Affordable solutions available for better school acoustics

by Katie Daniel | June 2, 2016 10:55 am

by Stephen Lind

Experts believe as many as one-third of all school students miss up to 33 percent [1]of the oral communication that occurs in the classroom. Acoustics play an important role in creating a productive indoor environment and are especially critical in schools. Since much of K−12 learning hinges on hearing the teacher, sound control is a critical component of a high-performing school.

Research shows excessive background noise or reverberation in classrooms interferes with communication and listening and thus impedes learning. Additionally, poor school acoustics create extra challenges for students coping with learning disabilities, hindered by impaired hearing, or struggling to learn in a non-native language. (For more, see P. Nelson and S. Soli’s article, “Acoustical Barriers to Learning: Children at Risk in Every Classroom,” which was part of the October 2000 [vol. 31] edition of Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools). Numerous articles in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America (JASA) have highlighted studies showing students learn faster and comprehend and retain more knowledge in environments with the proper acoustics.(Examples from the periodical include “How Room Acoustics Impact Speech Comprehension by Listeners with Varying English Proficiency Levels” by Zhao Peng et al [vol. 134, 2013], and “Effects of Room Acoustics on Subjective Workload Assessment While Performing Dual Tasks” by Brenna N. Boyd, Zhao Peng, and Lily Wang [vol. 136, 2014]).

Due to these factors, design requirements for school acoustics differ from other commercial building spaces. The Acoustical Society of America (ASA) has created an American National Standards Institute (ANSI) classroom acoustical standard—discussed later in this article—to help ensure schools are designed correctly to create conditions conducive to learning.

HVAC equipment can play a key role in helping schools create quiet, comfortable classrooms for students and teachers. There are some considerations to keep in mind, but it is possible to meet classroom acoustic requirements with standard mechanical equipment and off-the-shelf components without adding significant costs in typical installations.

The importance of acoustics

Children can be ineffective listeners as they are still developing their speech perception abilities. This makes it difficult for them to separate speech from background noise or to correctly distinguish what is being said. Children need good acoustics to understand even familiar words and to learn new information. (P. Nelson’s article,“Sound in the Classroom: Why Children Need Quiet,” was in the February 2003 edition of ASHRAE Journal [vol. 45, no. 2]). These issues can be especially critical for students with learning disabilities or hearing impairments, as well as those dealing with common ear infections that can cause temporary hearing loss.

As children have different acoustical needs, neither engineers nor architects can rely on practices considered acoustically acceptable for adults when designing school spaces for teaching kids. There are both internal and external sound sources that impact noise levels in a school that need to be considered. External environmental factors can include nearby highways, airports, or rail lines.

Building mechanical systems, as well as school HVAC equipment with moving parts, can also contribute significantly to noise in a classroom. Fans, compressors, motors, and high-velocity fluid are the most common sources of distracting sound. Steady-state operation has been the focus of most standards and guidelines, but transient sounds due to starting and stopping can also result in disturbing or excessive noise. If acoustics are not considered when the building is designed, it is easy for mechanical equipment noise to become excessive in the classroom.

Standards for schools

The acoustical design standards for classrooms developed by ANSI through ASA differ from those for other commercial and institutional buildings. ANSI/ASA S12.60, Acoustical Performance Criteria, Design Requirements and Guidelines for Schools, states the minimum set of requirements to help school planners and designers provide good acoustical characteristics for classrooms and other learning spaces. (The standards are available for free download at www.acousticalsociety.org[2]). These requirements for permanent classrooms are based on room size and include maximum background levels for A- and C-weighted sound pressure levels (dBA and dBC) and reverberation time.

A growing number of states are adopting the ANSI/ASA standards, signifying the increasingly important role of acoustics in school design and planning. The U.S. Access Board, a federal agency that promotes equality for people with disabilities, is also working to get the standards adopted into building codes across the country. The Access Board recently collaborated with the International Code Council (ICC) to put the criteria determined by ANSI/ASA into the building codes dealing with accessibility. ICC is working on putting these requirements into the International Building Code (IBC) currently being written and to be published in 2018. (Currently, the accessibility references can be found in 1207.1 and 1207.3.) Additionally, there are standards from the Air-conditioning, Heating & Refrigeration Institute (AHRI) dealing with the recommended sound ratings of HVAC equipment used in schools.

Testing done by this author’s company in a simulated classroom environment showed the recommendations of the standard can be easily met using commercially available, off-the-shelf HVAC products and industry-accepted design and installation techniques. Acoustics are a design parameter and must be dealt with during the design of the project.

The systems tested included a packaged rooftop unit, a blower coil air-handler, and a high-efficiency water source heat pump. Testing proved the standards could be met at a less than one percent additional cost for typical installations, demonstrating the importance of considering good classroom acoustics at the start of a project.

Technology for quieter classrooms

Being aware of the specific acoustic requirements for schools—and understanding how they are different than those used for other buildings—is the first key step in planning for and addressing classroom noise levels during the design phase. One challenge faced by many schools is the need to put equipment in the classroom while still having it be quiet enough to meet acoustic standards. In these cases, placing the equipment in a small closet, an enclosed mechanical room, or above a nearby corridor can help decrease the noise level for the teacher and students.

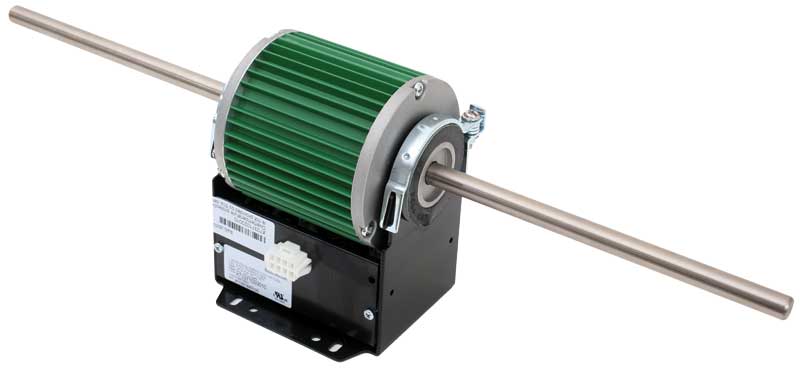

When those options are unfeasible, it becomes a matter of selecting quieter mechanical products.7 (Price points can vary from no change over traditional equipment to increasing that initial price tag. It is important to do a lifecycle cost analysis for each project. For example, electronically commutated motor [ECM] technology has a larger up-front expense, but offers better lifecycle costs because of how efficient they are). It is important to look for equipment that is AHRI-rated and labeled to ensure it meets specific acoustic specifications. It is also critical to ensure the acoustic rating is for the whole unit, rather than for just one component, such as a fan or compressor. Manufacturer testing of the entire assembled air-handling unit (AHU) is a recommended practice to provide the most accurate and reliable acoustic data.

Another option for decreasing the noise level of HVAC and mechanical equipment is to implement various acoustic treatment options. These solutions include using duct lining materials and silencers to help achieve lower sound levels. Additionally, significant progress has been made by the industry in developing ultra-quiet technologies, such as a recently introduced air-cooled chiller that is 8 dBA lower than others on the market.

Electronically commutated motors (ECM) technology can also help ensure quieter equipment performance by allowing the unit to be programmed to vary the motor speed and power. This enables the equipment to run at a lower, and typically quieter, speed when necessary—this reduces sound levels in classrooms while they are occupied.

Larger schools can consider the option of installing a centralized chiller plant, which can be placed at a location farther away from classrooms, in order to help minimize the acoustical impact on critical learning environments.

Investing in quieter HVAC and mechanical equipment can provide benefits in other ways as well. For example, selecting quieter equipment may reduce construction requirements and necessary investment in thicker windows or ceiling acoustic treatments.

A practical example

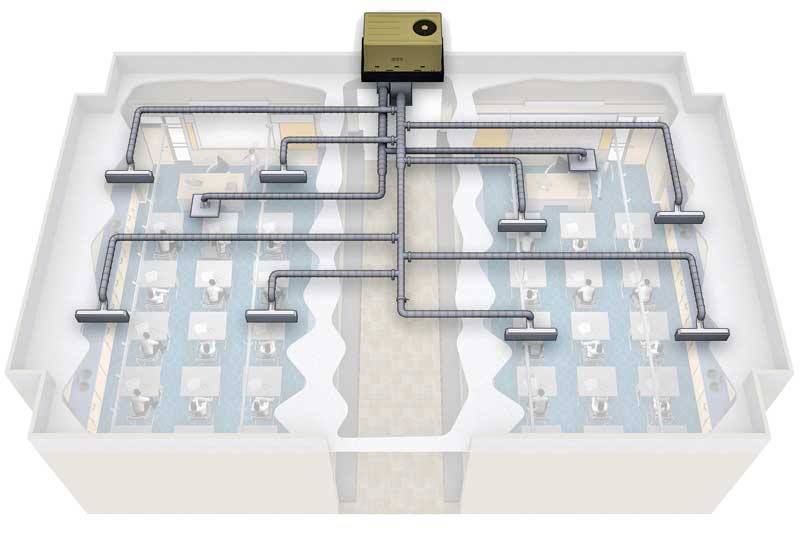

Figure 1 shows a hypothetical installation of a pair of classrooms using numerous good practices for meeting ANSI S12.60. The unit is over a corridor, which reduces breakout sound directly into the room and allows attenuation before entering the room. Both the supply and return are ducted, allowing a chance for attenuation. Linear slot diffusers are used, and they are often quieter or can be installed with a desirable length of straight duct before the diffuser.

Placing the diffuser as the noise-generating device closest to the room is critical in meeting the standard. If there are turns or elbows close to the diffuser, it can easily increase the generated sound beyond the rated sound from the device. Further, the use of sound ducts would need to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, because they can reduce the breakout noise but may also reduce attenuation of sound traveling within the duct. Finally, there are acoustic plenums below the unit, which allow for a significant sound reduction between the unit and the ductwork.

Helpful resources available

There are numerous resources that can be of help when considering HVAC equipment. These resources include acoustical analysis software that may accurately predict and compare sound levels of various HVAC systems and construction plans. The software takes into account different sound sources and accurately predicts a classroom’s sound level, which helps in selecting the right solution during planning and design. Inputs include specific building requirements along with the type and placement of HVAC equipment, duct configuration, and wall and ceiling type. Equipment manufacturers offer this type of acoustical analysis and software. The American Society of Heating, Refrigeration, and Air-conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) also has an HVAC Applications Handbook that provides guidance on conducting an acoustical analysis.

Bringing in an acoustical consultant familiar with the requirements early in the process can also help prevent issues and save money down the road. The National Council of Acoustical Consultants (NCAC) is an organization that can provide guidance and help in selecting a consultant for a specific project.

Sound levels that promote learning

HVAC noise can be a common culprit in noisy classrooms. Excessive noise and reverberation interfere with speech intelligibility, resulting in reduced understanding and learning. Engineers and architects need to consider all the sound sources impacting a classroom space.

School acoustic standards provide guidance on maximum background noise levels and reverberation times for optimal learning. It is important to be aware of these standards—and know there are feasible and affordable options available to help meet them. When the system is properly designed, excessive mechanical noise can be substantially reduced at little or no extra cost.

In the end, a good listening and learning environment is achievable when classroom acoustics are considered at the outset of the design process, and with early collaboration among school planners, architects, contractors, and suppliers.

Stephen Lind is an acoustics engineer in sound and vibration testing at Trane, a supplier of indoor comfort systems and solutions, and a brand of Ingersoll Rand. His work focuses primarily on measuring sound for air-conditioning systems—he is active in the Air-conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Institute’s (AHRI’s) Technical Committee on Sound and on the Acoustical Society of America (ASA) Standards Committees S1 and S12. Lind received a degree in physics from the University of Northern Iowa and a master’s in engineering (acoustics) at the University of Texas at Austin. He can be reached via e-mail at slind@trane.com[3].

- 33 percent : http://www.schoolconstructionnews.com/articles/2005/12/9/acoustical-standards-begin-reverberate

- www.acousticalsociety.org: http://www.acousticalsociety.org

- slind@trane.com: mailto:slind@trane.com

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/affordable-solutions-available-for-better-school-acoustics/