Building on Solar Reflectance: Meeting cool roof standards with concrete and clay tile

by Katie Daniel | March 7, 2017 10:26 am

[1]

[1]by Rich Thomas, LEED AP, and Steven H. Miller, CDT

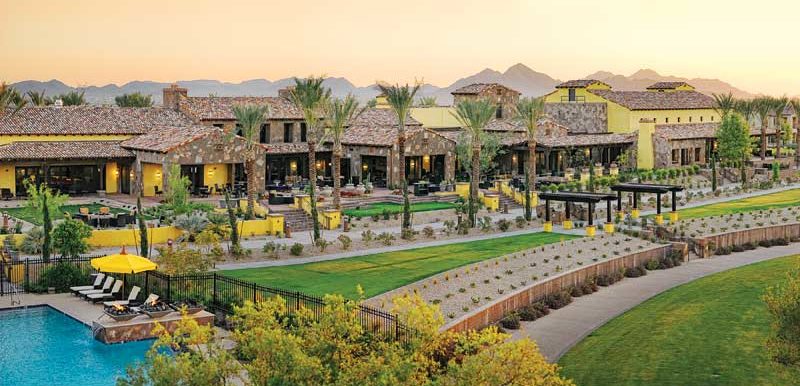

To many design professionals, the term ‘cool roof’ means a flat roof with a white membrane—a high-reflectance roof that performs well, but needs to be hidden from view. This is a very unfortunate misconception. There are other roofing options that can also contribute to a building’s architectural statement while meeting cool roof standards. Tile roofs—both concrete and clay—are cool by design in ways that include solar reflectance, as well as going beyond it.

Pitched tile roofs not only present a designable surface to the world, but also have inherent material and structural properties that combine to make the assembly highly effective at dealing with solar energy: high thermal emissivity, high thermal mass, natural insulation, and passive ventilation. An air channel beneath the tile—formed by the tile’s structure—not only reduces heat transference during summer days, but also mitigates heat loss during the colder seasons.

Tile cool roofs allow architects to design roofs that help combat ‘urban heat island’ formation and make the building cooler, more energy-efficient, and less costly to operate without sacrificing architectural style.

What is a cool roof?

Every day, energy from the sun, in the form of electromagnetic radiation, bombards the Earth. The visible wavelengths reaching us are sunlight, but about half the radiation is infrared (IR) wavelengths longer than those in the visible spectrum. When infrared impacts water or solid objects that absorb it, it is transformed into heat. This heat is the source of all fuels on the planet (i.e. our major source of stored energy) and the climate conditions allowing Earth to be inhabitable—it grows all vegetation, is responsible for the heating and cooling cycles driving the weather, produces wind energy, and delivers rainwater.

On a clear day in the temperate zone, sunshine falls with an intensity of about 10,765 watts/m2 (1000 watts/sf). If a roof absorbs and holds most of that energy, it gets very hot; if it reflects a significant percentage, it will be cooler. Equally important, if the roof can disperse the heat it absorbs, or in other ways prevent it from being transferred to the building below, the building will be cooler in hot weather. The temperature immediately below a cool roof could easily be 25 C (45 F) lower than below a conventional roof.

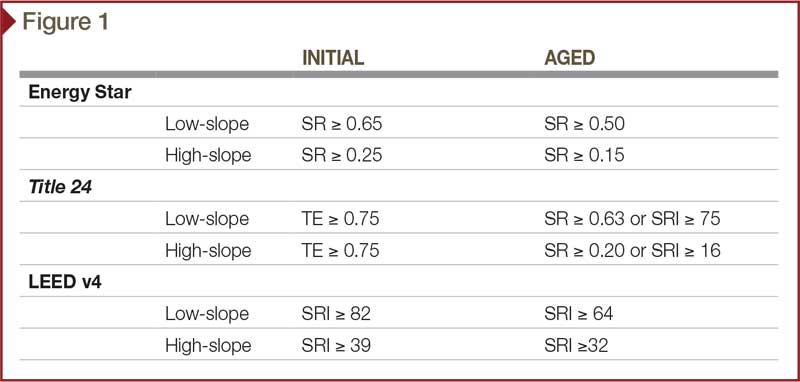

The exact qualifications of a ‘cool roof’ depend on whose definition is being used. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) Energy Star program rating is based on solar reflectance (SR), either “initial” (new product) or “three-year aged.” The U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program uses both reflectance and emittance, as expressed in the Solar Reflectance Index (SRI). The most recent version of LEED (LEED v4) allows either initial or aged SRI to be used. California’s Title 24 uses initial Thermal Emittance (TE) and aged solar reflectance (SR), or aged SRI.

[2]

[2]As shown in Figure 1, all three systems differentiate between low-slope (i.e. a pitch of < 2:12) and high-slope (i.e. > 2:12) roofs. Energy Star and Title 24 have similar SR/SRI thresholds. LEED v4 has much higher requirements to contribute to LEED credits.

In addition to reflectance, both concrete and clay tile have cooling properties stemming from material composition and tile system design. Rating systems do not account for these effects, but there is significant impact upon the roof’s ability to prevent or otherwise mitigate the heat transference.

Why are cool roofs important?

A roof’s heat can have an impact on both the building and the surrounding area. In the summer, even with a normally insulated roof system, heat transmitted through the roof increases the demand for air-conditioning, raising electrical energy consumption. That energy consumption increases air pollution and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions associated with climate change. It also costs more, making the building more expensive to occupy. A cool roof limits heat transference to the interior, reducing all these impacts.

A hot roof also raises the temperature of the air above it. Like any hot object, it gives off heat to things coming into contact with it (i.e. conduction). Heated air rises and causes wind currents that spread the heat around (i.e. convection). A city full of hot roofs becomes a large concentration of hot air, with studies showing it remains hotter, both day and night, than rural areas nearby. Buildings within these urban heat islands may see increased summer demand for air-conditioning (even after dark when temperatures would otherwise cool down), which multiplies the damaging environmental effect. A reflective roof mitigates these impacts on the building and the surrounding area.

A cool roof’s contribution to lowering energy consumption was assessed by Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), in collaboration with Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), in a two-year residential study. (For more, see William A. Miller and Hashem Akbari’s 2005 ORNL report, “Steep-slope Assembly Testing of Clay and Concrete Tile With and Without Cool Pigmented Colors.” Visit info.ornl.gov/sites/publications/files/Pub6113.pdf[3].) Published in 2005, the research found a tile cool roof “reduced the peak heat transfer penetrating the roof deck at solar noon by about 70 percent” as compared to a typical residential asphalt shingle roof. A similar effect could reasonably be expected on one- or two-story commercial buildings, although the exact reduction could vary considerably depending on the configuration of the roof and above-ceiling plenum.

[4]

[4]Cool roof mechanics

A tile cool roof is a multi-layered system. The topmost surface is the one garnering the most attention, but other elements of a tile roof make significant contributions to reducing heat transference to the building below.

From the top down, the layers are:

- tile;

- air channel;

- underlayment;

- roof deck;

- radiant barrier (sometimes included, often as a foil layer laminated to the bottom of oriented strand board [OSB] decking); and

- insulation.

The material properties of clay and concrete tile themselves act in several ways that help keep the roof cooler.

Reflectivity

‘Reflectivity’ is a surface’s ability to make incoming radiation bounce off, still in the form of radiation, rather than be absorbed by the surface and transformed into heat. As is taught in elementary schools, lighter colors reflect more light and stay cooler in the sun because they also reflect infrared. However, there are some materials with fairly dark colors—generally in the orange and red range—that also reflect a significant proportion of infrared. Several shades of clay tile naturally have this property. Most clay tiles achieve their color from chemical changes in the clay caused by the firing process. The color is integral, and very stable, even after decades.

There are also special pigments that are formulated for high IR reflectance, regardless of the lightness or darkness of visible light reflectance. However, they tend to be expensive. (Recent research, for example, showed promising results from a fluorescent pigment made with synthetic ruby.) Some clay tile is made using high-IR-reflective materials that are coated onto the clay before firing, thus resulting in higher IR reflectance.

Concrete color is achieved by mixing integral pigments into the concrete during casting. Concrete tile cool roof colors tend to be lighter shades, although concrete tile made with high-IR-reflective pigments are also possible.

[5]

[5]Emissivity

‘Emissivity’ refers to a surface’s ability to shed radiant energy (as distinct from conducting away heat). Concrete and clay tile both have high emissivity, so a portion of the radiation not instantly reflected is still sent back upward, more slowly, in the form of radiation.

SRI ratings take into account both reflectance and emittance. There are clay and concrete tile colors available with SRIs in the 40s and 50s, which satisfy LEED v4 high-slope cool roof requirements. There are many more colors with SRIs in the 20s and 30s, meeting Energy Star high-slope standards.

LEED is becoming a requirement for public- and private-sector buildings in an increasing number of jurisdictions, and net-zero houses will be mandated in some areas (such as California) in the near future. It is likely manufacturers will make more high-SRI colors available. Lighter-colored roofs are already showing more popularity than in previous eras.

| UNDERSTANDING THE SOLAR REFLECTANCE INDEX |

| The Solar Reflectance Index (SRI) has become the chief quantitative measure used to define cool roof materials. The ability of a roofing material to reflect incoming radiation (i.e. reflectivity) and shed heat back to the exterior (i.e. emissivity) is measured using standard procedures, and expressed as a single, combined rating. The U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) defines this SRI as:

a measure of the constructed surface’s ability to stay cool in the sun by reflecting solar radiation and emitting thermal radiation. It is defined such that a standard black surface (initial solar reflectance 0.05, initial thermal emittance 0.90) has an initial SRI of 0, and a standard white surface (initial solar reflectance 0.80, initial thermal emittance 0.90) has an initial SRI of 100. To calculate the SRI for a given material, obtain its solar reflectance and thermal emittance via the Cool Roof Rating Council Standard (CRRC-1). SRI is calculated according to ASTM E1980. Calculation of the aged SRI is based on the aged tested values of solar reflectance and thermal emittance. Ratings systems take into account the possibility the reflectance of a material may change as it ages, due to color darkening or lightening. Therefore, both an initial SRI and a three-year aged SRI are standard measurements. |

[6]

[6]Beyond SRI

Tile cool roof performance goes beyond reflectance and emittance. It is important to understand that, even with the highest-reflectance materials, some IR energy is not reflected or re-emitted from the surface as radiation. That energy either:

- transfers as heat to the air above it;

- penetrates beyond the surface and builds up in the mass of the tile;

- emits as radiation downward to the building; or

- transfers as heat through the tile to the layer below.

All four of these things happen to different degrees. Tile roofs limit the heat transferring into the building through several mechanisms.

Thermal mass is what allows a material to store energy in the form of heat. Both concrete and clay tile have high thermal mass, so they store heat like a sponge that can soak up a certain amount of water before any starts to drip out. This buildup delays the shedding of heat through the bottom of the tile and toward the building. During daylight, roof tile heats up slowly, and does not begin to transfer heat toward the building until well into the day. After the sun goes down, the heat continues to transfer out of the roof tile, but cooler nighttime ambient temperatures compensate for this. This delay factor reduces both cooling and heating demands.

Insulation is a material’s ability to prevent or reduce heat transfer. Clay and concrete roof tile systems use one of the world’s best insulators as the layer directly below the tile—air. As both clay and concrete tile are hard, structurally robust objects, they can be molded so the body of the tile stands off from the underlayment and roof deck below.

Structural contact (and therefore thermal bridging) is limited to a few points on the underside of the tile. This forms an air channel under the tile assembly with two important effects:

1. It acts as an insulating layer, limiting heat conduction.

2. It creates passive ventilation, using convection to carry heat away. As air under the tile is heated, it rises up the roof’s pitch through the channel and escapes at the ridge, carrying heat with it. This ventilating effect has been shown to play a significant role in reducing heat transference through the roof system.

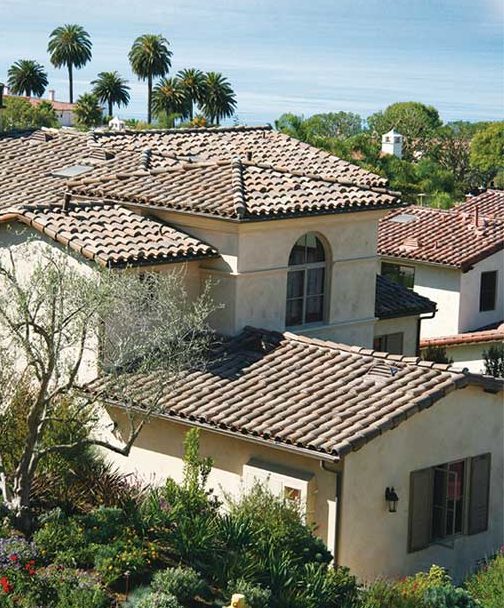

Arched tiles, such as classic clay barrel tile and S-mission tile, have sizeable air channels under their arches. This insulating/ventilating layer has been cooling roofs for millennia, since the time when tiles were molded on the tile-maker’s thigh.

[7]

[7]Flat tiles, including those shaped to emulate traditional materials such as slates or wood shakes, can also be provided with air channels. Tile is normally fastened to battens, nailing strips attached to the roof deck parallel to the roof ridgeline. The tile’s upper edge is nailed to the batten to create a downward pitch from tile to tile, so each tile sheds water to the tile below it. A variant on this method involves counter-battens fastened to the deck running perpendicular to the ridge, and then parallel battens atop those. This creates an air channel under the battens. The ORNL study found slate-shaped concrete tile fastened in this manner caused substantial cooling.

With flat tile, the same effect can be achieved at lower installation expense using specialized, raised battens, which eliminates the need for counter-battens. Air channels are cut through the raised batten’s underside, creating the cooling effect.

The ORNL/LBNL study confirmed the combination of thermal mass and sub-tile air channel substantially reduced heat transfer. It compared a roof with dark concrete slate-shaped tile to a roof with asphalt shingle that had similar solar reflectance and thermal emittance. Temperature was measured both at the roof deck and in the conditioned space beneath the ceiling. The study found at peak solar loading, “deck venting caused a significant 50 percent reduction in the heat penetrating the conditioned space compared to the direct-nailed asphalt shingle roof that is in direct contact with the roof deck.” The data suggested tile with air-channel venting reduced heat transfer equivalent to having a 24-point higher solar reflectance.

Highly reflective roofs, because they limit heating from the sun, cause a penalty during winter—the heating season—when the sun’s warmth would be a welcome addition. However, the ORNL study also found tile roofs mitigated this penalty. A tile roof improves interior heat retention because of the air channel’s insulating effect, while the thermal mass effect adds heat during the night.

Additionally, the roof’s underside may be provided with a radiant barrier, and thermal insulation may be installed below the roof and above the conditioned space, both of which improve thermal performance even further. A radiant barrier—usually an aluminum foil layer—stops penetration of the IR that is being emitted downward by the tile. Insulation prevents heat transfer by convection and conduction into the conditioned space.

Design options

The tile cool roof system’s thermal performance allows design professionals to achieve sustainability goals and still have a broad range of aesthetic options. There is no need to compromise architectural vision to hit a cool roof target. Unlike a white membrane roof, which is usually hidden from street view by a parapet screening off its unappealing aesthetics, a tile cool roof can make an architectural contribution. It can create a connection to traditional architecture, or express entirely contemporary, breakaway ideas.

[8]

[8]Pitched roofs on low-rise commercial buildings often convey a ‘home-like’ quality with a safe and welcoming sensibility—an effective strategy for any hotel, restaurant, public library, or other building seeking to encourage public access. Steeply pitched mansard roofs on high-rise buildings reference late 19th-century grandeur.

Cool roof tiles are available in both traditional and contemporary styles. Barrel tile is the classic clay style, dating back thousands of years. Concrete versions in this style are also widely available. Both clay and concrete can be molded to resemble other traditional materials, such as slate tiles, wood shingles, and wood shakes.

Cool roof tiles can also support contemporary designs. Some generally resemble traditional shapes such as slates, but do not try to emulate traditional colors or textures. Instead, they may feature smooth textures, and colors not associated with wood, clay, or stone.

Many linear and geometric effects can be created by staggering the tile placement. Combined with the possibilities of using multiple colors—distributed randomly or arranged in patterns—a tile roof can truly become a canvas for architectural expression.

[9]

[9]Beyond cool

Beyond their cool roof aspects, both concrete and clay tiles have other sustainable qualities.

Regional materials

Clay and concrete tile are manufactured in many parts of the country. Raw clay is locally sourced throughout the United States as a waste product of other mineral extraction operations. It is not only used for clay tile, but also as one of the two main raw materials of Portland cement powder, which is used to make concrete. Since most clay and concrete tile products are sold in the region where they are manufactured (to reduce costs associated with shipping), they often qualify as regional materials. However, not all colors and styles are equally available in all regions.

Both cement manufacturing and clay-tile firing are high-heat processes, with the associated CO2 emissions. However, modern manufacturing technologies have significantly lowered the energy consumption and increased the efficiency of these processes; in the best plants, they are more sustainable than they have ever been.

Long life cycle

Both materials have very high durability and long service life, reducing material consumption inherent in replacing them. Neither suffers noticeable degradation in performance over time unless they are physically damaged, and it takes considerable abuse to do so.

Concrete tiles are generally expected to last at least 50 years. Integrally pigmented concrete may exhibit slight color loss, especially during the first few years, as some less-adhered pigment particles in the surface layer get washed out by rain or snow. This slight lightening of color can result in a slightly higher three-year aged SRI than the initial SRI, possibly resulting in improved cool-roof performance.

Clay tile often lasts for centuries. The material generally does not exhibit much change in color or other performance factors during its service life. Also, like concrete, clay is recyclable at the end of its service life.

[10]

[10]Photo © Steven H. Miller

Design considerations

Roof pitch is both an aesthetic and performance choice. Steeper pitches shed water and snow more readily, and may stay cleaner because rain tends to wash them easily. In regions with intense rainfall or high snow loads, lower slopes may not be suitable.

The ORNL study found some lighter-colored tile experienced a slight reduction in reflectance due to soiling by air pollution and airborne dust over the course of two years of exposure. This effect was more pronounced at test sites in a highly populated urban area of California and in the desert than it was in a more rural (and more moist) region of Tennessee. A steeper-pitched roof was also observed to show less loss of reflectance than a lower-slope (2:12) roof. The hypothesis is wind action kept the tile cleaner. For pitched roofs in urban areas, or regions such as the Western United States where dry and dusty conditions prevail, slopes of 4:12 and greater may be advisable to limit reflectance loss.

A cool roof’s efficiency varies with the climate. Locations experiencing a large differential between daytime and nighttime temperatures benefit more from the thermal mass effect. Regions with a high proportion of rainy or overcast days will not enjoy as large a reduction of cooling costs or energy consumption, because they have lower need for cooling.

Conclusion

Concrete and clay tile cool roof systems are highly effective at reducing heat buildup both inside and around buildings. Their effect extends beyond the building walls to include minimizing contributions to urban heat islands. As code requirements gradually increase the proportion of cool roofs in urban areas, heat islands become less intense, and their multiplier effect on energy consumption and carbon emissions decrease.

In many ways, the various styles and colors of cool roof tile assemblies take the handcuffs off design professionals, allowing them to create architectural roofs compatible with high sustainability goals. As those goals continue to evolve with more stringent standards, clay and concrete tile manufacturers can be expected to respond with even more efficient and effective products.

| LEED POSSIBILITIES |

A cool roof may contribute to credits in the U.S. Green Building Council’s (USGBC’s) Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Building Design and Construction v4 (as well as credits in LEED for Schools, LEED for Neighborhoods, and LEED for Homes). For LEED v4, possibilities include:

|

Rich Thomas, LEED AP, is product manager for Boral Roofing, a manufacturer of clay and concrete roof tile. He has been involved in the roofing industry for 28 years, focusing on energy-efficient roof systems as a key aspect of roofing design. Thomas can be reached at rich.thomas@boral.com[11].

Steven H. Miller, CDT is a freelance writer and photographer, and a marketing communications consultant specializing in the construction industry. He can be reached via e-mail at steve@metaphorce.com[12].

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/concrete_Cielo-CustomBlend-Panorama.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/claytile_fig1.jpg

- info.ornl.gov/sites/publications/files/Pub6113.pdf: http://info.ornl.gov/sites/publications/files/Pub6113.pdf

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/concrete_1-pc-S-Tile-CustomBlend.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/concrete_CoolRoofSystem-w-TileSeal.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/concrete_dark.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/concrete_Batten.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/concrete_Clay-Serpentine.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/concrete_PNW-Slate-MissionRed-MooseHotel-026-300.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/concrete_IMG_7399Vienna-CR2-Stefanskirche-corr-2.jpg

- rich.thomas@boral.com: mailto:rich.thomas@boral.com

- steve@metaphorce.com: mailto:steve@metaphorce.com

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/building-on-solar-reflectance-meeting-cool-roof-standards-with-concrete-and-clay-tile/