Guidelines and sensitivity to noise

Of course, not all building types are equally sensitive to noise, as is suggested by the higher absolute limits allowable in commercial and industrial zones. Noise sensitivity, however, is not limited to residential buildings. Occupants of commercial offices are often quite sensitive to intrusive outside noise. For example, guidelines published in the American Society of Heating and Refrigerating Engineers (ASHRAE) 2015 HVAC Applications Handbook suggest executive suites and conference rooms in commercial office buildings be designed for interior sound levels of 30 to 35 dBA. It can be difficult to achieve these levels in the vicinity of nearby external noise sources using conventional curtain wall designs.

Institutional building types, including hospitals, nursing homes, courthouses, schools, and libraries, are usually limited to 30 to 35 dBA, and luxury residential buildings will typically target an interior background noise level of 30 dBA. Traffic, train, and aircraft noise sources must be considered in the design of these building types, recognizing the lower the required interior background noise levels, the more robust the exterior envelope of the building must be to avoid intrusion of exterior noise.

Noise mitigation in building construction

Reducing indoor perception of exterior noise requires introduction of a barrier of some kind between the source and the building occupants. Although it is sometimes possible to orient or locate a building in such a way as to take advantage of external sound barriers (e.g. highway barrier walls, earth berms, or shielding from other buildings), it is more often entirely up to the materials comprising the outer skin of the building to provide sufficient impediment to the noise transfer.

As a first step, whenever possible, one should take advantage of barriers, earth berms, and even building features such as lower-level balconies on a multi-story condo, to break up the line of sight between an exterior source and a sound-sensitive building interior. Simply eliminating direct line-of-sight to a problem noise source can usually provide a significant reduction in sound transfer.

Although the intrusion of exterior noise is highly dependent on the surface mass of the exterior wall construction, when outdoor noise enters a building, it is always reduced somewhat, even if the building has open windows or air vents. The amount of that reduction depends on several factors, including the wall construction, the amount and thickness of the glazing, the ratio of window to wall area, the amount of open window area, and the amount of acoustically absorptive interior finish treatment. Further, the audibility of an intruding noise also depends on the existing interior background sound level. As a general rule, if the intruding noise can be reduced to approximately 5 dB below the existing background noise level, it will likely not be cause for complaint.

For example, whereas a windowless masonry wall may have an OITC 50, introduction of a single window with an area of one fourth of the wall can reduce that performance to OITC 29. Of course, a couple of principles apply. For example, the heavier the masonry, and the fewer windows, the more effective a wall is at reducing exterior sound. There are, however, limits to the performance of monolithic barriers, as significant improvement in performance generally requires doubling the mass of the wall.

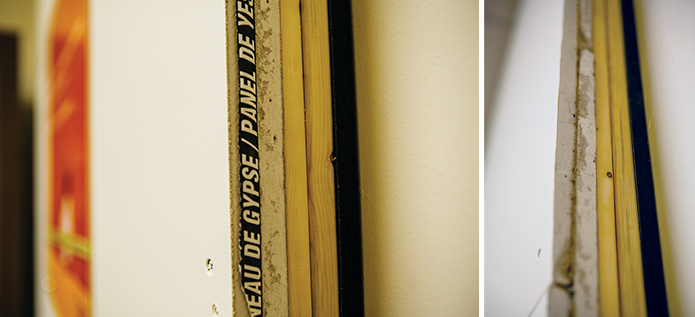

Larger increases in OITC performance of a wall can be achieved by incorporation of a secondary interior wall decoupled and separated from the outer wall by an insulated air space. Additionally, the choice of insulation is important. Closed-cell foam insulation materials are not sound-absorbing, and do not improve sound isolation of wall assemblies. Sound-absorbing insulation materials, such as glass fiber, open-cell foam, mineral wool, and cellulose are effective for sound isolation in all partition assemblies.