Clearing specifiers’ misconceptions about lightweight concrete

by arslan_ahmed | January 20, 2023 10:00 am

[1]

[1]By Ken Harmon

Despite having well-documented performance capabilities, lightweight concrete often conjures several questions in the minds of specifiers. From its lead times to cost, unanswered questions can cause some professionals to steer away from the material, even when its use would enhance the building’s design and support cost-savings to the project’s bottom line. In addition to providing an overview of the development of lightweight concrete, this technical article answers three commonly asked questions to inform construction specifiers on what they can expect from the material in terms of application, performance, and overall cost.

How did lightweight concrete come to be?

When Stephen J. Hayde began experimenting with lightweight concrete aggregates made of expanded shale, clay, or slate (ESCS) in the early 1900s, he set out to solve a perennial industry problem: how to reduce the bloating of brick as it expands when subjected to high heat during the burning process. Hayde discovered both the temperature rise times and material composition play a role in determining if a brick will bloat or not. These findings contributed to a more efficient brick making process. However, Hayde’s discoveries had a far wider reach than brick productions.

Hayde determined when shale, clay or slate is heated to approximately 1093 C (2000 F) during a rotary kiln process, the lightweight aggregate softens and forms bubbles which remain as pores when it cools. The pores within the vitrified ceramic aggregate particles result in a strong material with reduced density. When crushed, this material can be added to concrete mixes to reduce deadloads and improve the performance of concrete.

Hayde’s findings on ESCS aggregate were quickly employed in concrete ship construction during the World War I.1 Since the material created a consistently high strength and lightweight concrete, it helped bolster the increased need for durable ships due to submarine warfare. It did not take long to recognize the material’s economies in commercial building. In 1928, the vertical expansion of the Southwestern Bell office building in Kansas City, Missouri, was one of the earliest applications of lightweight concrete for buildings in the U.S. Lightweight concrete allowed designers to almost double the number of stories added to the building.

By the 1950s, structural lightweight concrete—considered for the remainder of this article as concrete using a mixture of Portland cement, water, fine sand aggregates, and ESCS coarse aggregates—had gained general field acceptance. This mix was standardized by the ASTM based on testing the material to find the best strength-to-weight ratio. The material proved effective at reducing the deadload of concrete structures while offering a high degree of insulation, nominal shrinkage, comparable compressive strength to normal-weight concrete, thinner concrete slabs for the same fire rating and more.2

Today, many of the benefits listed above are well understood in commercial building construction. However, some building professionals and specifiers question how this material performs as a component of composite metal floor or roof slabs and what its limitations are. Most of these questions center around its lightweight and porous form, and how those qualities impact end-use performance. Answering these questions not only demystifies the material and its specifications but also highlights its benefits within the built environment when compared to normal-weight concrete.

Does the absorption capacity of aggregate material alter performance capabilities?

[2]

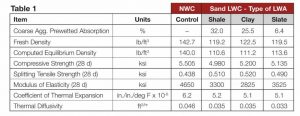

[2]As discussed earlier, the rotary kiln process used to manufacture lightweight aggregates creates an unconnected internal pore network, reducing the aggregate’s density. When fully submerged in water for over 48 hours, some expanded lightweight aggregate types will absorb significantly higher percentages of water, by mass, than other types (Table 1). Since some may argue a high absorption capacity belies a high degree of permeability (thus an increased likelihood a fluid could penetrate and compromise the concrete’s chemical stability), it may seem natural to conclude that structural lightweight concrete made from aggregates with greater absorption potential would have reduced performance properties. However, data from a study performed by Byard and Schindler at Auburn University (2010) indicates the raw material from which the aggregate is manufactured has little bearing on performance outcomes.3 This means a lightweight aggregate’s ability to absorb moisture does not affect its ability to resist permeability once cured.

[3]

[3]The study compared the performance of lightweight concrete using lightweight aggregate made from three sources: a shale, a clay, and a slate. Three mixtures were made using each lightweight aggregate type:

- An internally cured mixture for which a fraction of the conventional fine grade aggregate (sand) was replaced with prewetted lightweight aggregate.

- A sand lightweight concrete mixture, for which lightweight coarse aggregate and conventional fine aggregate (sand) were used (this is the most commonly used type of lightweight concrete).

- An all-lightweight concrete mixture, for which all of the aggregate was lightweight and, therefore, gave the lowest possible density.

All three types of lightweight aggregate met the requirements of American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) M 195 or ASTM C330, Standard Specification for Lightweight Aggregates for Structural Concrete. However, to simplify the discussion, only the sand lightweight concrete data are presented in the table. The performance qualities of a normal-weight concrete made from river gravel acts as a control.

In looking at the results, the shale and clay lightweight aggregate evidently have higher absorption percentages than the lightweight aggregate made from slate yet display similar attributes. The answer to this question is no. The absorption capacity of a raw material does not alter the performance qualities of lightweight concrete as this water is used for internal curing and does not contribute to structural loads post curing. In fact, only minor differences exist between the 28-day compressive and splitting tensile strength data for the shale and clay aggregates and the slate aggregate. Further, the slate aggregate’s splitting tensile strength is the lowest of the three mixtures, despite its low absorption percentage.

Considering the minor differences between lightweight and normal weight concretes, it is interesting to note the absorption percentages do not seem to indicate a linear relationship to performance qualities. Given normal-weight concrete has an absorption capacity of one to two percent, it would indicate how it is the most similar to slate and least similar to shale, all things considered; yet this is not the case. The differences between the materials do not seem related to absorption capacity in a predictable way. Therefore, it can be reasonably concluded the absorption rate of the aggregate does not primarily drive structural lightweight concrete’s strength and durability.

Does it take longer for lightweight concrete to dry?

Lightweight aggregate has a higher absorption capacity than conventional aggregates. Its internal pore network absorbs and stores water before gradually releasing it over time. It is also prewetted prior to placement to maintain slump and allow pumping. For all concrete, water will evaporate until the slab achieves an equilibrium with ambient conditions. Therefore, lightweight concrete would take longer to dry because it absorbs more water.

As a slab dries, evaporating water can bring alkalinity to the surface and interact with some flooring adhesives, especially those which are water-based, causing scheduling delays or flooring defects. To avoid this problem, test the moisture of the slab before installing any adhesive or flooring. Contractors can use the calcium chloride test, per ASTM F1869-11, or a more comprehensive relative humidity test, per ASTM F2170-11, at any point after the slab has cured to a point to allow foot traffic. This can be as soon as seven days and as long as 60 days after pouring. Since different flooring systems have different moisture tolerances, it is best practice to compare the testing results with the parameters of the flooring being used before application.

This was verified under laboratory conditions in a 2000 study conducted by Suprenant and Malisch.4 The study asserted how, compared to normal-weight concrete slabs, lightweight concrete slabs of the same dimensions took more than four-and-a-half months longer to reach a moisture vapor emission rate (MVER) of 1.36 kg (3.0 lb) per 304.8 m2 (1000 sf), every 24 hours. However, the results of this laboratory study did not seem to accurately represent field experiences, such as changing ambient conditions and minimum slab thickness to satisfy code requirements.

To understand the differences between the laboratory results and experiences in the field, the Expanded Shale, Clay, and Slate Institute (ESCSI) sponsored a study conducted by Peter Craig, an instructor for the International Concrete Repair Institute (ICRI) moisture testing certification program, to assess more closely the drying times of lightweight concrete slabs. The study sought to accurately represent field conditions and slab thicknesses required to satisfy Underwriters Laboratories (UL) No. D916 for a two-hour fire-rated assembly.5 Slab drying was monitored using two methods: ASTM F1869 and ASTM F2170.

Based on the results reported in the ESCSI study, which conducted direct comparisons between lightweight and normal-weight concrete slabs, the answer to this question is more complicated than a simple yes or no. While the testing needs further investigation to substantiate its claims, it seems to reveal two important distinctions between lightweight and normal-weight concrete drying timelines: amount of material needed to satisfy fire ratings differs and the environment plays a larger role in drying than initial water content.

Lightweight concrete does have a higher moisture content than the normal-weight concrete, and if the two types are compared in equal dimensions, then normal-weight concrete will reach acceptable MVER levels quicker. However, to achieve a two-hour fire rating, an assembly requires 29.5 percent more normal-weight concrete thickness than lightweight concrete. The additional water-of-convenience needed for more concrete brings the total initial water levels closer together. When placed to a thickness able to satisfy fire-safety code requirements, lightweight concrete assemblies contained only 11.3 percent more water than normal-weight concrete assemblies. The difference in water quantity is not significant enough to produce a substantial change in drying times.

By recreating field conditions (including reduced slab thickness and recreating ambient humidity conditions), the study suggests the ambient environment poses a greater role in slab drying. Placed in a warehouse which was not climate controlled, neither the lightweight nor the normal-weight slabs consistently held the MVER limit. This implies rewetting from rainwater or relative humidity (RH) in unsealed buildings has more influence on drying timelines than initial water content. Until a structure is enclosed, a concrete slab of any type cannot begin to dry. Therefore, one can expect both lightweight and normal weight concretes will require flooring adhesives that are capable of working on a higher moisture substrate or some mitigation technique to address the potential for moisture contents in concrete slabs greater than the industry limits.

In short, volume to volume comparisons of normal-weight and lightweight concrete in laboratory conditions indicate normal weight will dry more quickly. However, when reduced slab thickness and ambient humidity of a site are taken into account, the drying times between concretes becomes less significant.

Is lightweight concrete more expensive to use?

Since lightweight concrete made with ESCS aggregate incurs additional production and shipping costs, many assume this material is not an economic solution for a multi-story or high-rise building. While this is certainly true if only the cost of materials were compared, the use of lightweight concrete reduces costs in other areas of the building design. It satisfies fire ratings with thinner slabs, provides longer spans due to increased tensile strength,6 and reduces load weight for beams, columns, and foundations (for instance the 55-story Bank of America building reduced floor weight by 32.5 percent by using structural lightweight concrete instead of normal- weight concrete). Though the increased tensile strength impacts bridge and pavement projects most, its benefits extend to building construction as well. With all the above qualities, lightweight concrete can not only offset its increased per cubic meter cost but can also lead to significant overall savings regardless of geographical location.

| UNDERSTANDING EMBODIED ENERGY AND EMISSIONS OF A MATERIAL |

| While many construction specifiers understand the performance and cost benefits of structural lightweight concrete, these are not the only aspects to consider when deciding between building materials. Understanding the embodied energy and emissions of a material can help professionals reach a project’s sustainability and net zero emission goals.

Since lightweight coarse aggregate needs to be produced in a high heat rotary kiln, its material energy can be nearly 30 times greater than normal-weight aggregates. This would cause many to consider lightweight concrete a less sustainable option than normal-weight concrete, precluding its use in sustainability-minded buildings. However, lightweight concrete can be poured in thinner slabs with lower densities and thus reduce the material needs of other systems. When looking at a five-story building completed and studied by Walter P. Moore and Associates for the Expanded Shale, Clay and Slate Institute (ESCSI), this quality created a 1.4 percent reduction of embodied energy when compared to the assembly requirements of normal-weight concrete. For the same reason, using lightweight concrete also contributed 5.3 percent fewer overall emissions than normal-weight concrete—further accentuating this material’s utility in sustainable construction.1 While not completely quantifiable, it is also important to note a building’s resiliency when discussing sustainable building practices. If materials present initially sustainable metrics but need to be replaced or repaired often, due to their inability to withstand natural or manmade weathering, then they may not be the most ecologically conscious material to specify. Lightweight concrete not only resists chloride attack and premature cracking but also helps provide substantial resilience to seismic activity and other natural disasters. This means buildings made from lightweight concrete have a greater chance of withstanding cataclysmic events, as well as normal weathering without the need for extensive repairs and replacements. Accordingly, buildings made more resilient with lightweight concrete can mitigate the ecological impact of future repairs, contributing to the long-term sustainability of a building. Notes |

A five-story building completed in Salt Lake City provides an excellent example. The Utelite Corporation completed the concrete flooring assemblies in 2017 and produced a cost comparison report on the building. The report summarizes data for building designs with the following basic parameters: a design 133.4-mm (5.25-in.) thick lightweight concrete 1762 kg/cm3 (110 pcf) floors with a two-hour fire rating and a design for 165-mm (6.5-in.) thick normal-weight concrete 2323 kg/cm3 (145 pcf) floors which achieve the same two-hour fire rating. As assumed, the per m3 (cf) cost of lightweight concrete was greater than normal-weight concrete by 7.5 percent. Additionally, the lightweight concrete design required more shear studs, further increasing the cost.7

[4]

[4]However, lightweight concrete provided savings in other areas to produce a net cost which was 9.2 percent less than the normal-weight concrete design, which translates to over $435,000 saved. The greatest cost savings can be found in the footings. The use of lightweight concrete presented a 27 percent reduction in footing cost due to reduced structural load. Further, because lightweight concrete reduces the dead load due to its low density and thinner floor slab requirements, the steel framing cost was reduced by 10.5 percent. While the savings from these two areas greatly outweigh the increased material cost of the concrete and shear studs, it is important to note how the floor slabs required less labor to install, also providing enough savings to more than offset increased material cost.

Additionally, the study found the total floor weight for the lightweight concrete design was 18.3 percent lighter than normal-weight concrete, reducing the seismic mass and base shear by 23 and 21 percent, respectively. This contributed to additional savings in foundation costs.

To answer this question, lightweight concrete is more expensive than normal-weight concrete based on per cubic meter (cubic yard) costs alone. However, when the complete design of a building is considered, lightweight concrete drives economies that not only offset its higher initial cost but can lead to net savings in a building’s bottom line.

Heavy savings and benefits

Lightweight concrete can have comparable strengths and drying times as normal-weight concrete but with typically 25 to 35 percent of the weight. The reduced weight provides significant savings, as well as increased resilience to seismic activity. Further, the material can also provide longer spans and thinner slabs while satisfying requisite building safety codes. However, before choosing lightweight over normal-weight concrete, it is important for specifiers clearly know and communicate to the contractor all the details of the project, including if the required density is the plastic, estimated 28-day air dried, or the calculated equilibrium density as determined according to ASTM C567, Standard Test Method for Determining Density of Structural Lightweight Concrete, to ensure they choose the right material for the application.

If feasible, lightweight concrete’s long-term durability can help create more resilient and cost-effective buildings to satisfy owners. After more than a hundred years of designing low-rise, mid-rise, and high-rise buildings, many specifiers believe lightweight aggregate concrete to be the right choice for many jobs. According to Michael Corrin, PE, at Stanley D. Lindsey and Associates Ltd., “Recent trends for long floor spans have once again pushed lightweight concrete to the forefront as it allows the minimal depth of structure, yet still provides damping resistance to minimize vibration.” These benefits in conjunction with its ability to provide net savings to the bottom line makes lightweight concrete a dependable means to complete a project.

Notes

1 Consult IS032 Structural Lightweight Concrete, by Richard P. Bohan and John Ries, Portland Cement Association.

2 See Structural Lightweight Concrete on Fire Rated Steel Deck Assemblies: Higher Performance at Every Level, Expanded Shale, Clay and Slate Institute, https://www.escsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/4730.0-SLWC-on-Fire-Rated-Steel-Deck-Assemblies.pdf.

3 Read Cracking tendency of lightweight concrete, by B.E. Byard and A.K. Schindler, Highway Research Center, Auburn, Ala.

4 Read Long Wait for Lightweight, by B.A. Suprenant and W.R. Malisch, Concrete Construction.

5 Refer to Concrete Floor Drying Study for the Expanded Shale, Clay, and Slate Institute, by P.A. Craig, Expanded Shale, Clay, and Slate Institute.

6 Consult Concrete: Microstructure, Properties, and Materials, 3rd Edition, by P.K. Mehta and P.J.M. Monteiro, McGraw-Hill, Inc.

7 See Five Story Commercial Building Study, Utelite Corp, https://www.utelite.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Utelite-Study-Report-2022-01-26.pdf Accessed June 15, 2022.

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/LWC2_please-credit-the-Expanded-Shale-Clay-and-Slate-Institute.gif

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/1-13-2023-1-05-06-PM.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/second-table-cost-comparison-of-LWC-NWC.gif

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/LWC1_please-credit-the-Expanded-Shale-Clay-and-Slate-Institute-.gif

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/clearing-specifiers-misconceptions-about-lightweight-concrete/