Clearing specifiers’ misconceptions about lightweight concrete

Hayde’s findings on ESCS aggregate were quickly employed in concrete ship construction during the World War I.1 Since the material created a consistently high strength and lightweight concrete, it helped bolster the increased need for durable ships due to submarine warfare. It did not take long to recognize the material’s economies in commercial building. In 1928, the vertical expansion of the Southwestern Bell office building in Kansas City, Missouri, was one of the earliest applications of lightweight concrete for buildings in the U.S. Lightweight concrete allowed designers to almost double the number of stories added to the building.

By the 1950s, structural lightweight concrete—considered for the remainder of this article as concrete using a mixture of Portland cement, water, fine sand aggregates, and ESCS coarse aggregates—had gained general field acceptance. This mix was standardized by the ASTM based on testing the material to find the best strength-to-weight ratio. The material proved effective at reducing the deadload of concrete structures while offering a high degree of insulation, nominal shrinkage, comparable compressive strength to normal-weight concrete, thinner concrete slabs for the same fire rating and more.2

Today, many of the benefits listed above are well understood in commercial building construction. However, some building professionals and specifiers question how this material performs as a component of composite metal floor or roof slabs and what its limitations are. Most of these questions center around its lightweight and porous form, and how those qualities impact end-use performance. Answering these questions not only demystifies the material and its specifications but also highlights its benefits within the built environment when compared to normal-weight concrete.

Does the absorption capacity of aggregate material alter performance capabilities?

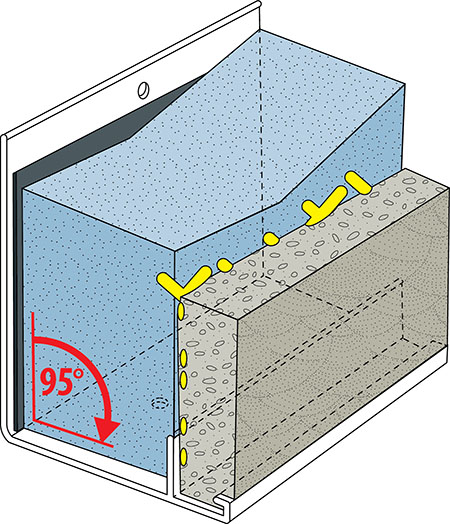

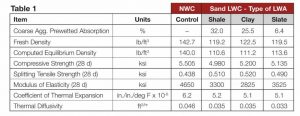

As discussed earlier, the rotary kiln process used to manufacture lightweight aggregates creates an unconnected internal pore network, reducing the aggregate’s density. When fully submerged in water for over 48 hours, some expanded lightweight aggregate types will absorb significantly higher percentages of water, by mass, than other types (Table 1). Since some may argue a high absorption capacity belies a high degree of permeability (thus an increased likelihood a fluid could penetrate and compromise the concrete’s chemical stability), it may seem natural to conclude that structural lightweight concrete made from aggregates with greater absorption potential would have reduced performance properties. However, data from a study performed by Byard and Schindler at Auburn University (2010) indicates the raw material from which the aggregate is manufactured has little bearing on performance outcomes.3 This means a lightweight aggregate’s ability to absorb moisture does not affect its ability to resist permeability once cured.