by Matthew Blakeley

Lighting in commercial buildings has long been governed by functional and economical standards and architectural considerations. The questions of how much light is required to make the space safe and functional, and how illumination can be delivered economically, constitute the basis for light source selection. This is also driven by stringent efficacy (i.e. energy savings) standards supporting sustainable architecture and design. For high-end spaces, a design concern may guide the choice of statement luminaires, or specialty light sources whose function is to highlight architectural elements.

A new paradigm, referred to as human-centric lighting, or lighting for human preference, where light is seen from the perspective of the users of a space is starting to emerge. The results of recent independent studies provide a foundation for designers to specify a spectrum humans prefer. This type of spectrum can help achieve more natural skin colors and warmer wood tones, increased vibrancy of objects, and a pleasant environment for building occupants.

New certifications such as the WELL Building Standard and recent test methods provide arguments for the use of higher quality light sources for the well-being of occupants, as well as the means to define the parameters of luminaires.

Greater efficiencies have continuously been achieved over the last 50 years. With the progression from incandescent light bulbs and fluorescent lamps to light-emitting diodes (LEDs) as primary illuminants employed in commercial spaces, it is time to shine the light on the humans who spend a large portion of their time in commercial buildings, and to select fixtures with the ability to contribute to their wellness.

Evolution of light sources

Photos courtesy Focal Point

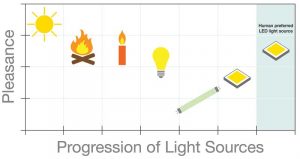

The sun was the first light source known to humans, followed by the discovery and control of fire, several hundreds of thousands of years ago. Candles and other similar sources of light were used until the invention of the Edison incandescent light bulb in 1879, less than a century-and-a-half ago.

Thomas Edison was not wrong when he said, “We will make electricity so cheap that only the rich will burn candles.”

Candles are not only impractical, but electrical light sources have also evolved way beyond the incandescent light bulb to provide increasingly powerful, reliable, economical, and efficient lighting over time.

However, the warmth and comfort associated with the sun, fire, and incandescent bulb is not found in light sources that have followed. Since the 1950s, luminaires have achieved better efficacy, but this gain corresponds to a drop in the perceived warmth and comfort of each type of fixture. During the 1970s, one got used to brightly lit spaces with a green glow typical of fluorescent lamps. This continued with the first LEDs that gained mass appeal in the early 2000s. It had been necessary, at that time, to tweak the spectrum by increasing the green content and reducing the red, so the LEDs would produce the maximum amount of light possible and make this new technology a viable replacement for fluorescent lamps.

This tradeoff is no longer necessary. Therefore, the discourse can shift from quantity to quality, and the resulting benefits of light sources matching human preference.

Measuring quality of light

Released in the 1960s, the color rendering index (CRI) is the most common measure for light color quality. It is only a measurement of fidelity, as it describes the accuracy of a light source to a reference illuminant (i.e. a blackbody radiator) on a scale up to 100. A score of 80 CRI is considered acceptable and has become a baseline for most light sources specified in commercial environments. Having said that, 90 CRI is the common specification point used today for high quality as it is more similar to the reference illuminant.

As explained, CRI is a single number, an easy-to-understand rule of thumb describing how a light source differs from a reference illuminant without describing the direction of change in either chroma or hue. In simple terms, chroma refers to the intensity or saturation of colors, while hue is the coloration. For example, not all reds are the same because some contain more blue tones while others have more red or yellow. Using CRI as a means to measure color quality may result in over- or under-saturated illuminants, possibly in different hues and resulting in distinct light qualities even though they have the same CRI.

In 2015, the Illuminating Engineering Society (IES) launched TM-30, IES Method for Evaluating Light Source Color Rendition, to provide an accurate description of LED light sources. An updated version (TM-30-18) was recently released.