by David Ingersoll

Whether they are selecting options for drywall, ceiling panels, or lighting fixtures, project teams are expected to be experts, know the ideal solution for every scenario, and to deliver it on time and on budget. Beyond this baseline is the need to create an environment that performs behind the scenes, keeping intrusive noises at bay and allowing the space to function as intended.

In a world with limitless options for even the most rudimentary of projects, this can be a daunting challenge. It especially rings true in cases that go beyond aesthetics where clients enlist contracting teams to find solutions that meet specific functional requirements, including acoustical performance. Proper acoustics are required for almost every type of facility where noise collects. It can have a significant impact on the building owner’s long-term satisfaction with the space and the work performed by the contractor. Proper acoustical planning can improve speech intelligibility, minimize disruptive reverb/echo, improve individual comfort levels, and increase worker productivity.

Before developing a solution for new construction projects and building renovations, it is important to understand fundamental acoustical terminology and principles. The ABCs of acoustical performance begin with sound measurement and how sound absorbers, barriers, and composites can reduce overall noise.

In general, we consider sound to be anything heard by the human ear. Two ways in which sound is measured is by its intensity and tone. Sound intensity is measured in decibels (dB), and the goal of proper acoustical treatments is to provide a specific decibel reduction depending on the space’s intended use.

The second critical measurement for sound is tone, which can be described by the frequency of sound waves measured in hertz (Hz). For example, the average frequency of most common noises is around 500 Hz. This is why so many acoustical calculations are made at this frequency.

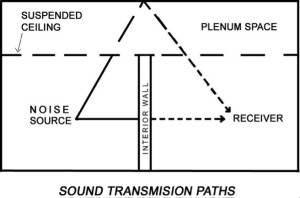

Another factor to consider with acoustical treatments is omni-directional sound—sound that travels in every direction at the same velocity. The image below shows the paths in which sound can travel from one room to another. This speed can cause sound to easily travel upstream in any air duct or ceiling without acoustical treatment.

The three basic categories of treatments—sound absorbers, acoustical barriers, and composite materials—must be understood to help identify which acoustical products will work best for a project. These materials should be installed during construction to be most cost-effective and to save correcting problems later. When construction teams work in tandem with acoustical engineers, headaches can be avoided in subsequent phases of the project. Additionally, labor rates will generally be lower if acoustical treatments are specified early. This means the general contractor can layer acoustic pieces during construction, rather than hiring costly specialty contractors to install solutions after the fact.

Absorbers

An absorber is defined by its ability to change sound-energy into heat-energy on contact. It is used to help improve sound within a space or to increase speech intelligibility. When a sound wave strikes an absorber surface, it is soaked up like a sponge; it isolates the noise, rather than reflects it back into the room.

Materials that ‘absorb’ do so by reducing reflective sound. They are typically fibrous or open-celled materials, such as foam or medium-density fiberglass (MDF) board. Absorber materials change acoustic energy into heat using friction.

Each material’s ability to absorb sound is measured with noise reduction coefficient (NRC) ratings. By giving early consideration to the room’s finishes and surfaces, the acoustical engineers can ‘tune’ the room for optimal performance based on the end user’s needs. Absorptive materials improve the acoustics within a room, but they do not affect room-to-room sound transmission. To decrease sound transmission (i.e. the noise you hear coming from an adjacent room), acoustical barriers are used.

Barriers

Noise barriers help block or isolate sound from passing from one space to another. Sound turns a wall into a speaker diaphragm that transmits the waves to the adjacent space. Therefore, the more mass a material has, the better its ability to block sound.

Measuring the effectiveness of a barrier or the loss of sound transmission is said to be a material’s sound transmission class (STC) rating. A project team may choose materials that block outside or adjacent noise where it is essential to control noise from one room to another, such as in apartments or office settings.

A noise barrier requires mass, making it more impervious to sound waves. Thus, products that are heavy and denser than absorbers are used to block sound from passing from one space to another. Barrier materials include vinyl, rubber, and concrete with typical building materials like gypsum board being the most commonly used materials in building construction. New materials such as mass-loaded vinyl are used to add weight to a wall ceiling or floor in a thin layer.

In music halls and other buildings like so, its quite interesting if you take a look around. One of the things that you will notice is how the walls and the ceiling of the room take shape. They are formatted in a certain way so that the sound waves will travel well and not be muffled out. I do like the picture you used to show how sound waves will move from one room to another.