Building Envelope Workhorses: The growing role of fluid-applied air barriers

by Katie Daniel | November 10, 2017 3:25 pm

[1]

[1]by James Arnold, PE, RRO, and Lynn Walters

According to the Air Barrier Association of America (ABAA), there are seven different categories of air barrier assemblies. (These categories are self-adhered sheet membranes, fluid-applied membranes, sprayed polyurethane foam [SPF], mechanically fastened commercial building wrap, board stock/rigid cellular thermal insulation board, factory-bonded membranes to sheathing, and adhesive-backed commercial building paper. For more, consult Diane Hun’s “New Air- and Water-resistive Technologies for Commercial Buildings[2].”) Each offers advantages depending on a number of factors, including geography, labor considerations, and even the height of the structure. This article examines the growing role of fluid-applied air barrier systems in meeting code and test specifications, and discusses related approaches and pitfalls. It also reviews common architectural details that present air barrier challenges, as well as fluid-applied assemblies that can address them.

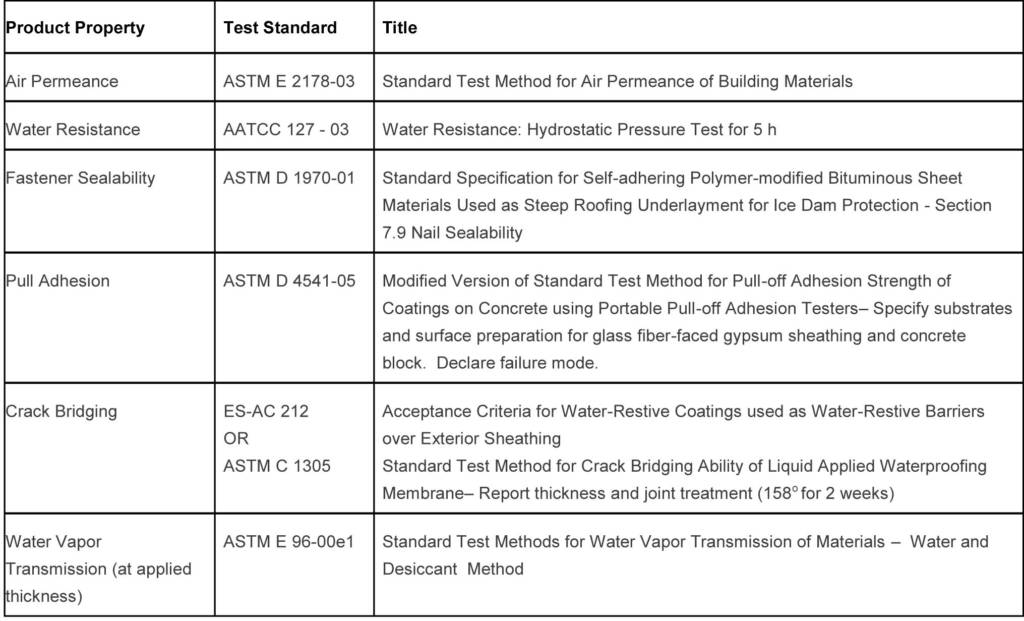

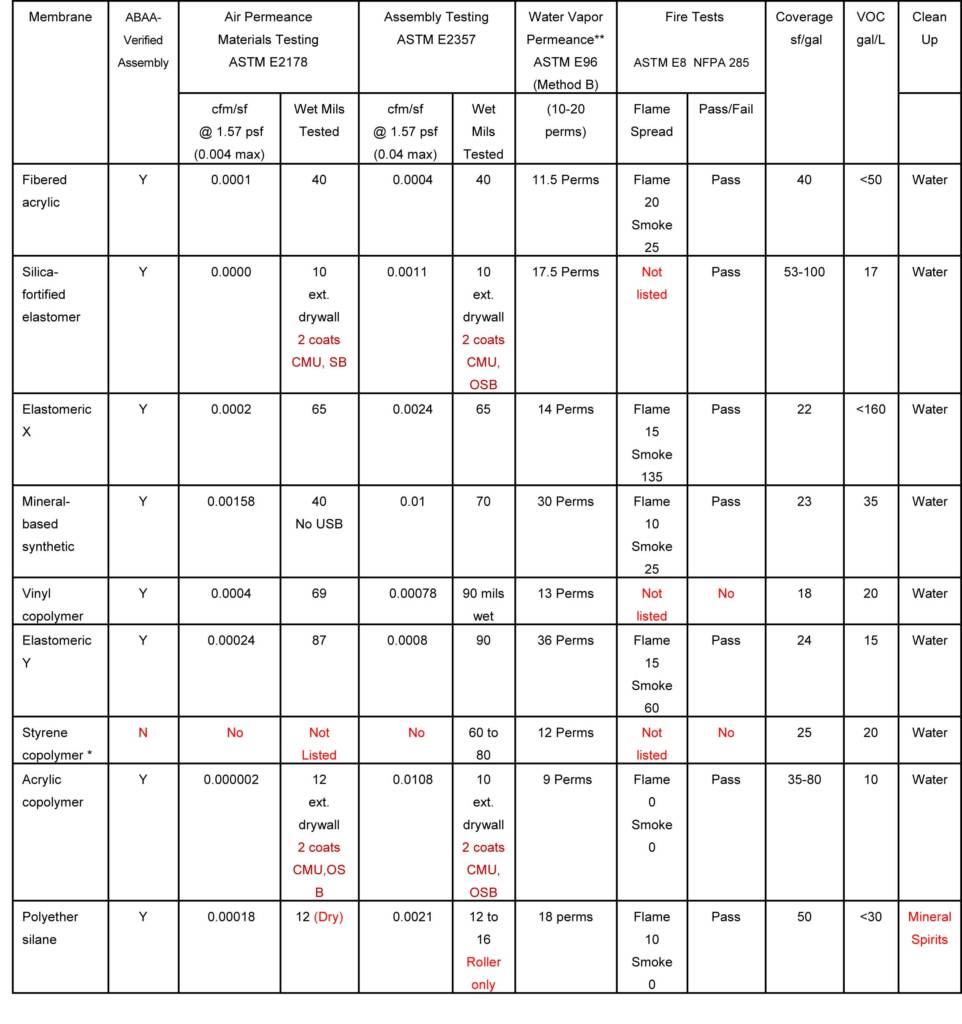

While there is no one-size-fits-all solution, fluid-applied air barriers are growing in acceptance because of their ease of application and versatility across a range of code and performance requirements. Indeed, there are a plethora of commercial air barriers on the market, and it can be difficult to distinguish between products simply by identifying which comply with test code requirements. Specifications between products can vary widely, and ABAA establishes minimum standards per prescribed industry test methods (Figure 1).

[3]

[3]Image courtesy ABAA

To be sure, relevant requirements are a valuable baseline, so an overview frames this discussion. At least 47 states or jurisdictions within states and the District of Columbia adopted the 2012 International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) requirements. Requirements for air barriers tend to evolve slowly. While IECC updates every three years, state and local adoption takes time and is not mandatory. New 2018 IECC requirements were published for the industry’s consideration in August 2017.

The fundamental science of air barriers remains the same, though new studies can improve clarity as the building industry adapts. This means specifying air barriers requires an understanding of both product characteristics and science in order to ensure the selection meets the demands of the project and provides strong value in terms of cost and long-term performance.

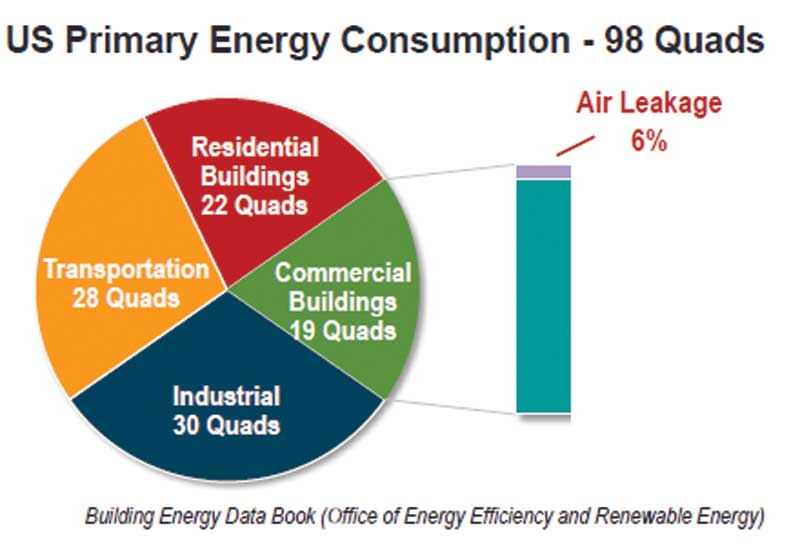

In general, air barrier assemblies can help reduce building energy demands, minimize HVAC sizing requirements, and improve indoor air quality (IAQ) and occupant comfort. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) estimates average air leakage in commercial buildings is six percent, representing substantial energy loss (Figure 2). (Further information on this review can be found in the article, “After London Fire, 600 Tower Blocks Must Be Tested for Flammable Cladding,” published in June at www.reuters.com/article/us-britain-fire-cladding-idUSKBN19D0W5[4].) Leakage rates would likely be even higher in the industrial and transportation sectors due to structures with uninsulated roofs, vehicle entryways, loading docks, multiple vents, and similar problems. Liquid-applied air barriers—including water-based acrylic air barriers low in volatile organic compounds (VOCs)—can usually reduce installation costs and maximize installed value while meeting or exceeding key requirements.

[5]

[5]Images courtesy Kemper System America

Safety first

There are at least three primary criteria for selecting a liquid-applied—or any—air-barrier material or system: air leakage, weather resistance, and vapor permeance. These are in addition to safety standards, which may be even more important in terms of risk management. While a zero-risk world does not exist, decisions about building materials can have long-term consequences. The deadly blaze at a residential high-rise in London this June sparked a review of cladding materials on 600 tower blocks. (Learn more with “Spray Polyurethane Foam Under Fire in CA,” published in Durability+Design in June.) In an uncertain world, building codes provide a level of due diligence.

Many construction materials, from wood to polystyrene, are flammable or can ignite; even steel melts at extreme temperatures. Over the past five to seven years, the industry has shifted away from some traditional barrier options such as asphalt-based materials for above-grade exterior walls, and toward water-based barrier coatings. More residential and commercial codes and architects are also specifying fire test standards such as ASTM E84, Standard Test Method for Surface Burning Characteristics of Building Materials, and National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 285, Standard Fire Test Method for Evaluation of Fire Propagation Characteristics of Exterior Non-loadbearing Wall Assemblies Containing Combustible Components (which measures the spread of fire and smoke in length and width on a test assembly).

Some fluid-applied air barriers dry to a film as thin as 0.6 to 0.75 mm (20 to 25 mils)—the less mass a barrier has, the less there is to support combustion. Other barrier materials that are part of the assembly, including insulation, may produce smoke or toxic fumes. Earlier this year, the California Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC) proposed listing sprayed polyurethane foam (SPF) as a ‘priority product’ due to concerns about exposure to unreacted methylene diphenyl diisocyanate (MDI) during application. (This information is derived from an American Institute of Architects [AIA] presentation, “Proper Use and Application of Air Barrier Systems,” by Jim Arnold, one of this article’s authors.) When foam plastic insulation is used in exterior walls (for Types I, II, III, or IV), the International Building Code (IBC) requires exterior wall materials—including the air barrier assembly—meet NFPA 285.

Air barrier baseline

Beyond safety considerations, the three primary criteria for specifying liquid air barriers are aimed at providing value for owners by reducing building energy requirements and operating costs, including maintenance.

Air leakage

Testing provides an indicator of air permeance (i.e. the rate of air leakage through a material). An air barrier material must achieve air leakage of less than 0.002 L/(s • m2) @ 75 Pa (0.004 cfm/sf @1.57 psf), per ASTM E2178, Standard Test Method for Air Permeance of Building Materials. In the field, a liquid air barrier consists of both the primary air barrier material and components such as primed and self-sealing tapes and adhesives, which comprise the air barrier assembly. Board and sheet materials may also use tapes, adhesives, or foams. However, they require additional labor for sealing board-to-board seams, fasteners, and structural transitions, and these details add to the potential for air infiltration.

Air barrier assemblies are usually tested in accordance with ASTM E2357, Standard Test Method for Determining Air Leakage of Air Barrier Assemblies. The entire assembly is tested in three phases—positive and negative air pressure, then simulated wind gusts up to 159 km/hr (99 mph). As the entire system is under test, the maximum leakage permitted is 10 times higher than for the material alone. The test specifies a maximum air leakage not to exceed 0.02 L(s • m2) (0.04 cfm/sf) under a pressure differential of 75 Pa (1.57 psf). ABAA supports the data from ASTM E2357, which is the most critical information available to the designer when determining air leakage.

Air barrier assemblies can pass ASTM E2357 with any one of three types of test walls or test assemblies:

- opaque wall;

- continuity at penetrations; or

- foundation interface at opaque wall (with modifications).

The second is the most difficult, because it includes any penetrations around vertical and horizontal joists, junction boxes, masonry ties, and a window opening. This makes the second test wall highly important, though not all liquid air barrier assemblies will use it to qualify or can do so in a single coat. (More than 1.8 to 1.95 mm [60 to 65 wet mils] usually indicates more than one coat.)

[6]

[6]Weather resistance

Some air barrier materials also act as water or weather barriers. Under ASTM E331, Standard Test Method for Water Penetration of Exterior Windows, Skylights, Doors, and Walls by Uniform Static Air Pressure Difference, test assemblies should remain watertight. Assembly enclosures are tested with the inside air pressure 299 Pa (6.24 psf) lower than outside and a continuous water flow rate of 29 L/hr/m2 (5 gal/hr/sf). This simulated downpour is equivalent to 2 m (8 ft) of rain per hour.

Weather tests can also simulate wind conditions, as does ASTM E2357. High sustained winds can lift cladding and underlying insulation boards or barrier sheathing—especially those not fully adhered—and expose exterior walls to the full force of a storm. Of course, fluid-applied air barriers are not subject to wind uplift when applied directly to block or other solid-surface walls, and are frequently specified for these particular applications.

Vapor permeance

Water vapor can get trapped inside the cavity of new masonry foundation walls, or moisture from the air can condense inside exterior wall construction layers. New wall assemblies are generally insulated and covered with some combination

of plywood or oriented strand board (OSB), glass-faced sheathing, polyethylene film, or other sheet or sheathing material, plus a separate air barrier. Moisture trapped inside the cavity or interior wall materials can cause mildew or serious mold conditions. Vapor-permeable air barriers allow water vapor to escape through controlled diffusion.

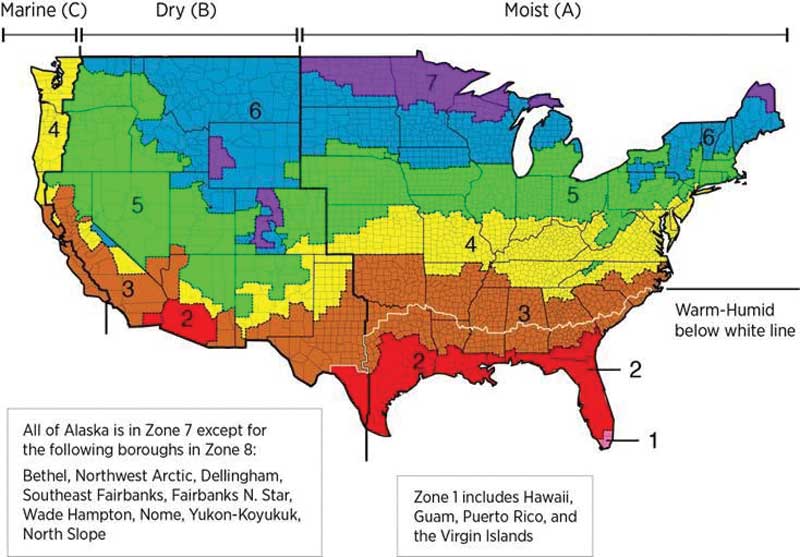

Moisture condensation can pose an issue in both warm and cold climate zones with even moderate humidity because of the wide temperature differential between inside and outside air. Trapped moisture tends to condense on the warmer side of a material. In warm, moist areas of the country, though, the exterior wall assembly is quite different. For example, Climate Zones 1 to 3 do not require any class of vapor retarder on the interior surface of insulation in insulated wall assemblies (Figure 3).

There are three general classes of vapor retarders:

- Class I, rating 0.1 perm or less;

- Class II, rating 1.0 perm or less and greater than 0.1 perm; and

- Class III, rating 10 perms or less and greater than 1.0 perm.

IBC and IECC define vapor retarders as having a water vapor permeance of 1 perm or less when tested in accordance with ASTM E96, Standard Test Methods for Water Vapor Transmission of Materials. (Diane Hun et al’s study, “Air Leakage Rates in Typical Air Barrier Assemblies,” was published by Oak Ridge National Laboratory [ORNL] and the U.S. Department of Energy [DOE] last November.) However, a higher level of vapor permeance is generally desired in an air barrier. ABAA recommends air barriers in the 10- to 20-perm range to permit vapor transmission out of building materials. This is because large amounts of air movement can bring large amounts of moisture (Figure 4).

Water vapor condensation happens when materials used in the envelope are ineffective at controlling air infiltration and exfiltration due to many cracks or high permeance to air. The air entry point and exit point are often distant from each other, giving the moisture-laden air enough time to cool below its dewpoint and condense on colder surfaces within the enclosure assemblies, causing IAQ problems, mold growth, corrosion, rot, and premature failure of the building enclosure.

High relative humidity (RH) affects the overall vapor transmission through a material and in the direction of the drier air. When it is warm outdoors, moisture tends to migrate toward dry conditioned air inside. In cold outdoor temperatures, higher vapor pressure from the warm air inside a building tends to push vapor outward. There are two ASTM E96 test methods performed at standard temperature. Method A (dry) uses a dessicant inside a cup sealed with the material under test, and Method B (wet) uses distilled water in the sealed cup. Both can be useful for understanding how a vapor-permeable membrane performs under different humidity conditions.

Generally, air barriers that can cost-effectively meet ABAA-recommended vapor permeance in the field should be the basic project performance goal. For this reason, some project specifications require a minimum of 1.2 mm (40 mils) to achieve desired crack bridging and other film properties. Thinner barrier films may not achieve continuous coverage, and if a second coating is required, that doubles the cost of materials and labor—and also reduces actual vapor permeance. At the other extreme, liquid air barriers requiring more than about 1.8 mm (60 mils) to achieve rated properties are more likely to slump during application, and are typically applied in two thinner coats to achieve total mil thickness. Medium-mil products (i.e. those ranging 0.9 to 1.5 mm [30 to 50 mils]) can be applied in one pass, saving labor costs.

Figure 4 summarizes baseline specifications for several different types of liquid air barriers. Figure 1 lists these and other test performance standards that are often important in the final selection. Pull tests should be performed on different substrates per ASTM D4541, Standard Test Method for Pull-off Strength of Coatings Using Portable Adhesion Testers, Method E, and those results should be part of the application criteria. It is important to always check with the manufacturer to determine compatibility of products that will be used with the air barrier system.

[7]

[7] [8]

[8]Ratings and reality

Ratings for both the primary air barrier materials and the air barrier assemblies are important for product comparisons. Ratings for the latter, however, offer a perspective one step closer to actual field conditions, since components are tested together as a system.

It should be understood air barrier material and assembly specifications for any given product or system are generated under laboratory conditions, usually by independent test labs. Test assemblies are constructed to be as airtight/watertight as possible before final test results are reported. There can obviously be a significant difference between performance derived under laboratory conditions and the field. For this reason, ABAA recommends verified air barrier products

and assemblies be installed by ABAA-certified installers. Such individuals have gone through a three-day class in each category of air barrier to learn best practices. Some manufacturers also offer training programs, often through distributors, and provide onsite training and technical support for major projects.

Proper installation is essential to achieve desired air barrier properties. Quality assurance inspections done while installation is in progress have generally proven to be the most effective way to manage the final installed performance. Of course, finished structures can also be air-barrier tested, which may be required or desired in some circumstances, particularly for commercial construction. However, field testing adds a cost and may not always be practical. If there is an issue with an air barrier once the exterior wall has been cladded, additional certified tests may be needed, and expenses can mount. Rework can be very expensive.

Specifying ABAA-verified ASTM E2357 assemblies is generally the shortest route to air barrier compliance, though it is always important to check state and local code requirements. ABAA verification indicates the assembly meets not only the basic requirements, but also the additional test requirements in Figure 1. However, specifiers should always be mindful actual field performance is the ultimate goal of construction projects, and the industry as whole.

DOE, which also supports IECC and American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) standards fostering energy conservation, is also interested in the distinction between test and field performance and ways to close the gap. A study conducted by Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) for DOE last year examined air leakage rates in typical air barrier assemblies for residential buildings. The study reviewed how airtightness of residential walls heavily depends on the skills of installers. Although liquid air barriers were not the focus of the study, the results are informative for both residential and commercial construction.

Specifically, the study examined both insulating and non-insulating sheathing, as well as mechanically fastened membranes or housewraps, widely used as water barriers (though not necessarily air barriers) on new homes in the United States. Nine test walls (three of each type) were erected by three different installers. Air leakage was then measured based on procedures set by ASTM E283, Standard Test Method for Determining Rate of Air Leakage Through Exterior Windows, Curtain Walls, and Doors Under Specified Pressure Differences Across the Specimen, with leakage rates normalized to standard temperature and pressure. The results indicated wide variability due to workmanship, with flow rates varying up to 200 percent from their average values. Most of the average leakage rates exceeded the IECC maximum leakage rate. The researchers noted variability will likely be higher under actual field conditions.

The study also quantifies the potential impact of imperfections in air barrier assemblies at foundation wall joints, at wall-roof joints, and around electrical outlets. Such airflows are not always easily tackled by air barriers, and not always addressed in installation manuals. The study calculated if left unsealed, these three areas alone could contribute 27 percent to total air infiltration (per IECC leakage requirements for homes in Climate Zones 3 and above).

[9]

[9]Liquid-applied air barriers

When one considers exterior walls are not always vertical and never completely flat, the general advantages of liquid-applied air barriers become clear. Building façades may be angled or curved. Wall expanses may be interrupted by windows and doors, balconies and overhangs, columns, or outcroppings. There may be multiple penetrations for electrical or plumbing connections. Inside and outside corners of walls and edges are also obvious areas of air infiltration.

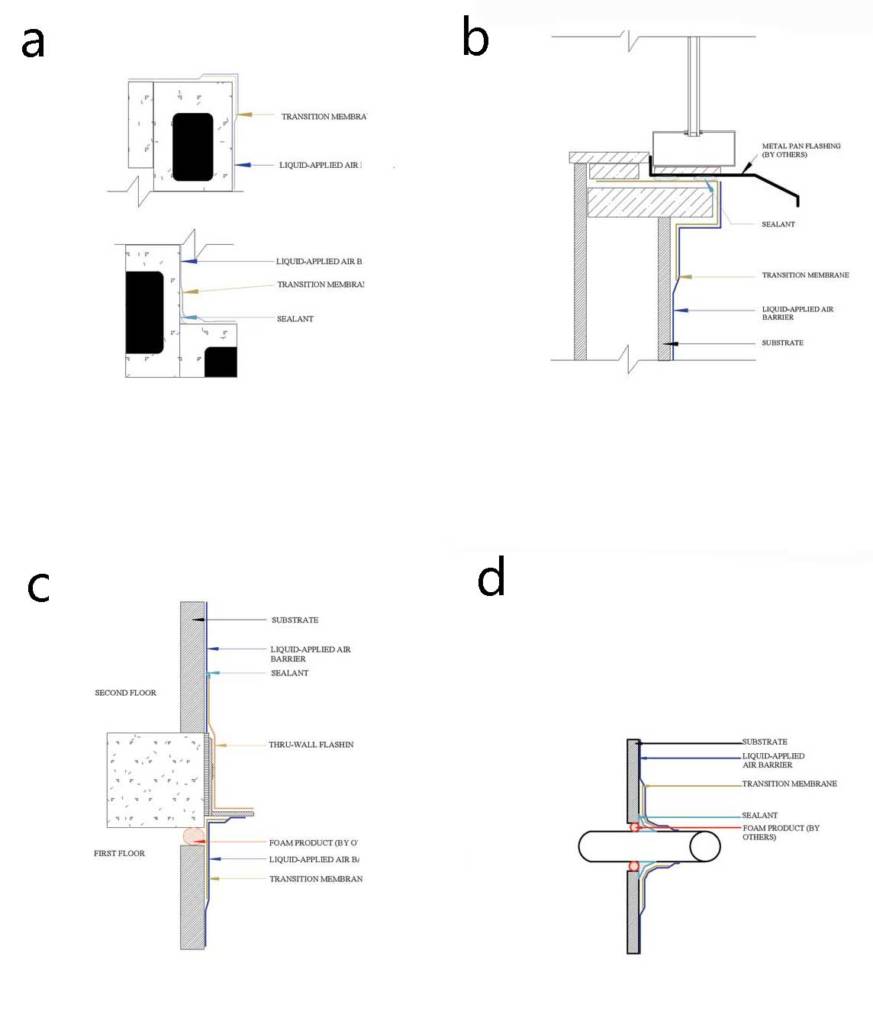

The success of any air barrier depends on the ability to handle application details. Liquid-applied air/weather barriers provide seamless protection across exterior wall surfaces and offer versatility for sealing difficult areas. Figure 5 shows recommended details for a variety of applications with liquid air barriers, sealant, and transition tape. All air barrier manufacturers define how to address these details using air barrier components customized to the type of product being applied.

Component materials used in any air barrier system must be compatible with one another and substrates that include flashing materials. When necessary, primers may be employed to key adhesion, such as over weather-coated OSB and exterior drywall.

Once detailing with sealants and tape is complete, liquid air barriers can be applied to field areas with heavy-duty sprayers, rollers, and brushes for spot coverage. Sprayers are generally the fastest method for expansive exterior wall surfaces, including concrete masonry units (CMUs). Rollers are almost as fast and can be faster on foundation walls and low-rise buildings where no scaffolding is required. This method is preferred under windy conditions and at elevations where overspray may be an issue. High-nap rollers are useful for coating porous or uneven surfaces such as brick or block. Proper coverage for a liquid barrier coating is readily identified by continuous coverage and opacity. Coverage in field areas can be checked as the coating is applied using a simple wet mil gauge. If needed, additional coating can be applied while the film is still wet.

Most liquid-applied products can be exposed to the elements for at least 90 to 180 days, which can be essential for construction scheduling. Like other exterior coatings, they should not be applied with rain in the immediate forecast, or under very cold conditions. Liquid-applied barrier coatings can dry quickly, though curing takes longer, and time varies by product and ambient conditions. In warm climate zones, most products can be applied year-round. In more temperate zones, some products are best applied during the normal May to October construction season. Silicone-based products can generally be installed at lower temperatures and to damper surfaces, and can withstand moisture sooner than acrylics. However, some silicones may be vapor-impermeable.

Before specifying any air barrier, specifiers should consider the ability to achieve performance requirements at low installed cost. For many construction projects, liquid air barriers can substantially reduce installation costs compared to other systems—especially self-adhered sheet membranes. These usually take a larger crew and require a primer to be applied to the entire surface first. More labor steps mean a higher cost. Field performance is crucial, so ease of application

and the ability to quality check in the field are important advantages. All materials have their intricacies—for instance, sheet goods can create minute ‘fish mouths’ and air pockets that may go unnoticed. In contrast, liquid-applied air barriers leave a monolithic surface so the installer can easily scan and correct imperfections.

While liquid air barriers are not all the same, as a class they are extremely versatile and can often be applied in a single coat. Meeting or exceeding industry specifications should be a priority, but beyond this, single-pass coverage is perhaps the most important selection criteria for achieving the best value.

James Arnold, PE, RRO, is director of product development for Kemper System America, Inc. He brings more than 30 years of experience from the design, construction management, and roofing industries to his role. Arnold can be reached via e-mail at jarnold@kempersystem.com[10].

Lynn Walters is West Coast regional sales manager for Kemper System. He is a committee member with the Air Barrier Association of America (ABAA), serves on the board of directors of the Reflective Insulation Manufacturers Association (RIMA), and is a member of ASTM International, the Cool Roof Rating Council, and RCI. Walters has 30 years of experience with energy-efficient building envelope systems. He can be reached via e-mail by contacting lwalters@kempersystem.com[11].

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/AustinCC_Menjivar_08-17.jpg

- New Air- and Water-resistive Technologies for Commercial Buildings: http://energy.gov/eere/buildings/downloads/new-air-and-water-resistive-technologies-commercial-buildings

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/fig1.jpg

- www.reuters.com/article/us-britain-fire-cladding-idUSKBN19D0W5: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-britain-fire-cladding-idUSKBN19D0W5

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Figure-1.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/U.S.-Map-Where-Commercial-Air-Barriers-are-Required.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/figure-4.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Wall-Guardian-air-barrier-spray-application.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/figure-5.jpg

- jarnold@kempersystem.com: mailto:jarnold@kempersystem.com

- lwalters@kempersystem.com: mailto:lwalters@kempersystem.com

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/building-envelope-workhorses-growing-role-fluid-applied-air-barriers/