Are all zinc coatings created equal?

by Katie Daniel | March 7, 2016 4:54 pm

by Melissa Lindsley

Zinc is naturally found in elements such as air, water, and soil as well as in plants, animals, and humans. It is the 27th most abundant element in the Earth’s crust and is infinitely recyclable without the loss of its properties, making it a true renewable resource.

Zinc’s ability to protect iron and steel products from corrosion has been known for centuries as the material has been used in construction since the second century. More than 13 million tons of zinc is produced annually worldwide—70 percent of which is from mined ores and the remaining is from recycled sources. More than half of this annual production is used in zinc coatings to protect steel from corrosion.

Today, there are many types of zinc coatings, often referred to generically as ‘galvanizing.’ The most common used in construction applications are:

- batch hot-dip galvanizing;

- continuous sheet galvanizing;

- zinc-rich painting;

- zinc spray metallizing;

- mechanical plating;

- electrogalvanizing; and

- zinc plating.

All these coatings have unique characteristics, corrosion resistance, and performance—in other words, not all zinc coatings are created equal. This article will help architects, engineers, and other specifiers understand the differences between the zinc coatings, and therefore select the most suitable one for their project.

How zinc protects steel from corrosion

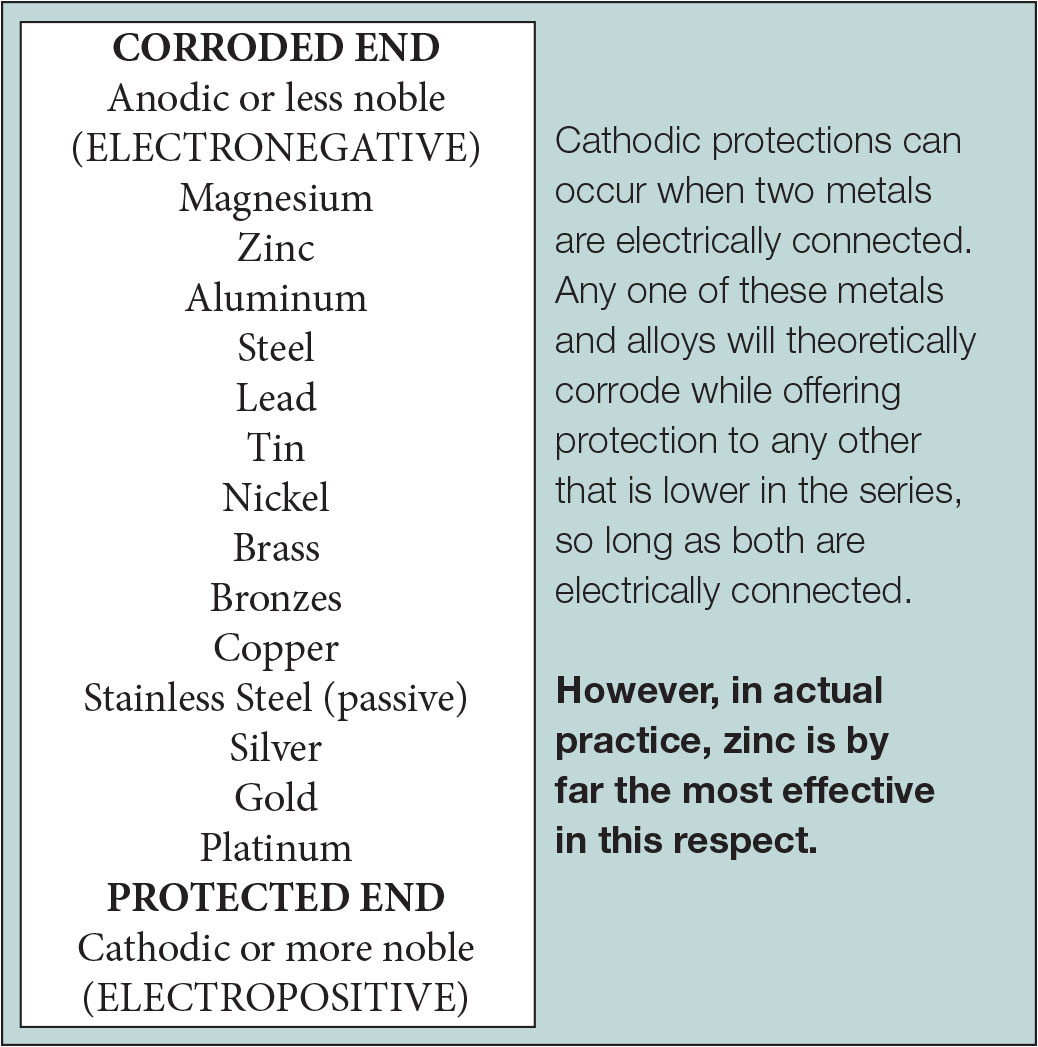

All zinc coatings provide basic barrier protection by isolating the steel from exposure to the environment. However, there are two additional protective benefits when using zinc to protect steel from corrosion: cathodic (sacrificial) protection and the zinc patina. Whenever two dissimilar metals are in contact, one metal (anode) will preferentially corrode while the other (cathode) is protected. Zinc coatings exploit this phenomenon by using zinc to protect steel.

The “Galvanic Series of Metals,” which lists metals in order of their electrochemical potential in the presence of salt water, defines which will be anodic when two metals are connected. Metals higher on the list will become anodic to those lower in the series. Zinc is higher than steel on the scale, and therefore, zinc will sacrificially corrode to protect the underlying steel.

In addition to the natural barrier and cathodic protection, zinc also develops a protective patina when exposed to the atmosphere. Zinc, like all metals, corrodes when exposed to the air. Over time, it forms dense, adherent corrosion by-products as it is exposed to the natural wet and dry cycles of the atmosphere. These by-products, collectively known as the zinc patina, create a tightly adherent, insoluble protective layer on the surface of the zinc coating, lowering the overall corrosion rate. When the zinc patina is fully developed, the zinc will corrode 10 to 100 times slower than the rate of ferrous materials in the same environment.

There are seven zinc coatings commonly used in construction. Four of these—continuous sheet galvanizing, mechanical plating, electrogalvanizing, and zinc plating—can only be used on small parts such as fasteners, or sheet, strip, and wire. The other three—batch hot-dip galvanizing, metallizing, and zinc-rich paints—have much broader applications, but are predominantly used in structural steel applications.

Batch hot-dip galvanizing

Batch hot-dip galvanizing, also commonly called general galvanizing or just hot-dip galvanizing, produces a zinc coating by completely immersing the iron or steel product in a bath (kettle) of molten zinc. Prior to being dipped in the bath, the steel is chemically cleaned to remove organic contaminants, mill scale, and oxides. The final cleaning step also leaves a protective layer of zinc chloride on the surface to prevent oxidation before immersion in the kettle. This layer will evaporate from the surface when the steel hits the top of the bath, which consists of at least 98 percent pure zinc heated to approximately 443 C (830 F).

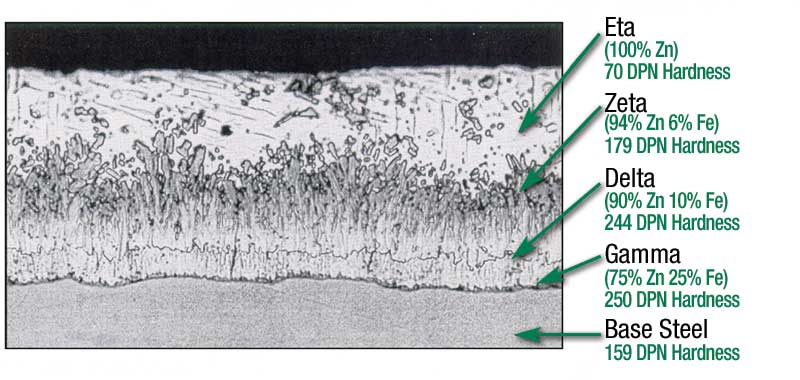

While the steel is in the galvanizing kettle, the zinc metallurgically reacts with the iron to form the hot-dip galvanized coating. This coating consists of a series of zinc-iron alloy layers and a surface layer of pure zinc. These intermetallic layers are tightly bonded (24,281 kPa [3600 psi]) to the steel, becoming an integral part of it rather than just a surface coating. The zinc-iron alloy layers are also harder than the base material, providing excellent abrasion resistance.

Another unique characteristic of batch hot-dip galvanized coatings is its uniform, complete coverage. During the diffusion reaction in the kettle, the intermetallic layers grow perpendicular to all surfaces, ensuring edges, corners, and threads have coating thicknesses equal to or greater than flat surfaces. Additionally, because hot-dip galvanizing is a total immersion process, all interior surfaces of hollow structures and difficult to access recesses of complex pieces are also coated. While the steel articles are in the zinc bath, they float, move, and vibrate around to ensure areas where the steel is in contact with racks or wires are able to be coated. However, it is common to see cosmetic marks when the steel is withdrawn from the galvanizing kettle, but these can be touched up for aesthetic purposes.

The governing specifications for the hot-dip galvanized coating are:

- ASTM A123, Standard Specification for Zinc [Hot-dip Galvanized] Coatings on Iron and Steel Products;

- ASTM A153, Standard Specification for Zinc Coating [Hot-dip] on Iron and Steel Hardware; and

- ASTM A767, Standard Specification for Zinc-coated [Galvanized] Steel Bars for Concrete Reinforcement.

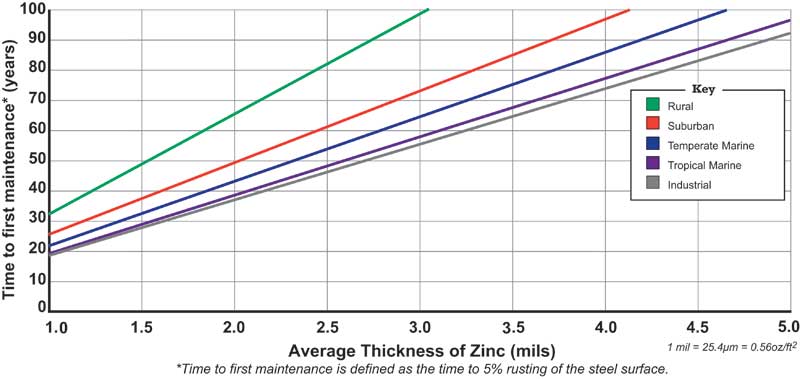

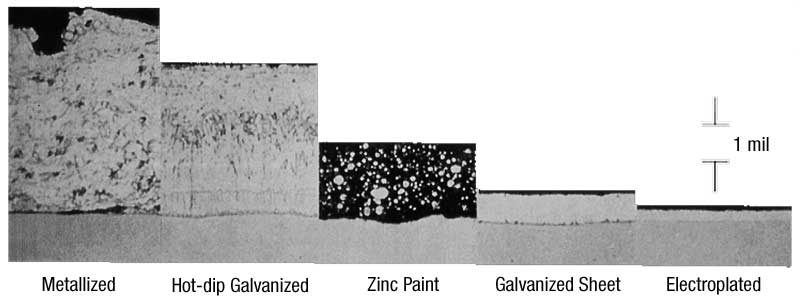

These standards contain minimum coating thickness requirements based on steel type and thickness. The hot-dip galvanized coating is thicker and/or denser than other zinc coatings. The Time to First Maintenance (TFM) chart shows the linear relationship between zinc coating thickness and maintenance-free service life in atmospheric exposure. For example, ASTM A123 requires structural steel that is 15 mm (5⁄8 in.) thick or greater to have a minimum coating thickness of 0.1 mm (3.9 mils). In an industrial environment, this would provide a TFM of 72 years.

Hot-dip galvanizing is used in myriad applications, from electric utility to artistic sculptures, and on

a wide range of sizes from nuts, bolts, and nails to large structural beams and other shapes. Size can be a limitation for batch hot-dip galvanizing, but the average kettle length in North America is 12 m (40 ft), and 16 to 18-m (55 to 60-ft) kettles are common. Employing progressive dipping practices (immersing one portion of a product and then the other) increases the maximum size to nearly one and a half times the bath size. Batch hot-dip galvanizing is most common for protection of atmospherically exposed steel, but it is also frequently used in fresh and saltwater applications as well as embedded in soil and/or concrete.

Zinc spray metallizing

Zinc spraying, or metallizing, is accomplished by feeding zinc powder or wire into a heated gun where it is melted and sprayed onto the steel component using combustion gases and/or auxiliary compressed air. There are automated metallizing processes, but often the coating is still applied by a skilled operator. Prior to metallizing, the steel must be abrasively cleaned to a near white metal. As the steel surface must remain free of oxides, it is common to clean smaller areas, coat the area, and then move to the next section of the part—adding time and cost to the coating process. The coating is 100 percent zinc and is often sealed with a low-viscosity polyurethane, epoxy-phenolic, epoxy, or vinyl resin. Metallizing is most commonly shop-applied, but can also be done in the field.

The metallized coating is rough and slightly porous. However, as it is exposed to the atmosphere, zinc corrosion products tend to fill the pores, providing consistent cathodic protection. The metallized coating can be applied to meet any thickness requirements (with a density of approximately 80 percent of hot-dip galvanizing), but can have adhesion issues if it is excessively thick. The metallized coating cannot be applied to interior surfaces and tends to thin at corners and edges, which are harder to achieve consistent spray thicknesses than flat surfaces.

Zinc spray can be applied to materials of any size, and is often used as an alternative to, or in conjunction with, batch hot-dip galvanizing when a part is too large for immersion in the galvanizing kettle. Metallized coatings are increasing in popularity in the bridge market, as many counties and Departments of Transportation (DOTs) look to meet a 100-year service life for their bridges. Although the coating is more commonly applied in the shop, it is possible to apply in the field, making it a great option for extending the life of a steel structure already in place. The biggest limitations to metallizing applications are availability (skilled operator and/or equipment) and the cost premium.

Zinc-rich paints

Zinc painting, often erroneously called ‘cold galvanizing,’ is the brush or spray application of zinc dust mixed with organic or inorganic binders. Zinc-rich paints typically contain 92 to 95 percent metallic zinc in dry film, and are often coated with other intermediate and/or topcoat paint systems. Prior to the paint application, the steel is blasted to a near white metal (The Society for Protective Coatings Standard SSPC-SP10) or white metal (SSPC-SP5). The zinc dust is mixed with a polymeric-containing vehicle and is constantly agitated during application to ensure a homogenous mixture of zinc and proper adhesion. Zinc-rich paints can be applied in both the shop and the field (if the environmental conditions meet the paint manufacturer’s requirements).

Zinc-rich paint, like all paints, is a surface coating mechanically bonded to the steel at a few hundred pounds per square inch (psi). Both organic and inorganic paints can be applied to varying levels, but potential for cracking increases with thickness. There are some performance differences between inorganic and organic zinc-rich paints. Inorganic formulations can withstand temperatures up to about 371 C (700 F), and do not chalk, peel, or blister readily. Inorganic zinc-rich paints, which have about half the density of zinc per mil as batch hot-dip galvanizing, are easy to weld and provide simpler cleanup than organics. The properties of organic zinc-rich paints depend on the solvent system. Multiple coats can be applied in a short period without cracking. However, organic formulations are limited to temperatures of 93 to 148 C (200 to 300 F) and are subject to ultraviolet (UV) degradation.

Photos © SeanBrecht

Zinc-rich paints can be applied to any size and shape of steel, and are often used as primers to high-performance two- and three-coat systems. They are also widely used for touch-up and repair of hot-dip galvanized coatings. In mild environments, zinc-rich paints can be used independently; however, using them alone in more severe environments may not be advised because the cathodic protection afforded is more limited than other zinc coatings.

Like other zinc coatings, it is possible for zinc-rich paints to provide cathodic protection, but in order to do so, it is critical to have zinc dust in high enough concentrations to provide for conductivity between the zinc particles and the steel. There is some question about the cathodic capabilities when the particles are encapsulated in the binder and the binder is non-conductive.

Continuous sheet galvanizing

Continuous sheet galvanizing is a hot-dip process similar to batch galvanizing, but it is only applied to steel sheet, strip, or wire. It is a coil-to-coil process where steel sheet from 0.2 to 43.8 mm (0.01 to 1.7 in.) thick and up to 1828 mm (72 in.) wide is passed as a continuous ribbon through cleaning baths and the molten zinc at speeds up to 183 m (600 ft) per minute. Prior to coating, the continuous sheet is cleaned, brushed, rinsed, and dried. Then, the steel passes into the heating or annealing furnace to soften it and impart the desired strength and formability. While in this furnace, any oxides on the surface are also removed, so it is clean before dipping in the molten zinc bath. As the sheet is withdrawn from the bath, precisely regulated, high-pressure air (known as an air knife) is used to remove any excess zinc to create a closely controlled coating thickness.

Photos courtesy AGA

There are a number of different sheet products produced in this process including:

- galvanized;

- galvannealed;

- two alloys of zinc and aluminum;

- two aluminum based alloys; and

- the terne coating.

Since the process is very similar to batch hot-dip galvanizing, the two coatings are often confused. The major difference is found in the zinc coating thickness. The continuous sheet process has greater control and precision of the zinc coating thickness, and the coating itself is mostly unalloyed zinc, though minimal alloy layers are present. Another key difference is the coating in this process is applied prior to fabrication, whereas batch hot-dip galvanizing is applied after.

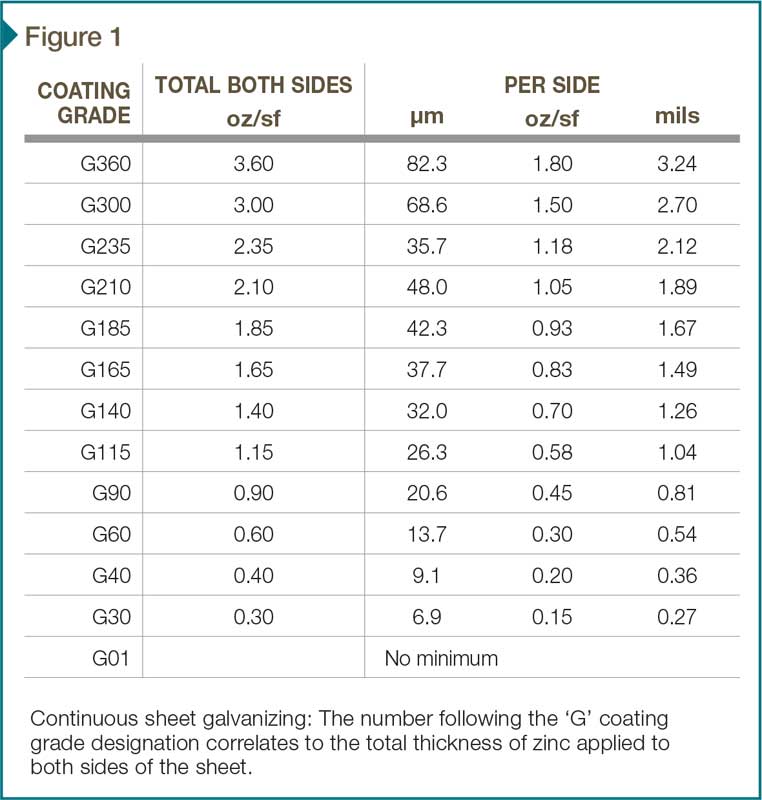

Continuous sheet galvanizing is stocked in a variety of coating weights. One of the most common is Class G90 which has 274 g/m2 (0.9 oz/sf) of zinc (total both sides) or about 0.8 mils (20.6 µm) per side. Figure 1 lists available coating grades of continuous sheet galvanizing.

Continuous sheet galvanizing is most commonly used in car bodies, appliances, corrugated roofing, siding, and ductwork. The final coating is very smooth, allowing for it to be treated for painting. Most continuous sheet galvanizing is specified for indoor applications or where exposure to corrosive elements is mild. Some formulations including other alloys in addition to or besides zinc may be suited for other applications.

Electrogalvanizing

Electrogalvanized (electroplated) coatings are created by applying zinc to steel sheet and strip by electro-disposition. Similar to sheet galvanizing, the operation, often done in a steel mill, is continuous and the coating thickness is minimal. Prior to coating, the sheet or strip is fed through a series of washes and rinses, then into the plating bath. The coating develops as positively charged zinc ions in the solution are electrically reduced to zinc metal and deposited on the negatively charged cathode (sheet steel).

The coating is a highly ductile, thin layer of pure zinc, tightly adherent to the steel. The coating weight ranges from 61 to 152 g/m2 (0.2 to 0.5 oz/sf) for sheet products. The coating is thinner and smoother than the continuous sheet galvanized coating. The most common applications are in automobile and appliance bodies. The electrogalvanized coating can be treated with a wash primer, which leaves a passivation layer as well as cleans and etches the surface to make it suitable for painting.

Mechanical plating

Mechanical plating is accomplished by tumbling small parts in a drum with zinc, proprietary chemicals, and glass beads. The beads peen zinc powder on to the part, and the parts are then dried and packaged. Sometimes, the parts are then post-treated with a passivation film before being dried and packaged. Mechanical plating is limited to small iron and steel parts, typically no larger than 203 to 228 mm (8 to 9 in.) and weighing less than 0.45 kg (1 lb). Before placed in the plating barrel, the parts are cleaned and flash copper-coated.

The zinc coating thickness of mechanically plated parts ranges from 0.2 to 4.3 mils (5 to 109 µm), but the common thickness on commercial fasteners is 2 mils (50 µm). The thickness is regulated by the amount of zinc in the barrel and the duration of the tumbling time. The coating is mechanically bonded to the surface and the density is about 70 percent that of hot-dip galvanized coatings.

Mechanical plating is most commonly used on high-strength fasteners and other small parts unsuitable for hot-dip galvanizing. The coating application process will cause complex designs with recesses or blind holes to have inconsistent or non-existent coatings because the glass beads either cannot access the area to apply the zinc, or cannot peen with enough velocity to coat the surface consistently.

Zinc plating

Zinc plating is identical to electrogalvanizing in principle, as the coating is electro-deposited. However, zinc plating is used on small parts such as fasteners, crank handles, springs, and other hardware items rather than sheet metal. After alkaline or electrolytic cleaning and pickling to remove surface oxides, steel parts are loaded into a barrel, rack, or drum and immersed in the plating solution. Various brightening agents may be added to the solution to add luster.

The coating is a thin, pure layer of zinc with a maximum thickness of 25 µm (1 mil). The specification ASTM B633, Standard Specification for Electrodeposited Coatings of Zinc on Iron and Steel, lists four classes of zinc plating: Fe/Zn 5, Fe/Zn 8, Fe/Zn 12, and Fe/Zn 25, where the number indicates the coating thickness in micrometers (µm). Typically, zinc-plated coatings are dull gray with a matte finish, but whiter, more lustrous coatings can be produced depending on agents added to the plating bath or through post-treatments. Zinc plating is usually only used for interior or mildly corrosive conditions on fasteners, light switch plates, and other miscellaneous small parts.

Selection of zinc coatings

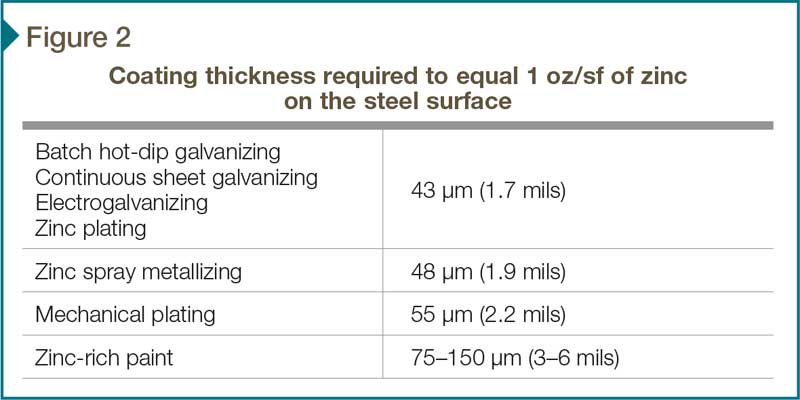

The architect, engineer, or specifier must evaluate the service environment, desired life, and initial lifecycle costs before determining the zinc coating best-suited for the project. Each zinc coating provides varying degrees of corrosion protection in a given exposure environment. The life of all zinc coatings is linear to the zinc coating thickness. However, zinc coating thickness cannot be evaluated without also considering the density, or zinc per unit volume. The zinc coating application process will dictate both the density and the thickness.

To compare the various zinc coatings, it is easier to convert all the coatings into an equal weight per unit area of zinc, which in theory would provide equal service lives. Figure 2 represents the coating thickness required by each zinc application method to equal 305 g/m2 (1 oz/sf) of zinc on the surface. So, according to the conversions, 1.7 mils (43 µm) of hot-dip galvanizing would give the same service life as 2.2 mils (43 µm) of mechanical plating, etc.

Conclusion

There are many ways zinc can be used to protect steel from corrosion. However, lumping all of these zinc coatings under the umbrella term ‘galvanizing’ is unfair, as each is very different in application, characteristics, and performance. Once a specifier evaluates the exposure condition of a project, he or she can select the zinc coating best-suited for that particular application, because not all zinc coatings are created equal.

Melissa Lindsley is the marketing director for the American Galvanizers Association (AGA), and educates architects, engineers, fabricators, owners, and other specifiers about the technical aspects and benefits of hot-dip galvanizing. Lindsley can be reached via e-mail at mlindsley@galvanizeit.org[1].

- mlindsley@galvanizeit.org: mailto:mlindsley@galvanizeit.org

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/are-all-zinc-coatings-created-equal/