Information courtesy AIA and EJCDC

What constitutes the contract documents?

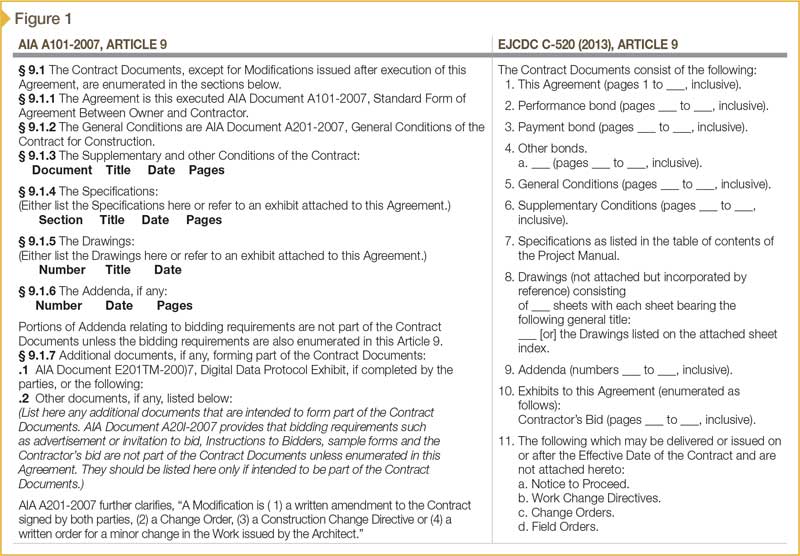

AIA A101-2007 Article 9 and EJCDC C-520 (2013) Article 9 each offer listings defining the contract documents, as presented in Figure 1. A notable difference between the AIA’s and EJCDC’s standard enumerations of the contract documents is that the AIA’s model language does not explicitly include performance and payment bonds as contract documents. However, there are also some common themes between the two. For instance, both the AIA and EJCDC offer specific indication of the exact extent of each contract document, including the number of pages for each, the individual specifications sections, and the extent of the drawings. Neither leaves what constitutes ‘drawings’ and ‘specifications’ unspecific.

Further, neither includes documents comprising the bidding requirements, which typically apply only to the bidding or procurement process but are not applicable after the contract is fully signed by the parties and made effective. The exception to this is that EJCDC allows, via optional language, inclusion of the contractor’s bid—typically only the list of bid items with their associated pricing—as an exhibit to the agreement for contracts that have numerous bid items. EJCDC includes such optional language primarily to reduce the potential for transcription errors when drafting the final owner-contractor agreement for signature. Contracts with numerous bid items are common in civil/sitework, where there are often many unit price items.

It is incumbent on the person preparing the final contract documents for signature, usually after the bids are opened and the contract is awarded, to carefully complete Article 9 of the owner-contractor agreement, and to ensure all required contract documents are properly and fully enumerated therein.

Correspondingly, when the final contract documents are assembled for signature by the parties, they should not include extraneous documents such as the bidding requirements (e.g. advertisement or invitation to bid, instructions to bidders, bid form, bid bond, or other bid form supplements). It is also important to delete such items from the project manual’s table of contents before finalizing the contract documents for signature.

What should not be contract documents?

It is tempting to worry only about what the contract documents are, but one should also be aware that confusion on these items is common. For clarification, the following should not be considered or indicated as contract documents:

- bidding requirements, as discussed earlier in this article;

- reports and drawings characterizing the site, such as soil boring logs, geotechnical engineering reports, drawings of existing conditions and record drawings, and reports of hazardous materials at the site (the reasons why such items should not be contract documents will be addressed in a future article);

- permits obtained by the owner, because any such permits—with which the contractor must comply—should be explicitly and clearly written into the specifications (merely binding in a lengthy regulatory permit may introduce unnecessary requirements inapplicable to the contractor, which could create confusion and conflicts with other contract documents);

- evidence of insurance submitted by the parties (e.g. insurance certificates and endorsements) that are prepared neither by the parties to the contractor nor the design professional, as they may contain provisions conflicting with the insurance requirements of the contract documents—rather, insurance certificates and endorsements serve only to indicate how the parties propose to comply with insurance requirements of the contract;

- shop drawings and other contractor submittals, which typically contain a much greater level of detail than the contract documents, may conflict with the contract documents, and are not prepared or sealed by the owner’s design professional—similar reasoning applies to contractor-generated coordination drawings;

- correspondence and meeting minutes; and

- RFIs and associated responses from the design professional, because these documents merely clarify what the contract documents already say, and should not be used to attempt to change the contract’s requirements. Each RFI response that addresses a change to the contract’s requirements should be accompanied by an associated contract modification, such as a change order/directive or field order/architect’s supplemental constructions.

Excellent article! Very well written.