However, the energy used by a building after it is constructed also contributes to carbon emissions. This is called operational carbon. Taking into account embodied carbon, the material’s contribution to reducing operational carbon, and the end-of-life stage is the most accurate way to get a full picture of a building product’s complete carbon footprint.

EPDs: An incomplete picture

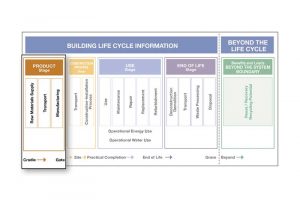

To manage carbon, most building and construction experts make decisions based on disclosures made through lifecycle assessments (LCAs) and related International Organization for Standardization (ISO) Type III ecolabels such as Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs). These documents use international standards (e.g. ISO 14040 and ISO 14044) developed by ISO Technical Committee 207 on environmental management. LCAs collect environmental information throughout a product’s lifecycle—from raw material extraction to its final use and ultimately to its disposal. Since these documents are often lengthy, they usually include a summary page of the results. EPDs are one such standardized summary of an LCA.

An EPD for a given material is created within boundaries described in a product category rule (PCR), as defined by ASTM. The PCR for single-ply roofing membranes, such as PVC, permits the use of information from either extraction, transport to factory, and manufacture, called a declared unit (“cradle-to-gate”) or all of that plus service life and recyclability, called a functional unit (“cradle-to-grave”).

Since there is no requirement in the PCR to include the functional unit in their EPDs, many manufacturers elect to use the declared unit, the cradle-to-gate method, to derive content for their EPDs. When there are tools in the marketplace pulling portions of the cradle-to-gate modules, it is important for users to understand the limitations on comparability when important product attributes, such as durability and recyclability, are not being considered. The absence of these factors may result in fewer sustainable product selections. Purchasers should consider this when making purchasing decisions.

Most, if not all, PCRs for construction materials draw from ISO 21930: 2017. For example, the PCR for single ply roofing membranes notes in section 5.5, comparability of EPDs for construction products:

-

These calculators have been limited to what are referred to as the A1-A3 impacts (i.e. cradle-to-gate) for a single purchase of a product. A more accu-rate way to measure embodied carbon is through cradle-to-grave calculations, which take into account the entire product lifecycle. Photo ©2020 The Institute of Structural Engineers (IStructE) “…It shall be stated in EPDs created using this PCR that only EPDs prepared from cradle-to-grave life-cycle results…can be used to assist purchasers and users in making informed comparisons between products.”

- “EPDs based on ‘cradle-to-gate’ and ‘cradle-to-gate with options’ information modules shall not be used for comparisons. EPDs based on a declared unit shall not be used for comparisons.”

While cradle-to-gate values are accurate to a point, they can also be misleading and not paint the full picture. Design professionals must exercise due diligence by selecting materials suited for the specific requirements of individual buildings and applications.