Condensation: Why fenestration component selection matters

Improving the frame

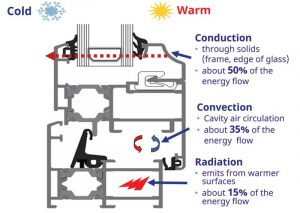

Eighty-five percent of the thermal bridging of windows occurs at the perimeter. Conduction through the frame and edge of glass is responsible for 50 percent of the energy flow, convection accounts for 35 percent, and radiation accounts for the remainder (Figure 1).

Improving the performance of aluminum frames typically starts with reducing the conductive heat flow by making a break in the continuous metal using a non-metal material. These are called thermal barriers and the wider the thermal barrier, the lower the thermal conduction. For polyamide (PA) thermal barriers, widths from 10-mm (0.4-in.) up to 100-mm (4-in.) are possible.

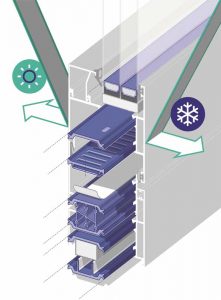

Once conduction is addressed, strategies to reduce convective heat transfer, such as adding legs or foam to the thermal barriers, can be introduced (Figure 2). These strategies stop convection currents by breaking up or filling large cavities formed in the extrusions. Additional performance can be gained by reducing the thermal conductivity of the polyamide (low lambda) or adding reflective surfaces to reduce radiative heat flow.

Used in this simulation study were (i) simple 13-mm (0.5-in.) wide PA thermal barriers, (ii) wider 25-mm (1-in.) PA thermal barriers, and (iii) 44-mm (1.75-in.) wide high-performance PA systems using various foam filling and complex geometries for convection mitigation.

Improving the edge of glass (EOG)

Historically, highly conductive aluminum box spacer has been used in insulating glass units (IGUs). If a spacer is not specified in project documents, aluminum box spacer is likely what will be delivered, since it is typically the least expensive option.

To reduce thermal conduction across the EOG, aluminum box spacer can be replaced with lower conductivity options generically called “warm-edge” spacer. While stainless-steel versions of the standard box spacer are considered warm-edge, those used in commercial applications tend to only deliver a 0.06 W/m2K (0.01 BTU/F.hr.sf) improvement in window assembly U-factor, whereas using lower conductivity warm-edge spacer delivers a 0.11 to 0.17 W/m2K (0.02 to 0.03 BTU/F.hr.sf) improvement.

Several lower conductivity warm-edge options are available, including the industry standard plastic hybrid stainless steel (PHSS) box spacer (Figure 2), which delivers the same thermal performance as non-metal spacer, with the benchmark durability of a metal box spacer. The engineered plastic bridging the top reduces heat flow across the cavity, while the low conductivity thin stainless steel wrapping the back and sides provides an excellent vapor and gas barrier, as well as an effective sealing surface. As an example of warm-edge performance, the PHSS spacer was used in the simulation study in comparison to a high-conductivity aluminum box spacer.