Avoiding galvanic corrosion with dissimilar metals

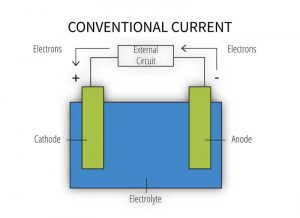

The formation of a galvanic cell (Figure 2) requires the presence of all the following components:

- anode – metal of greater negative electrical potential, where electrons are generated by the reaction (accelerated corrosion occurs here);

- cathode – metal of less negative electrical potential, where electrons are received (this metal is protected from corrosion);

- electrical connection – such as direct contact between the anode and cathode; and

- electrolyte – conductive medium allowing electrons to be transferred from the anode to the cathode (e.g. exposure to humid atmospheric conditions, moist soil, or common moisture such as water, rain, dew, snow, condensation, or sea spray) (for more information, read Galvanic Corrosion, Metals Handbook [ninth edition] by Robert Baboian).

When any one of these components is absent, galvanic corrosion cannot occur. Similarly, the risk of galvanic corrosion is considered negligible for sheltered conditions such as the interior of climate-controlled buildings, or very low for structures located in arid climates and atmospheric conditions of low corrosivity.

Rate of galvanic corrosion for galvanized steel

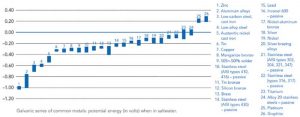

If the potential for galvanic corrosion is present on the project due to the use of galvanized steel with other metals, various factors can influence the rate of accelerated corrosion. These factors may or may not result in conditions considered tolerable in service. Zinc tends to be high on the galvanic series of metals in various electrolytes, meaning the HDG coating is anodic to most other metals. The galvanized coating will not only sacrifice itself to protect the underlying base steel, but also try to protect other connected metals such as copper, stainless steel, carbon steel, and aluminum. This will lead to a more rapid consumption of the zinc coating, and decrease the overall longevity afforded. Generally, the corrosion rate increases when combining galvanized steel with metals farther and farther away from zinc in the galvanic series (Figure 3).

The aggressiveness of the electrolyte or installation environment can also impact the severity of corrosion. In many atmospheric applications, rainwater and dew are the primary electrolytic materials, but they do not contain many salts and ions, which would make them highly conductive. Alternatively, industrial and marine environments make strong electrolytes because they contain a heavy amount of salts and ions. Even within a single building structure there may be different degrees of exposure to electrolytes of varying strength, such as a building situated near a coastline receiving regular ocean spray to only one face.

However, the corrosion rate is also influenced by the surface area ratio of the different metals. A high zinc corrosion rate can be reduced if the combination of a small area of galvanized steel with a large area of cathodic metal is avoided. Where applicable, a zinc-to-metal surface ratio of at least 10:1 is helpful to minimize the impact of galvanic corrosion on galvanized steel members (read “Opposites Attract: A Primer on Galvanic Corrosion of Dissimilar Metals,” by Christopher Hewitt, Alan Humphries, and Eric Twomey). For example, specifying stainless steel fasteners to join HDG steel framing may be considered, while the use of galvanized fasteners to combine cathodic metals such as carbon steel, copper, or stainless steel should be avoided.

The rate of galvanic corrosion may also be affected by the presence of metal oxide layer formation, the use of corrosion inhibitors, chemical reactions, physical and chemical homogeneity of the metal surfaces, and other environmental effects (temperature, oxygen content, effect of electrode potential, etc.) (for more information, read Galvanic Corrosion, Metals Handbook [ninth edition] by Robert Baboian and also read Galvanic Corrosion of Zinc and It’s Alloys by X.G. Zhang). As galvanic corrosion is a very complex issue, it can be difficult to predict the suitability of the various metals in direct contact with HDG steel. To assist the specifier, the American Galvanizers Association (AGA) offers some guidance (Figure 4) through the interpretation of available corrosion data to predict the impact of galvanic corrosion on HDG coatings based on a limited set of variables (electrical potential, environment, and surface area ratio) (consult Additional Corrosion of Zinc and Zinc Based Alloys Resulting From Contact With Other Metals or Carbon by the British Standard Institute, MIL-STD-889C, Department of Defense Standard Practice: Dissimilar Metals [22-AUG-2016], and American Iron and Steel Institute’s Committee of Stainless Steel Producers, April 1977).