Photo © BigStockPhoto

Vaguely defined contract documents

This author has reviewed more than 100 owners’ non-standard construction documents, and has encountered many definitions of contract documents that are too vague to be effective, and which therefore increase the owner’s risk.

An example of undesirable vagueness from one such contract is, “the Contract Documents…include all exhibits, attachments, supplements, and all other such documents used as contract modifications.”

It could take opposing lawyers a very long time to argue various interpretations of such a provision.

Another problem frequently observed by this writer is requiring blanket compliance with referenced documents such as state or provincial Department of Transportation (DOT) standard specifications, but not indicating them in full or in specific part as contract documents. (This does not refer to compliance with cited reference standards such as ASTM or ANSI standards. Rather, multiple contracts reviewed by this author require blanket compliance with all associated state DOT standard specifications or similar regional or local standards.) Requiring such compliance with a comprehensive set of third-party documents—which often have their own general conditions-type provisions—may create contractual nightmares full of fatal contractual flaws. Figuring out which requirements apply in any resulting claims will take a long time, a lot of money, and the involvement of several lawyers and arbitrators.

This author has also observed a relatively prevalent practice of including ‘appendices’ in construction project manuals—perhaps as a means of adding information that the design professional does not otherwise know where to place. While appendices appear in construction documents, this author has never seen them listed in the owner-contractor agreement (or elsewhere) as being part of the contract documents. Are they a contractual obligation? That may be for a jury or arbitration board to decide, unless design professionals can avoid such vagueness when drafting the construction documents.

Image courtesy Arcadis

Avoiding mixing up the terms

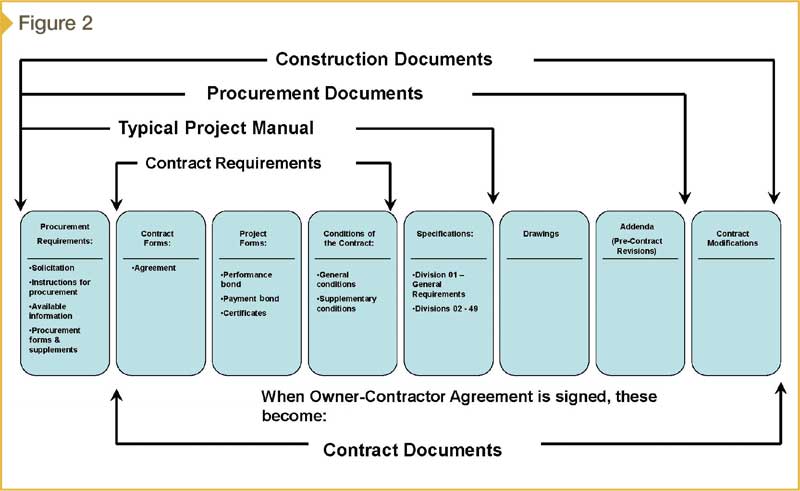

It can be easy for project stakeholders to mix up terms such as ‘contract documents,’ ‘bidding documents,’ ‘construction documents,’ and ‘specifications.’ However, these are not interchangeable. Misusing such terms in the contract documents can have important ramifications—which most people do not want to learn from the contractor’s attorney. This is presented fairly well in Figure 2.

EJCDC C-700 (2013) defines various terms at Paragraph 1.01 A, including:

Bidding Documents—The Bidding Requirements, the proposed Contract Documents, and all Addenda …

Bidding Requirements—The advertisement or invitation to bid, Instructions to Bidders, Bid Bond or other Bid security, if any, the Bid Form, and the Bid with any attachments …

Contract Documents—Those items so designated in the Agreement, and which together comprise the Contract …

Drawings—The part of the Contract that graphically shows the scope, extent, and character of the Work to be performed by Contractor …

Specifications—The part of the Contract that consists of written requirements for materials, equipment, systems, standards, and workmanship as applied to the Work, and certain administrative requirements and procedural matters applicable to the Work.

The definition of ‘Specifications’ does not include contract requirements such as the owner-contractor agreement, contract bonds, general conditions, or supplementary conditions; thus, such documents are not ‘Specifications.’

Note in the following definition from EJCDC C-700 (2013), ‘Shop Drawings’ are specifically not part of the contract documents:

Shop Drawings—All drawings, diagrams, illustrations, schedules, and other data or information that are specifically prepared or assembled by or for Contractor and submitted by Contractor to illustrate some portion of the Work. Shop Drawings, whether approved or not, are not Drawings and are not Contract Documents.

Another useful definition from EJCDC C-700 (2013) is:

Project Manual—The written documents prepared for, or made available for, procuring and constructing the Work, including but not limited to the Bidding Documents or other construction procurement documents, geotechnical and existing conditions information, the Agreement, bond forms, General Conditions, Supplementary Conditions, and Specifications. The contents of the Project Manual may be bound in one or more volumes.

The AIA’s standard contract documents include definitions of most of the above terms, using language very similar to EJCDC’s. For corresponding AIA definitions, see AIA A101, AIA A201, and AIA A701, Instructions to Bidders.

Conclusion

It is crucial to indicate what constitutes the contract documents completely and clearly, and at only one location—preferably, the owner-contractor agreement. Owners and design professionals need to be cognizant of this matter, and properly draft the associated provisions. Failure to do so can mean unpleasant encounters with attorneys and significant embarrassment.

Kevin O’Beirne, PE, FCSI, CCS, CCCA, is a principal engineer and manager of standard construction documents at Arcadis in Buffalo, New York. He is a professional engineer licensed in New York and Pennsylvania, with 30 years of experience designing and constructing water and wastewater infrastructure. O’Beirne is an active member and past national chair of the Engineers Joint Contract Documents Committee (EJCDC), and is a member of CSI’s MasterFormat Maintenance Task Team. He can be reached at kevin.obeirne@arcadis.com.

Excellent article! Very well written.