Choosing between restoring or replacing cracked, spalled, and displaced brick facades

For extreme conditions, maintenance or restoration may not be sufficient and the brick will have to be replaced. This is necessary when the brick’s bearing or lateral stability is compromised. The following case studies examine situations which call for maintenance, restoration, or a full assembly replacement.

Case study 1: Wear and tear

An elementary school building constructed in multiple phases has a red brick facade. The majority of the facade has little deterioration, except on a mortar joint step crack on one of its abandoned chimneys. The building appears to have adequate movement capabilities for the brick, and the cracking is likely related to the use of the chimney and the furnace-related temperatures it was subjected to. Since the chimney is no longer in use and the rest of the brick is performing well, no other movement provisions are required for this repair. Solely repointing the mortar crack is appropriate for this condition.

Case study 2: Relieving angle turned into a lintel

A university building was constructed in the mid-1950s with a red brick masonry cavity wall and a concrete superstructure. The cavity wall is typically 13.7 m (45 ft) tall and is dead loaded at the base of the structure (i.e. with no floor line relieving angles). It appears as though lintels existed above windows openings and extended 0-152.4 mm (0 to 6 in.) into the adjacent masonry. Figure 4 shows a typical elevation.

No movement provisions were provided at this building. Experts observed step cracking at window opening corners. They investigated these cracks by making exploratory openings, and what they found shocked them.

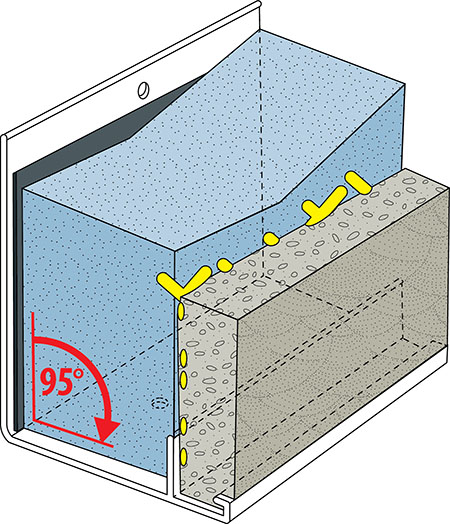

The relieving angles were set into shelf angle wedge inserts (Figure 5).

Some of these lintels also extended up to 152 mm (6 in.) into the adjacent masonry piers. As the masonry grew due to moisture and thermal expansion, and the superstructure shrank due to concrete shrinkage, the masonry began lifting the relieving angle until the relieving angle support bolts hit the top of the wedge insert, turning the renovators’ relieving angle into a lintel. In some cases, the masonry continued to grow, lifting the masonry above the windows so it no longer bore on the newly converted steel angle.

Renovators came up with the following criteria to correct the issue:

- Bearing ≥ 25.4 mm (1 in.)—Do not modify the angle. As long as the bearing condition is greater than 25.4 mm (1 in.), the masonry piers can withstand the load imposed by the lintel.

- 0.0 mm (0.0 in.) < Bearing < 25.4 mm (1 in.)—Remove and replace the angle, provide a bearing of 101.6 mm (4 in.) minimum. If the bearing condition is less than 25.4 mm (1 in.), the masonry is at risk of crushing and spalling. Incidentally, renovators did not observe many of these conditions as the masonry had already spalled.

- Bearing < 0.0 mm (0.0 in.)—Do not modify the angle. If the angle never bears on masonry or if the masonry has spalled and is no longer there to bear on, the angle is simply bearing on the wedge insert and is back to being a reliving angle as the original designers intended.