There are three general classes of vapor retarders:

- Class I, rating 0.1 perm or less;

- Class II, rating 1.0 perm or less and greater than 0.1 perm; and

- Class III, rating 10 perms or less and greater than 1.0 perm.

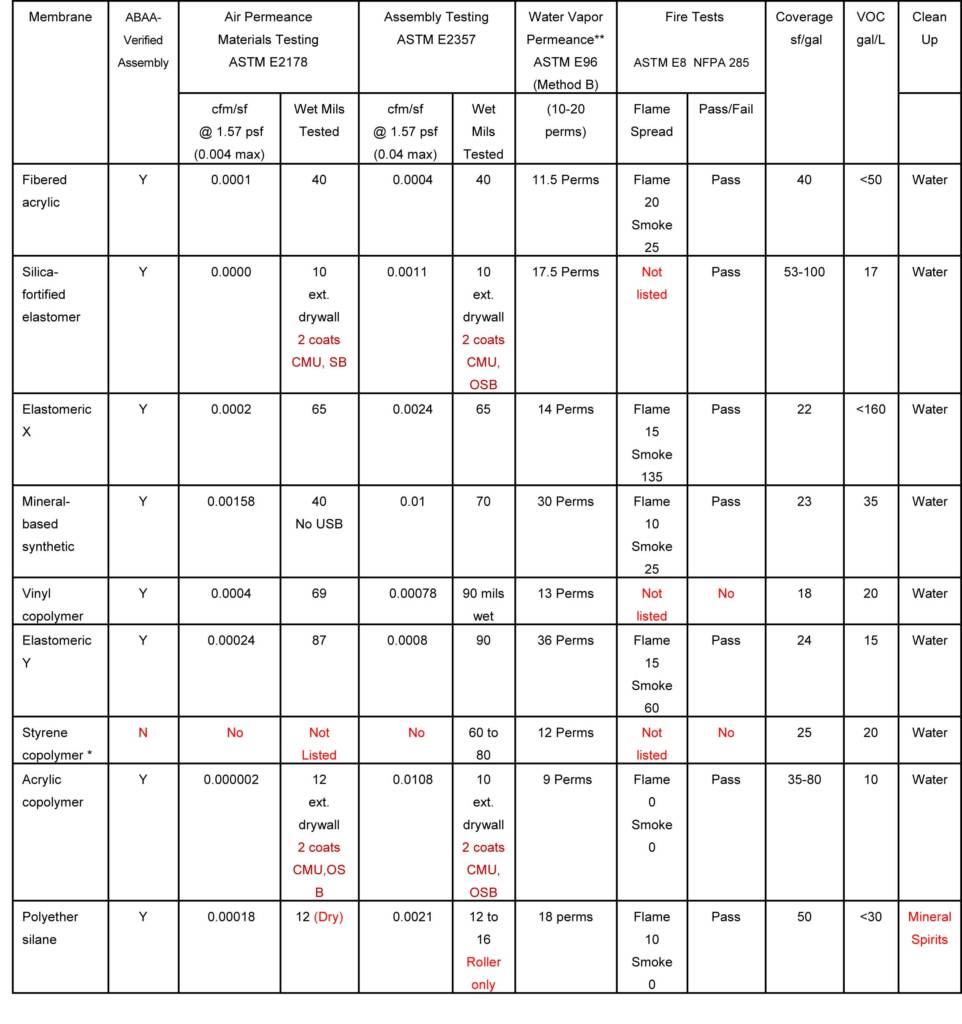

IBC and IECC define vapor retarders as having a water vapor permeance of 1 perm or less when tested in accordance with ASTM E96, Standard Test Methods for Water Vapor Transmission of Materials. (Diane Hun et al’s study, “Air Leakage Rates in Typical Air Barrier Assemblies,” was published by Oak Ridge National Laboratory [ORNL] and the U.S. Department of Energy [DOE] last November.) However, a higher level of vapor permeance is generally desired in an air barrier. ABAA recommends air barriers in the 10- to 20-perm range to permit vapor transmission out of building materials. This is because large amounts of air movement can bring large amounts of moisture (Figure 4).

Water vapor condensation happens when materials used in the envelope are ineffective at controlling air infiltration and exfiltration due to many cracks or high permeance to air. The air entry point and exit point are often distant from each other, giving the moisture-laden air enough time to cool below its dewpoint and condense on colder surfaces within the enclosure assemblies, causing IAQ problems, mold growth, corrosion, rot, and premature failure of the building enclosure.

High relative humidity (RH) affects the overall vapor transmission through a material and in the direction of the drier air. When it is warm outdoors, moisture tends to migrate toward dry conditioned air inside. In cold outdoor temperatures, higher vapor pressure from the warm air inside a building tends to push vapor outward. There are two ASTM E96 test methods performed at standard temperature. Method A (dry) uses a dessicant inside a cup sealed with the material under test, and Method B (wet) uses distilled water in the sealed cup. Both can be useful for understanding how a vapor-permeable membrane performs under different humidity conditions.

Generally, air barriers that can cost-effectively meet ABAA-recommended vapor permeance in the field should be the basic project performance goal. For this reason, some project specifications require a minimum of 1.2 mm (40 mils) to achieve desired crack bridging and other film properties. Thinner barrier films may not achieve continuous coverage, and if a second coating is required, that doubles the cost of materials and labor—and also reduces actual vapor permeance. At the other extreme, liquid air barriers requiring more than about 1.8 mm (60 mils) to achieve rated properties are more likely to slump during application, and are typically applied in two thinner coats to achieve total mil thickness. Medium-mil products (i.e. those ranging 0.9 to 1.5 mm [30 to 50 mils]) can be applied in one pass, saving labor costs.

Figure 4 summarizes baseline specifications for several different types of liquid air barriers. Figure 1 lists these and other test performance standards that are often important in the final selection. Pull tests should be performed on different substrates per ASTM D4541, Standard Test Method for Pull-off Strength of Coatings Using Portable Adhesion Testers, Method E, and those results should be part of the application criteria. It is important to always check with the manufacturer to determine compatibility of products that will be used with the air barrier system.