Circulating good indoor air quality

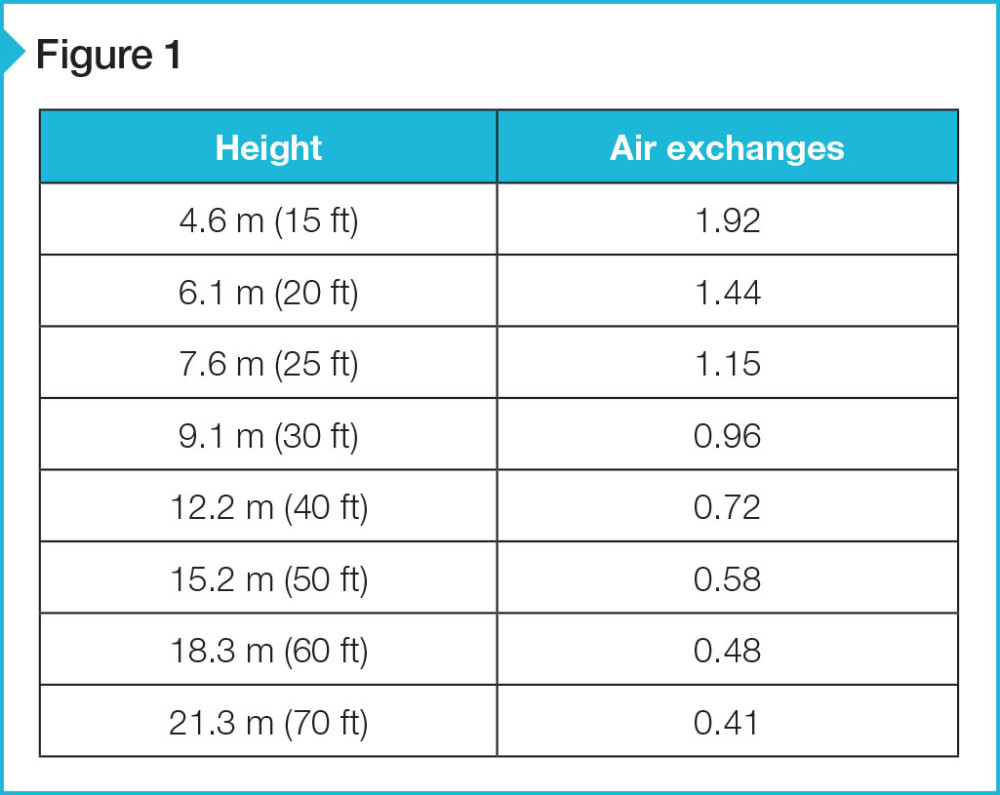

Proper ventilation levels vary based on local code, system/space requirements, and engineering calculations. Figure 1 converts a minimum recommended value into air exchanges per hour (volume of air in space/volume of outdoor air provided in one hour). American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) 62, Ventilation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality, requires a minimum of 2.4 L/s/m2 (0.48 cfm/sf) of floor area for swimming pools.

Air movement at work

The University of Texas at Austin is home to one of the first large-scale university aquatic facilities built in the United States. Modeled after the facility used for the 1972 Olympics in Munich, Germany, the Texas Swim Center recently met the challenges of improving IAQ with an impressive ventilation system upgrade and the addition of large-diameter, low-speed fan technology. Using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modelling—a computer simulation of airflow—engineers and facility managers were able to define a system that provides comfort as well as improves air quality.

“We used a carbon gas-space filtration, and increased the amount of outside air we bring in, not just re-circulated the air we have in there,” says Charles Logan, the university’s swim center director.

To aid this process, four 7-m large-diameter, low-speed ceiling fans were installed from the 14-m (45-ft) high ceiling throughout the pool complex.

“We have a daily setting for these fans, but at night when we don’t have anybody in the facility, three things happen,” Logan explains. “[Air] release valves open up in the building, the fans are turned up to full speed, and 100 percent outside air is brought in to flush out all the air that circulated throughout the day.”

This is in contrast to air re-circulators that move around the contaminated air in the space with virtually no way for it to escape.

Shawn Allen, an engineer with José I. Guerra Inc., helped design the new system. He said the total volume of air movement was established based on the calculated evaporation rate of water in the space, taking into consideration the vapor pressure of the pool water and air at design temperature.

Allen explained air is returned from the pool deck to one of five separate units where the air passes over a carbon-impregnated filter bank to remove chloramines and is cooled by a chilled water coil below saturation temperature to induce condensation and remove water from the air. Once the air is cooled, it is then passed over a hot-water reheat coil, using recovered heat, which brings the air back up to a discharge air setpoint modulated based on each individual space thermostat. The air leaves each unit free of chloramines, dry, and at any range of required temperature as established by space requirements.

Comfort component

In the summer, large-diameter, low-speed fans provide a cooling effect, moderating the environment for spectators and those milling around the deck. In facilities that must contend with extreme cold in the winter, heating system efficiency is also drastically improved by providing destratification—bringing fresh air trapped at the ceiling level down to the occupants. Heated air from a forced air system (i.e. 38 to 52 C [100 to 125 F]) is less dense than the ambient air (i.e. 24 to 29 C [75 to 85 F]) and naturally rises to the ceiling.

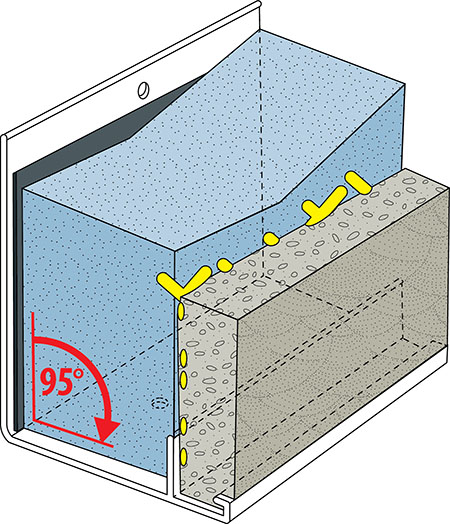

Large-diameter, low-speed fans reduce temperature variations between the floor and ceiling, mixing the warm air trapped at the ceiling with the cooler air at the pool level. Slowing the speed 10 to 30 percent of its maximum rotations per minute (RPM), the warm air is redirected from the ceiling to the occupant level, increasing patron comfort and reducing the heat loss through the roof. At the same time, the fans can be tied in with a facility’s automation system, allowing facility managers to control all their systems together, fluctuating along with capacity, which is critical when it comes to keeping swimmers comfortable outside the water as well.

Ductwork

With large-circulator fans assisting the airflow, the university was able to eliminate ductwork altogether, significantly reducing upfront material and labor costs. According to ASHRAE, failure to deliver airflow at the pool deck and water surface leads to IAQ issues—a primary impetus in many of today’s upgrades. To circumvent this issue, large fans destratify the air, mixing the warm air accumulating at the ceiling with the cool conditioned air, resulting in uniform temperatures. (See the 2011 American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-conditioning Engineers [ASHRAE] Handbook–HVAC Applications.)