By Amy Becker

Specifiers and design professionals should always consider seismic performance attributes for buildings in areas that previously have experienced the damaging effects of earthquakes. After seismic activity has occurred, building occupancy and soil conditions may lead to seismic mitigation even if there is no

visible damage.

To help buildings perform their best under some of the worst conditions, it is important to understand the current codes and standards, what happens during an earthquake, how to prove fenestration and glazing products meet code and specified requirements, and how performance-based research can continue to contribute to resilient buildings that protect people.

Shifting codes and standards

Aging and/or poorly engineered buildings are among the leading causes of increasing damage and losses from earthquakes in the United States—annualized losses from earthquakes nationwide total $6.1 to $14.7 billion annually.

Building codes are adopted with the intent to preserve life and safety. Their recent developments have focused on bolstering “community resilience” and “functional recovery,” resulting in increased seismic considerations in construction. This has shifted the discussion from general safety to a building’s functionality, serviceability, and operation after an event and moved the attention from being on the structure to the building’s occupants.

As more is learned about seismic events and how their characteristics could be better measured, the ability to design and construct better-performing buildings increases. Today’s metrics include loss of life, cost in dollars, and downtime length—otherwise referenced as life safety, performance level, and functional losses. Effectively using this data and the historical effects of earthquakes allows for a research-driven approach to mitigate future damage and build resilient structures. A benefit of learning about seismic events is greater collaboration for information sharing across academic, governmental, and commercial organizations.

Building standard requirements have improved through research, data collection, and analysis. This includes updated criteria for the most widely used standard: the American Society of Civil Engineers/Structural Engineering Institute’s ASCE/SEI 7-22, Minimum Design Loads and Associated Criteria for Buildings and Other Structures.

Seismic design criteria

During an earthquake, seismic forces ripple from their center like waves on still water. The characteristics of these forces can be measured by:

- Ground acceleration

- Velocity

- Displacement

- Duration

- Magnitude

Depending on the size of the seismic force’s “wave,” a building moves in response and then jerks back. During this, the building exhibits “racking,” where it moves back and forth, and “jacking,” where it moves up and down. How these forces affect buildings and structures depends on:

- Distance from the active earthquake zone

- Original design of the building

- Function of the spaces

- Composition of soils beneath the building

Ideally, the building’s structure holds together, but great movements can cause serious damage to the structure and all the components attached to and inside of it. These elements are typically broken into two areas:

- Structural elements—A piece of a structure used to support the structure’s weight and its supported contents and attachments. It is also used to resist various types of environmental loads, including earthquakes and wind. These include columns, joists, purlins, load-bearing walls, floor slabs, and foundations.

- Nonstructural elements—Components of a building not designed to contribute to its structural resistance. These include architectural and MEP systems, furniture, fixtures, equipment, and other contents. Fenestration and glazing products are considered “architectural components” and are categorized as nonstructural building elements.

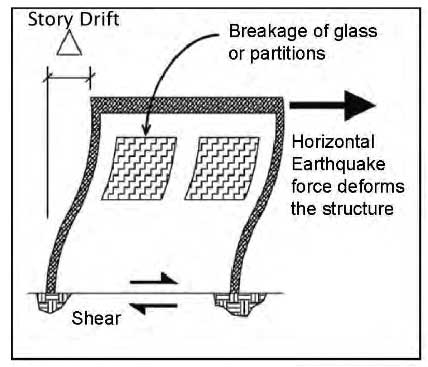

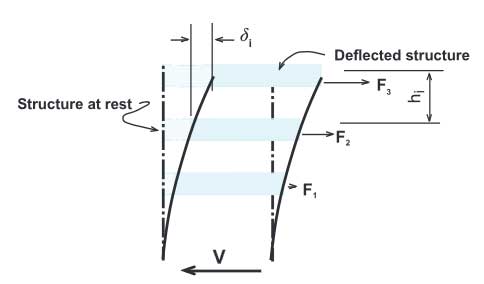

When seismic forces impact a building along its horizontal, lateral plane, the opposing movements result in ground-level shear that can deform structural and nonstructural elements. The change in a building’s original alignment at rest to its deflected state after being subjected to lateral earthquake forces is referred to as inter-story drift. The shear force and inter-story drift can cause breakage of a building’s fenestration, glass, glazing partitions, and related components.

While all new structures must have lateral force resisting systems and have structural integrity, seismic design criteria range from the general ability to resist seismic forces to include items such as:

- Seismic-resistant components

- Protection of noncritical systems for life safety

- Nonstructural components capable of functioning post-earthquake along with quality-assurance (QA) measures

- Nonstructural components that must be restrained

Recently updated seismic design criteria have been adopted into the 2024 edition of the International Building Code (IBC) to improve building performance and safety. In large part, these criteria are based on three factors:

- Occupancy or Risk Categories I to IV, with Category I representing no or low human occupancy, to Category IV representing critical occupancies such as hospitals, and high risks such as places that store hazardous materials. These categories even extend to post-event management. For instance, a home for older adults will have its damage addressed before a general office building because the occupants are able to support lesser being without a residence.

- Site Class A to F, where Class A is highly stable, hard rock, and Class F is highly unstable, volatile soil.

- Seismic Design Categories (SDCs) A to F, with SDC A representing a small probability and SDC F representing a high probability to critical structures near active faults.

With IBC 2024, specification professionals and building teams now have a choice to use either the provisions of ASCE/SEI 7-22 or the IBC’s SDC maps. While ASCE/SEI 7-22 is used for both the IBC and the International Residential Code (IRC), their seismic design criteria are not interchangeable, and their SDC maps differ.

For existing buildings, ASCE/SEI 41-23, Seismic Evaluation and Retrofit of Existing Buildings, offers similar calculations to ASCE/SEI 7 with more analysis of whether components can accommodate seismic loads and inter-story drift.

Fenestration failure prevention

In an earthquake, nonstructural building elements can cause damage and life-safety hazards, resulting in significant costs and losses. For example, if fenestration and glazing are above egress paths, breakage can produce falling glass. A building component’s weight, attachment to the surrounding structure, location in proximity to occupants, and how it fails are key to improving stability and functionality and reducing damage and destruction.

Fenestration and glazing assemblies are sensitive to accelerations and deformations and are subject to in-plane and out-of-plane failures. Glazing is particularly vulnerable in flexible structures with larger inter-story drifts, and large storefront windows are also vulnerable.

The following are some main ways fenestration and glazing fail during earthquakes:

- The glass remains broken but continues to stay in its frame or anchorage.

- The glass cracks but remains in its frame or anchorage while continuing to be a weather barrier.

- The glass shatters but remains in its frame or anchorage in a precarious position, liable to fall at any time.

- The glass falls out of its frame or anchorage. Glass can fall in shards, shatter into small pieces, or broken panes may be held in place by film.

Glazing that stays in place is the best-case scenario. The building is more likely to be occupied and operational again. People are protected in terms of safety and weather. Nothing falls on anyone or blocks the exit door. There are additional advantages with laminated glass—even if it does break, the laminated film will hold the glass pieces together.

Be aware that many reasons for fenestration failures and glazing performance issues in earthquakes are a result of poor installation techniques. These include failure to provide clearances, use of improper shims, and failure to hold dimensional tolerances.

To ensure compliance with codes and standards, fenestration and glazing demonstrate proven performance, the Fenestration and Glazing Industry Alliance (FGIA) recently improved its AAMA 501-24, Methods of Test for Exterior Walls, and test specification standards with respect to ASCE/SEI 7-22.

AAMA 501 offers a comprehensive document addressing laboratory and field test specifications for metal curtain walls, including performance characteristics, test specimens, methods, recommended practices, test apparatus, and testing procedures.

Manufacturers and installers of fenestration products and glazing assemblies rely on FGIA’s supplemental test method documents for seismic performance addressing:

- AAMA 501.4, Recommended Static Test Method for Evaluating Window Wall, Curtain Wall and Storefront Systems Subjected to Seismic and Wind-Induced Inter-Story Driftt—This describes methods to test lateral movement, including racking and twisting of one story relative to the adjacent story. It provides a means of evaluating the performance of fenestration systems when subjected to horizontal displacements in the plane of the wall and focuses on their usability regarding air infiltration, water penetration, and structural integrity.

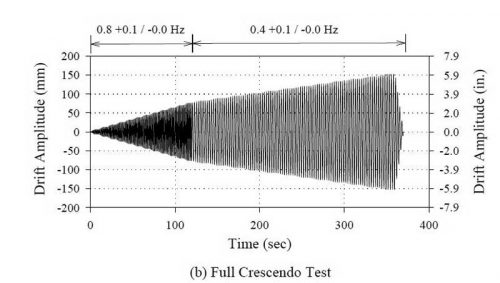

- AAMA 501.6, Recommended Dynamic Test Method for Determining the Seismic Drift Causing Glass Fallout from Window Wall, Curtain Wall and Storefront Systems—This describes test methods to evaluate the components of the overall glazing system. Also known as the crescendo test, static loads are applied in cycles of the increasing amplitude determined from a percentage of expected inter-story drift during an earthquake to determine if there is glazing fallout. This test also may uncover issues regarding the relationship between the glazing and adjacent components.

- AAMA 501.7, Recommended Static Test Method for Evaluating Windows, Window Wall, Curtain Wall and Storefront Systems Subjected to Vertical Inter-Story Movements—This describes methods to test vertical movement, including jacking up and down of one floor relative to the adjacent floor. It provides a means of evaluating the performance of fenestration systems when they are subjected to vertical displacements and focuses on their usability regarding air infiltration, water penetration, and structural integrity.

Insulating glass unit manufacturers and fabricators also typically follow FGIA’s IGMA TB-1200 guidance, “Guidelines for Insulating Glass Dimensional Tolerances.” This document outlines glazing cavity size, allowable edge seal pressure, setting block type, allowable minimum edge seal system, and sightline design requirements.

Resilience and research

Current building code provisions prioritize resilience and serviceability. When designed and constructed to preserve functionality, people are more likely to survive the event and return quickly to their daily lives.

To ensure a building’s structural integrity, the effects of inter-story drift must be limited. For structural building elements, limits are moving away from minimal life-safety requirements. On the lateral system, this includes tighter limits on inter-story drift. For nonstructural building elements, the emphasis is on ensuring spaces are less dangerous for occupants during the event and for their egress when leaving the building. Nonstructural components may be damaged, but they should not be life-threatening.

Continuing research on nonstructural elements gives insight into how building components interact and how to remediate the risks associated with earthquakes. As research improves, building code criteria, standards, and tests can improve, and buildings can become safer for their communities.

Providing research to drive continued improvement, the University of California San Diego (UCSD) is home to Englekirk Structural Engineering Center, which has the largest outdoor earthquake simulator in the world. It is one of the first large-scale laboratories accredited to meet the International Organization for Standardization and the International Electrotechnical Commission, ISO/IEC 17025, “General requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories.” UCSD’s outdoor site includes a massive three-axis shake table that tests real-life simulations at scale and well beyond controlled laboratory conditions.

The Natural Hazards Engineering Research Infrastructure TallWood Project is the largest test of its kind conducted at UCSD. It incorporated a focus on fenestration and glazing components and systems. The full-scale, 10-story building was constructed on top of the shake table.

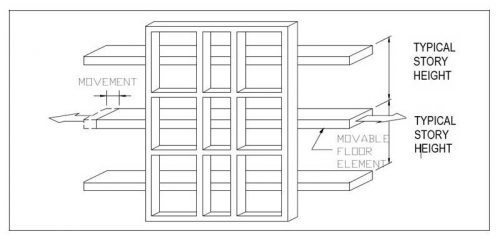

Its exterior facade consists of four subassemblies at the base of the building, all of which are attached to the main wood-framed structure. The first three subassemblies feature cold-formed steel (CFS) framing with an exterior aluminum composite finish and windows, while the fourth is a curtain wall. All are detailed for inter-story drift compatibility by providing horizontal and vertical joints.

- CFS 1: This subassembly is platform framed with horizontal slip joints at the top of the wall, provided by either nested tracks or a horizontally slotted top track. Slip was intended to occur between the two nested tracks or between the slotted track and the floor slab. The corner used special gasketed joints that expand. The same joint was used on two of the three stories. The third story without the joints serves as a reference so the researchers can compare the performance with and without joints.

- CFS 2: This subassembly was bypass framed with drift clips that allow the studs to slip relative to its diaphragm. The floors were expected to move and the walls to remain straight. A large, hinged joint accommodated up to 254 mm (10 in.) of relative movement at the corner.

- CFS 3: Featuring metal spandrel units with ribbon windows, this subassembly also had slip joints at the top of windows and the bottom of the spandrels, while the spandrel framing was fixed to the diaphragm. The first and third stories use windows that wrap around the corner. On the second story, an expansion joint was used at the corner, similar to CFS 1.

- CFS 4: This final subassembly was a finished, fire-rated curtain wall assembly with rotating glass within its frame. It had steel mullions and 27 mm (1.06 in.) of thick, fire-rated glass and was framed on site.

Beneath the building’s full-size mock-up sits the shake table itself. Actuators drive the shake table platform in all directions. The table moves a maximum of 889 mm (35 in.) in the East-West direction, 381 mm (15 in.) in the North-South direction and 127 mm (5 in.) up and down. At a payload capacity of 452 tonnes (499 tons), about twice that of the timber building, the peak acceleration capacity is 1.6g, 1.2g, and 0.6g (“g” referring to the acceleration of gravity at Earth’s surface is equal to 9.81 m/m2) in East-West, North-South, and vertical directions, respectively.

Over four weeks, 88 shakes were conducted with variations in source type, intensity, and directions. A typical building designed for life safety would be expected to incur significant damage after a single strong shake, and such a rigorous test program would not be possible. The building was designed to be resilient, thus sustaining repeated strong shaking. The results showed these fenestration systems performed well, demonstrated significant capacity to accommodate inter-story drift, and achieved the resilience objectives.

Understanding seismic codes, standards, test methods, and research on fenestration and glass performance assists specifications professionals in ensuring people’s life safety, minimizing property damage, and reducing overall loss from earthquake events. More than that, understanding the “natural” aspects of a natural disaster can take us all a step further in truly transforming the “disaster” aspects.

Resources

View resources online at the constructionspecifier.com/fenestration-glazing-seismic-performance

Test Your Knowledge! Take Our Quiz!

Author

Amy Becker is the glass products specialist for the Fenestration and Glazing Industry Alliance (FGIA). She oversees the operation of the Insulating Glass Certification Council, Insulating Glass Manufacturers Alliance (IGCC/IGMA), and Insulating Glass Manufacturers Association of Canada (IGMAC) certification programs. She serves as the internal auditor for FGIA fenestration certification programs. With more than 20 years of industry experience, Becker is also a staff liaison for the association’s glass-focused committees and task groups and represents FGIA and its members at meetings of other industry organizations. She can be reached at abecker@FGIAonline.org.