By Zachary Lovett, David Diedrick, and David Figurski

Despite the urgency and efforts to halt global warming, the world’s output of CO2 continues to rise according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).1 Average global temperatures are now approaching 1.5 C (34.7 F) above preindustrial levels, and 2023 was the hottest year on record.2

Buildings are responsible for approximately 42 percent of CO2 emissions, 15 percent of which is attributed to the embodied carbon of materials.3 With the world expected to add about 241 billion m2 (2.6 trillion sf) of building floorspace by 2060—equivalent space of New York City added every month for 40 years—the time for the industry to act is now.4 This means embracing building products with the lowest embodied carbon possible without compromising performance. At the same time, the built environment must adapt to the impacts of an already-changing climate by optimizing the resiliency of structural systems.

Designing for resilience

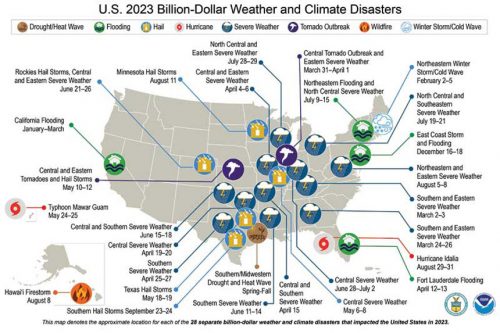

As climate-related stressors intensify, resiliency—the ability to adapt to, withstand, and rapidly recover from hazards—has become an increasingly urgent issue for building owners, government officials, property insurers, and design and construction professionals.

Model building codes (I-codes) developed by the International Code Council (ICC) play a crucial role in constructing safe, sustainable, and resilient structures. Moreover, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) provides guidance on designing buildings to mitigate the impact of severe weather. These FEMA guidelines, which support the I-codes and American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) standards, incorporate findings of the National Earthquake Hazards Reduction Program (NEHRP) and reflect the current state-of-the-art engineering requirements for wind design.

Millions of properties across the U.S. are vulnerable to flooding, hurricanes, tornados, and wildfires, motivating insurers to take steps to educate policyholders on fortifying their buildings to help make disasters less damaging and costly. One such initiative is the Fortified for Safer Living program of the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS). This nationally recognized “code-plus” program goes beyond typical building codes to significantly increase a building’s disaster-resilient design and construction.5

Stronger and safer buildings

Concrete is the world’s most widely used construction material due to its significant performance, sustainability, and cost advantages. Most of its components are naturally occurring. Concrete can also be produced from recycled products, plus it is recyclable and has a long lifespan. These attributes come in addition to the material’s unequalled durability, high thermal mass to improve energy efficiency, and other characteristics allowing for its successful adaptation to the realities of climate change.

High-performance concrete buildings are especially well-suited to provide structural resistance to extremely high winds and flying debris associated with hurricanes, tropical storms, and tornadoes. They are also resistant to wind-driven rain, hail, flood damage, decay, and mold, which can result in structural damage and pose health and safety risks. Concrete buildings are also the safest and most structurally sound types of structures during an earthquake, and their slow rate of heat transfer and inherent fire resistance enable them to tolerate flames and slow their spread.

While concrete plays an important role in creating stronger and safer buildings, this essential construction material has a large carbon footprint due to ordinary Portland cement (OPC). Given this is responsible for 90 to 95 percent of concrete’s carbon intensity, reducing the amount of OPC in mixes is critical to decarbonizing the built environment and stabilizing global warming.

Decarbonize without compromise

There is a wide variety of innovative solutions available and under investigation at some companies to significantly reduce the embodied carbon of concrete without compromising on performance. Embodied carbon refers to the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions generated by the manufacturing, transportation, installation, maintenance, and disposal of construction materials used in the built environment. The metric used to define embodied carbon and the potential climate-change impact of a product is global warming potential (GWP), which is calculated using a standardized methodology called life cycle assessment (LCA).

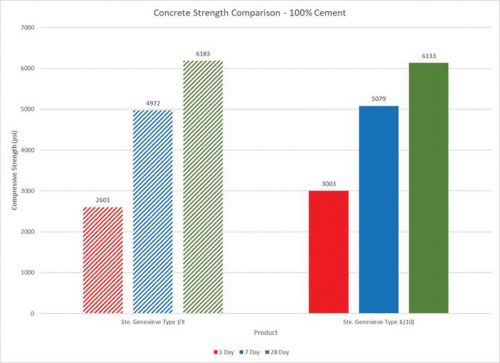

One solution for reducing the embodied carbon of concrete is to seamlessly replace Type I/II OPC in mix designs with Type IL Portland Limestone Cement (PLC), which is engineered with a higher limestone content. Widely adopted by industry standards and building codes, Type IL cement allows for direct reduction in carbon across all classes of concrete. As an example, a manufacturer’s PLC product offering reduces CO2 emissions by five to 10 percent per tonne (ton) of cement. Based on extensive laboratory and field performance testing, PLC also provides equivalent performance to OPC. Figure 1 shows the compressive strength comparison of Type IL and Type I/II cements.

In addition to Type IL PLC, other blended cements and supplementary cementing materials (SCMs) can be used to replace OPC and reduce the GWP of concrete while enhancing performance. The most commonly used SCMs—fly ash, slag cement, and silica fume—provide economy, improved workability, long-term strength and durability, and increased sustainability. The beneficial reuse of these materials in concrete contributes to world-class environmental certifications, such as LEED, Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM), Green Globes, and Living Building Challenge.

Regional challenges exist with sourcing a reliable supply of fly ash due to the ongoing retirement of coal-fired power plants. This drives the need for harvesting and beneficiating landfilled ash as a replacement. High-quality harvested ash can be used similarly to fresh fly ash to replace some of the OPC in concrete. It offers the same level of performance while lowering the carbon footprint of construction and fostering circularity.

Additional alternative cementitious options include ground glass pozzolan made from glass waste streams and natural pozzolans sourced from natural mineral and volcanic deposits. The most common natural pozzolans used in concrete are calcined clay, calcined shale, and metakaolin. Other less widely used types include pumice, obsidian, and zeolites. A wealth of these different natural pozzolans is continually being evaluated within the industry to determine if they are readily available, cost effective, and meet targeted performance parameters.

Advancements in low-carbon concrete

From building property owners to government officials, stakeholders are increasingly focused on sustainable construction and the need to reduce the carbon footprint of the built environment. This has led to increased efforts among industry players in developing the next generation of high-performance, ultra-low-carbon concrete building materials that are more sustainable and circular.

Formulating these building materials is as much about following a rigorously defined process to achieve targeted performance as is it about applying scientific concepts to local raw materials characterization. For example, some low-carbon concrete mixes are custom designed with an innovative blend of SCMs and admixture technologies to provide high-performance properties with up to a minimum of 30 percent lower CO2 emissions than the U.S. industry average. These sustainable mixes can also be produced with construction demolition waste and other recycled aggregates to further enhance circular economy benefits.

Environmental impact reporting

Members of the design and build community—along with numerous green building standards and codes—are increasingly requiring transparent information on the environmental performance of construction materials. Manufacturers support this need with independently verified and certified environmental product declarations (EPDs) that offer a substantive characterization of environmental impacts at every step of a product’s life cycle. Defined by ISO 14025, these environmental “report cards” provide data on the GWP of cement and concrete materials to help specifiers make informed decisions.

As EPDs gain prominence in assessing environmental performance, they are increasingly requested in public and private building projects. They are also fundamental to low-carbon procurement practices. The Federal Buy Clean Initiative requires the use of low-embodied carbon building materials and the submission of EPDs for projects funded by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). If they are not already doing so, most state, county, and city Buy Clean legislative directives will soon follow suit by requiring this higher level of disclosure on the use of sustainable materials such as concrete in building projects.

Sustainable and resilient building projects

Concrete building materials are especially well-suited to provide protection against natural hazards and help ensure critical-service sites—such as hospitals, evacuation shelters, emergency operations centers, and data centers—can remain in operation even in the harshest of environments. The following are a few projects from across the country which have relied on innovative low-carbon mix design solutions to achieve ambitious sustainability, resiliency and performance goals.

Dallas

While the northward expansion of the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex brings many economic benefits, it also comes with certain challenges—especially considering North Texas is situated in “tornado alley.” As populations grow denser, communities must build high-performance concrete storm shelters providing critical structural resilience against high winds and flying debris during severe storms.

Owing to rapid development over the last several years, the city of Anna set out to develop a resilient 1,467-m2 (15,800-sf) central fire station and command-and-control center to serve as a safe room for emergency management professionals. One of the greatest construction challenges was the use of conventional concrete not being possible because the structure’s atypical shape and heavy reinforcement within the uniquely tapered 406-mm (16-in.) core walls did not allow for easy product placement and vibration.

Based on local raw-material assessments and rigorous quality control (QC) testing, the project team selected a self-consolidating concrete (SCC) per ASTM C1797, to meet the superior flow, optimal consolidation, bonding strength, low shrinkage, and 41,368-kPa (6,000-psi) strength requirements for providing the durability needed to ensure disaster-response services remained in operation in the most severe weather conditions.

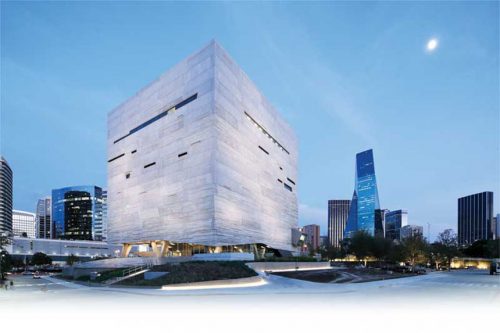

Sustainable and resilient construction practices in North Texas have gone far beyond emergency operations centers. The LEED Gold certified Perot Museum of Nature and Science in Dallas was awarded four Green Globes from the Green Building Initiative (GBI) for its sustainability practices.

The facade of the 16,722-m2 (180,000-sf) structure features 700 precast concrete panels with interesting, nuanced variations that impart high thermal mass to enhance energy efficiency, while the cast-in-place structural concrete walls provide strength, durability, and long service life.

To achieve the sustainable design and stringent performance requirements of the project, more than 17,584 m3 (23,000 yd3) of high-performance concrete mixes were used, containing up to 50 percent slag cement for the walls and up to 51 percent fly ash for the 1,625-mm (64-in.) diameter piers, 1.2-m (4-ft)-thick mat slab, support columns, and post-tensioned cantilever beams.

Denver

Colorado is working toward reduced emission targets of 50 percent by 2030 and 90 percent by 2050. Its Buy Clean Colorado Act helps the state meet these bold emission-reduction goals by using EPDs to drive the use of innovative low-carbon, energy-efficient, and high-performance building materials.

Slated to open in summer 2024, Populus—the country’s first carbon-positive hotel in downtown Denver—is using high-performance concrete with high-recycled content to maximize structural efficiency and help achieve LEED Gold status. This means the hotel will remove more CO2 from the air than it emits, resulting in negative carbon emissions.

Designed to meet stringent performance requirements and embodied carbon limits, the concrete used in the structure’s piers, footings, beams, and slabs consistently hit specified three-day early strengths and 28-day ultimate strengths, while achieving a 30 percent reduction in GWP. The project also used high-strength 55,158 to 62,052 kPa (8,000 to 9,000 psi), self-compacting concrete mixes in the columns and superstructure core walls to reduce element sizes and, in turn, lower GWP impact.

Of the many important climate issues, the increasing scarcity of fresh water commands some of the greatest attention in the American West. Denver is no stranger to the intensifying climate change impacts on water security. Its desert-like climate is dominated by ever-rising temperatures, low precipitation, and aridification—resulting in intense drought conditions and challenges in maintaining satisfactory moisture content to ensure proper curing of freshly placed concrete.

As the demand for water continues to grow, internally cured concrete6 is becoming a go-to solution for mitigating and adapting to climate change impacts. These innovative concrete mixes are designed with prewetted porous lightweight natural pozzolans (expanded shale and clay fines) as a partial replacement for sand to promote strength gain and the gradual release of moisture from within the concrete. This curing from the inside out increases durability and mitigates early-age cracking due to shrinkage and thermal stresses, along with curling and warping.

New Orleans

High-performance concrete is also taking center stage in projects on the Gulf Coast. In the wake of Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Ida, Southeast Louisiana has worked diligently to create a more durable, resilient, and sustainable built environment. Built to take nearly any punch nature can deliver, University Medical Center New Orleans—the only level-one trauma center in the region—serves as a model in resiliency for healthcare facilities around the country.

The sustainable concrete used in the 213,276-m2 (2.3-million sf), LEED-certified medical complex was designed with two different blended cements to help the structure endure hurricane-force winds up to 241 kmph (150 mph) and to meet flood-resistant construction standards. Due to the severe sulfate-rich soil on the site, 25,994 m3 (34,000 yd3) of concrete for the foundation slabs contained 50 percent slag cement to achieve long-term durability, high sulfate resistance, and a compressive strength of 48,263 kPa (7,000 psi). The resilient and eco-friendly design also relied on 57,341 m3 (75,000 yd3) of concrete containing fly ash for the beams, columns, elevated floors, and other structural applications.

Following hurricane Katrina, the new 90,301-m2 (972,000-sf) North Terminal at Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport (MSY) emerged as one of the most visible symbols of infrastructure rebuilding in the Gulf region. Designed to allow long spans, the spherical-shaped roof is supported by 350 massive concrete columns. Their construction required an innovative concrete solution that would flow easily through and firmly consolidate around highly congested embedded reinforcement, achieve a compressive strength of 48,263 kPa (7,000 psi), and deliver a class A exposed concrete finish.

To meet the stringent performance criteria for the challenging high-vertical structural support columns, the project team relied on a high-strength SCC mix containing high replacement levels of slag cement and fly ash to achieve the optimal flowability, control heat gain, and enhance compressive strength. The specified strength on this project was 48,263 kPa (7,000 psi); however, the custom SCC mix consistently achieved strengths of 75,842 kPa (11,000 psi) at 28 days.

Miami

The LEED certified Pérez Art Museum in Miami is situated on a breathtaking site overlooking Biscayne Bay, where frequent tropical storms or hurricanes and exposure to the corrosive sea air can cause serious problems for buildings. With a need for both aesthetics and resilience against hurricane-force winds, the architects relied on an ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) to produce approximately 100 long-span precast mullions to blend with the structure’s cast-in-place concrete elements and support the large curtain wall glazing that surrounds the building.

Blended with steel or organic fibers, UHPC enables the design of large complex shapes and very thin sections with longer spans, while providing resistance to hurricane-force winds, impact, abrasion, and corrosion. Due to its strength, UHPC made it possible to create thin, sinuous mullions up to 4.8-m (16-ft)-tall. This allowed unobstructed views over the museum’s veranda, while meeting the hurricane resistance standards of this tropical region and offering increased resistance to corrosion from the sea air.

Nike Miami—a two-story, 2,879 m2 (31,000 sf) retail establishment in Miami Beach—also relied on UHPC to produce the building’s perforated brise-soleil facade system. This intricate casting filters light to the interior of the store to reduce heat gain from the hot South Florida sun. The durability, resilience, and ductility of the 180 UHPC precast panels ensure this facade will stand the test of time in an area frequently exposed to extreme heat and tropical storms, while improving energy efficiency in harsh subtropical climate conditions.

Minneapolis

Minneapolis has been striving to reduce GHG emissions for 30 years. With countless building projects underway, engineers, architects, and developers drive the demand for low-carbon construction solutions to support the city’s commitment to the U.S. Mayors’ Climate Protection Agreement for reducing GHG emissions.

The construction of the 42-story Eleven on the River residential condominium in the heart of Minneapolis utilized 28,288 m3 (37,000 total yd3) of high-performance concrete. Specified strength targets included 41,368 kPa (6,000 psi) and 55,158 kPa (8,000 psi) for post-tensioned decks and 68,947 kPa (10,000 psi) and 82,737 kPa (12,000 psi) for walls and columns. To achieve stringent requirements for modulus of elasticity, a high-performance concrete was used to limit sway of the tall, slender structure. The low-carbon concrete used in the tower provided a 32 percent reduction in CO2 emissions.

The journey ahead

If the built environment does not significantly reduce the embodied carbon of construction materials while simultaneously adapting to shocks or stresses of an already-changing climate, the industry will continue to experience serious cascading effects on the environment, economy, and wellbeing of local communities.

The development of concrete mix designs is a balancing act with performance, sustainability, and economics. SCM changes are accelerating quickly and natural pozzolans—which act differently and may require more water, admixtures and/or other mix adjustments—are becoming more available. To fully harness the significant potential of innovation for decarbonizing the built environment, the best strategy is to shift from a prescriptive specification to a performance-based approach that is free of limitations on the composition of the concrete mixture, such as minimum cement content, limits on types and replacement levels of SCMs, maximum water-cement (w/cm) ratios, and other constraints. This shift in emphasis will help make mixes more sustainable, cost effective, and easier on the entire process of batching, transporting, placing, and finishing while maintaining performance.

As the industry progresses on its journey to achieving a more sustainable and resilient built environment, collaboration across the entire value chain remains crucial to success. Best practices include engaging cement and concrete producers early in the project planning phase to discuss specified performance requirements, establishing a carbon budget for all the concrete used in the building, evaluating various cementitious material options, and reviewing supporting EPD documents for meeting GWP reduction targets.

Notes

1 Refer to the CO2 Emissions in 2023 report by the International Energy Agency (IEA) at www.iea.org.

2 Read the article, “WMO Confirms That 2023 Smashes Global Temperature Record” by World Meteorological Organization at https://wmo.int/news.

3 Review “Why the Built Environment?” by Architecture 2030 Challenge at www.architecture2030.org.

4 Refer to “Global building sector CO2 emissions and floor area on the Net Zero Scenario, 2020-2050” by the International Energy Agency (IEA).

5 For more information, see “FORTIFIED Commercial Program” by Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety (IBHS) at www.fortifiedhome.org/fortified-commercial.

6 Guide specifications for internally curing concrete can be found on the National Concrete Pavement Technology Center’s website.

Authors

very informative…..like it

Processing of limestone for Portland Cement requires calcining (cooking) of limestone converting it from calcium carbonate to calcium oxide (quick lime). This process gives off carbon dioxide. How does an increased content of limestone in PLC (Portland Limestone cement) reduce the carbon footprint?