Air barrier baseline

Beyond safety considerations, the three primary criteria for specifying liquid air barriers are aimed at providing value for owners by reducing building energy requirements and operating costs, including maintenance.

Air leakage

Testing provides an indicator of air permeance (i.e. the rate of air leakage through a material). An air barrier material must achieve air leakage of less than 0.002 L/(s • m2) @ 75 Pa (0.004 cfm/sf @1.57 psf), per ASTM E2178, Standard Test Method for Air Permeance of Building Materials. In the field, a liquid air barrier consists of both the primary air barrier material and components such as primed and self-sealing tapes and adhesives, which comprise the air barrier assembly. Board and sheet materials may also use tapes, adhesives, or foams. However, they require additional labor for sealing board-to-board seams, fasteners, and structural transitions, and these details add to the potential for air infiltration.

Air barrier assemblies are usually tested in accordance with ASTM E2357, Standard Test Method for Determining Air Leakage of Air Barrier Assemblies. The entire assembly is tested in three phases—positive and negative air pressure, then simulated wind gusts up to 159 km/hr (99 mph). As the entire system is under test, the maximum leakage permitted is 10 times higher than for the material alone. The test specifies a maximum air leakage not to exceed 0.02 L(s • m2) (0.04 cfm/sf) under a pressure differential of 75 Pa (1.57 psf). ABAA supports the data from ASTM E2357, which is the most critical information available to the designer when determining air leakage.

Air barrier assemblies can pass ASTM E2357 with any one of three types of test walls or test assemblies:

- opaque wall;

- continuity at penetrations; or

- foundation interface at opaque wall (with modifications).

The second is the most difficult, because it includes any penetrations around vertical and horizontal joists, junction boxes, masonry ties, and a window opening. This makes the second test wall highly important, though not all liquid air barrier assemblies will use it to qualify or can do so in a single coat. (More than 1.8 to 1.95 mm [60 to 65 wet mils] usually indicates more than one coat.)

Weather resistance

Some air barrier materials also act as water or weather barriers. Under ASTM E331, Standard Test Method for Water Penetration of Exterior Windows, Skylights, Doors, and Walls by Uniform Static Air Pressure Difference, test assemblies should remain watertight. Assembly enclosures are tested with the inside air pressure 299 Pa (6.24 psf) lower than outside and a continuous water flow rate of 29 L/hr/m2 (5 gal/hr/sf). This simulated downpour is equivalent to 2 m (8 ft) of rain per hour.

Weather tests can also simulate wind conditions, as does ASTM E2357. High sustained winds can lift cladding and underlying insulation boards or barrier sheathing—especially those not fully adhered—and expose exterior walls to the full force of a storm. Of course, fluid-applied air barriers are not subject to wind uplift when applied directly to block or other solid-surface walls, and are frequently specified for these particular applications.

Vapor permeance

Water vapor can get trapped inside the cavity of new masonry foundation walls, or moisture from the air can condense inside exterior wall construction layers. New wall assemblies are generally insulated and covered with some combination

of plywood or oriented strand board (OSB), glass-faced sheathing, polyethylene film, or other sheet or sheathing material, plus a separate air barrier. Moisture trapped inside the cavity or interior wall materials can cause mildew or serious mold conditions. Vapor-permeable air barriers allow water vapor to escape through controlled diffusion.

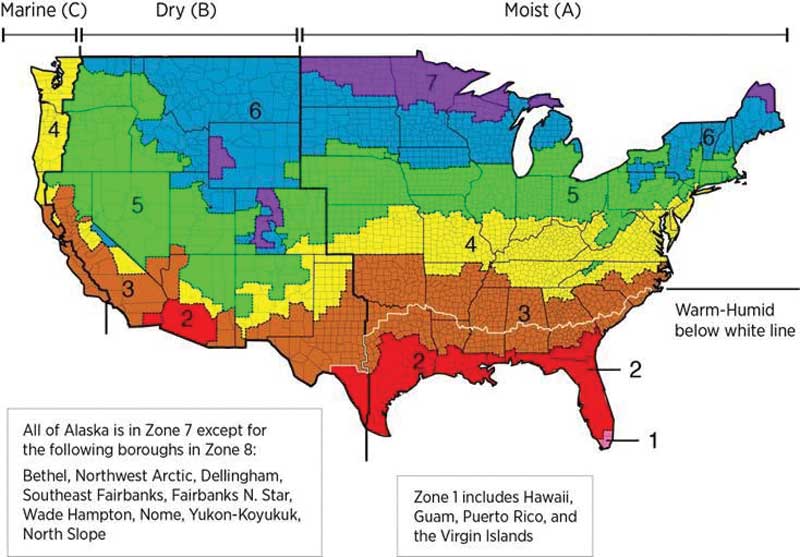

Moisture condensation can pose an issue in both warm and cold climate zones with even moderate humidity because of the wide temperature differential between inside and outside air. Trapped moisture tends to condense on the warmer side of a material. In warm, moist areas of the country, though, the exterior wall assembly is quite different. For example, Climate Zones 1 to 3 do not require any class of vapor retarder on the interior surface of insulation in insulated wall assemblies (Figure 3).