Image courtesy W.R. Meadows

Keeping things dry

With no room to excavate, waterproofing is complicated and tricky. At the same time, many building types are taking greater advantage of below-grade spaces to maximize site usage and save costs. Healthcare facilities, for example, are using this space for imaging equipment; the result helps control vibration while providing better shielding. Hospitality spaces prefer to reserve anything above ground for profit-making facilities, while below-grade space holds back-of-house functions, workout space, and conference rooms. Below-grade is also perfect for ‘wine cellar’ restaurants and pubs.

Another reason more buildings are going deeper is it helps them meet American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) 90.1, Energy Standard for Buildings Except Low-rise Residential Buildings—an alternative to the International Code Council’s (ICC’s) International Energy Conservation Code (IECC). The 2015 version of IECC requires a 30 to 40 percent window-to-wall ratio. ASHRAE 90.1 allows buildings to include below-grade space in the window to wall calculations. This means deeper below-grade walls allow more glass above grade.

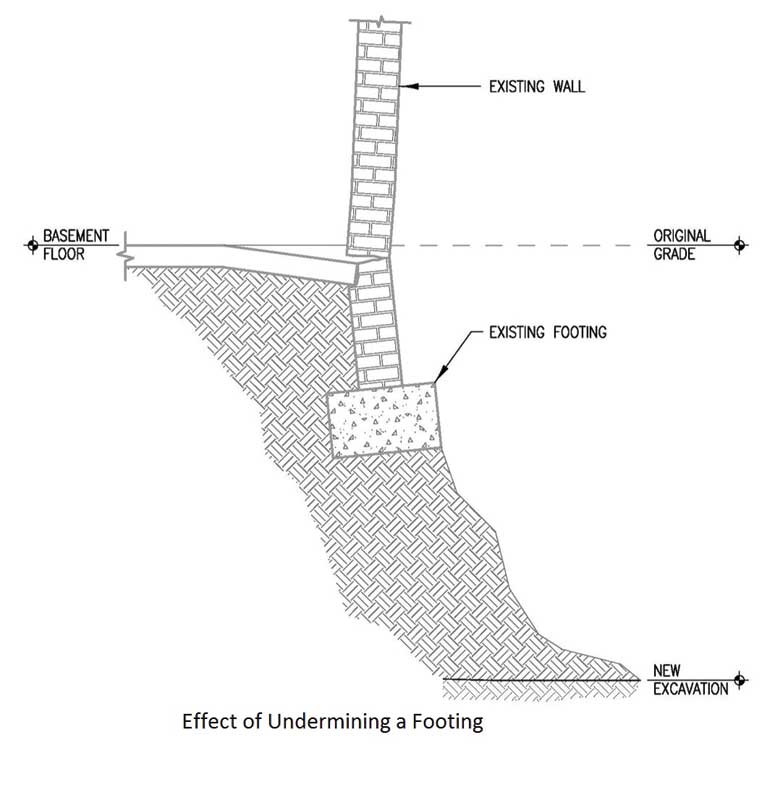

Regardless of the reason, simply excavating the site and taking the soil away can mean complicated site access (e.g. steep ramps) and fussy waterproofing details. In some cases, it is necessary to use blindside or pre-applied waterproofing (see “Marina Heights,” below). This is a waterproofing membrane installed against the lagging, existing walls, or even rock or rubble, and then concrete is poured against it. There may also be a mix of waterproofing techniques—negative waterproofing on existing walls and blindside on new walls, for example.

If multiple membrane types are used, the ability to tie the systems together to ensure a continuous watertight seal is critical. Membrane systems must not only be able to tie together with proper detailing, but they must also be manufactured from compatible materials. Whenever possible, dealing with a single manufacturer to ensure compatibility and continuity is beneficial.

Happy together

Once the base of the building is solid and the walls go up, new problems arrive in the name of cranes. How and where these are placed is a mathematical equation on tight sites.

Laydown is another complication. Often sidewalks are cramped and the only place to put anything is right on the site. On some projects, there is barely room for an office, let alone a trailer.

The solution to all these problems is teamwork, and this means early and frequent meetings. It also means keeping everyone informed at every step of the way. This is easy to say and quite another thing to accomplish, especially when the budget is tight (as it always is) and time is short (another constant truism).

Integrated project management involves making trade-offs among competing objectives and alternatives to meet or exceed stakeholder needs and expectations. In the end, it is about compromise.

| MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION |

| In April 2017, the Museum of the American Revolution, designed by Robert A.M. Stern, opened in the Old City section of Philadelphia. Located on the southeast corner of Third and Chestnut streets, the site is hemmed in by an active security driveway on the east and a utility building on the south.

The site is in a very active historic and entertainment district, which means there is a lot of pedestrian traffic on the streets and alleys around the building, as well as food deliveries at all hours. Public safety and traffic flow were important planning considerations. To maximize the interior volume, the basement walls were located as close as was practical to the property lines on all four sides. The building façade on the east and south sides cantilevers over the foundations to the lot lines, while the north and west sides are set back to allow generous sidewalks and a plaza. Since the height of the building was constrained by zoning, the basement is not utility space but rather dedicated to conservation of important artifacts from the colonial era. While the basement slab is just above the design water table, the basement was nonetheless designed to be waterproof because of the critical importance of its contents. This meant the waterproofing had to be applied to the blind side of the foundation walls and basement floor slab, and made continuous by appropriate attention to the transition details. An intercepted underground spring discovered during excavation gave added weight to the importance of this work. Early on, the team realized there was no place to park a standard mobile crane, which would be the normal tool for a three-story structure. Instead, a short tower crane was used to keep the site access ramp clear. Naturally, the ideal location was to place the tower at the center of the site, but this would require a significant redesign of a main building truss and other important design elements. Through a collegial brainstorming session, it was agreed to shift the location slightly off center to allow the truss to slip by. The large foundation for the crane was incorporated into the column footings. Since the crane would now not reach one far corner of the site with its necessary load capacity, two of the precast panels were installed using a temporary mobile crane, located for a short time on a neighboring driveway. Outside-the-box thinking and the willingness of the owner and design team to be flexible on these sorts of details greatly improved the construction process. |

Wendy Talarico, LEED AP, is the architectural services specialist for W.R. Meadows. She is an instructor for Urban Green/New York State Energy Research and Development Authority’s ‘Conquering the Code’—an eight-hour energy class for architects and engineers. Talarico has also worked as a member of the engineering outreach team for the Brick Industry Association (BIA) and has more than 25 years of experience writing and editing. She is a member of CSI as well as the American Institute of Architects (AIA) DC High-performance Buildings committee. She can be reached via e-mail at wtalarico@wrmeadows.com.

Frederick C. Baumert, PE, CCS, is a structural engineer and principal at Keast & Hood Structural Engineers (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania). A member of CSI, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), Association for Preservation Technology International (APT), and the Carpenters’ Company of the City and County of Philadelphia, he has 37 years of experience designing new buildings and renovating old and historic structures throughout the mid-Atlantic region. Baumert can be reached at fbaumert@keasthood.com.

Excellent points. Great case studies