NE-precast-dtl.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/GSU-Piedmont2.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Roedkilde_Gymnasium_GCProÖ_DK_300dpi_004.jpg

- tsmith@metromont.com: mailto:tsmith@metromont.com

- executivedirector@altusprecast.com: mailto:executivedirector@altusprecast.com

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/a-starting-point-for-precast-concrete-finishes/