Compared with system 3A, which also used an aluminum spacer, but a smaller thermal barrier, 4A showed no major difference in extent of condensation, despite the higher thermal performance frame. This further indicates that spacer conductivity drives the extent of condensation once the frame conductivity is sufficiently reduced.

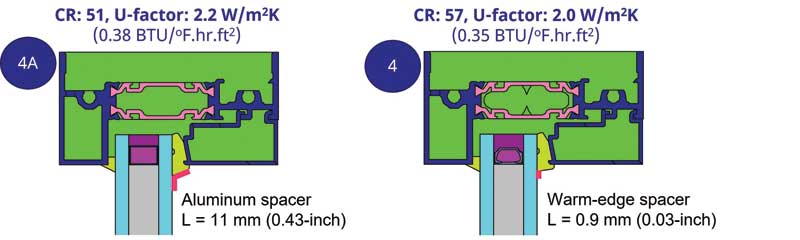

When comparing system 4A with 4 (Figure 9), where the only difference is spacer conductivity, the warm-edge spacer significantly reduced the extent of condensation.

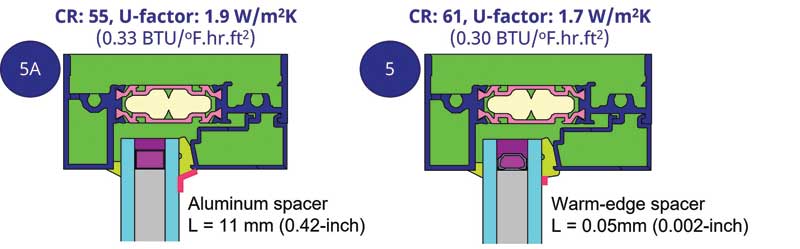

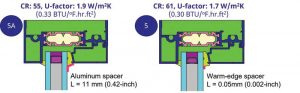

Systems 5A and 5 showed similar results as 4A and 4: (i) CR and U-factor improvements did not translate to less condensation at the given environmental conditions and (ii) incorporating a warm-edge spacer in system 5 made a significant improvement compared to 5A (Figure 10).

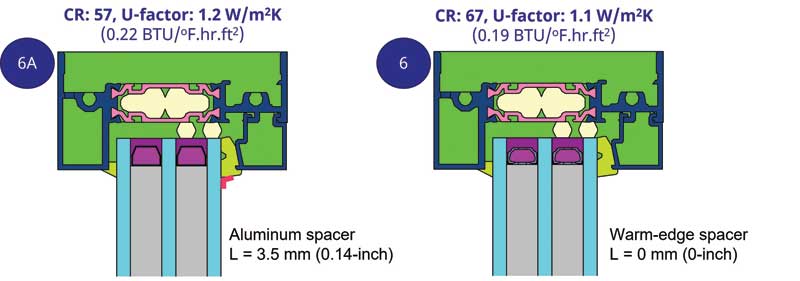

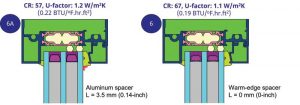

Systems 6A and 6 incorporate triple glazing, which reduces the condensation extent further (Figure 11). System 6, with the warm-edge spacer, had no condensation under any of the environmental conditions, yet system 6A with aluminum spacer still exhibits some condensation—because of the conductive spacer. To attempt to bring system 6 to a point of condensation, it was simulated at outside temperatures down to -62 C (-80 F). Even at this extreme condition, it did not experience condensation at 60 percent RH.

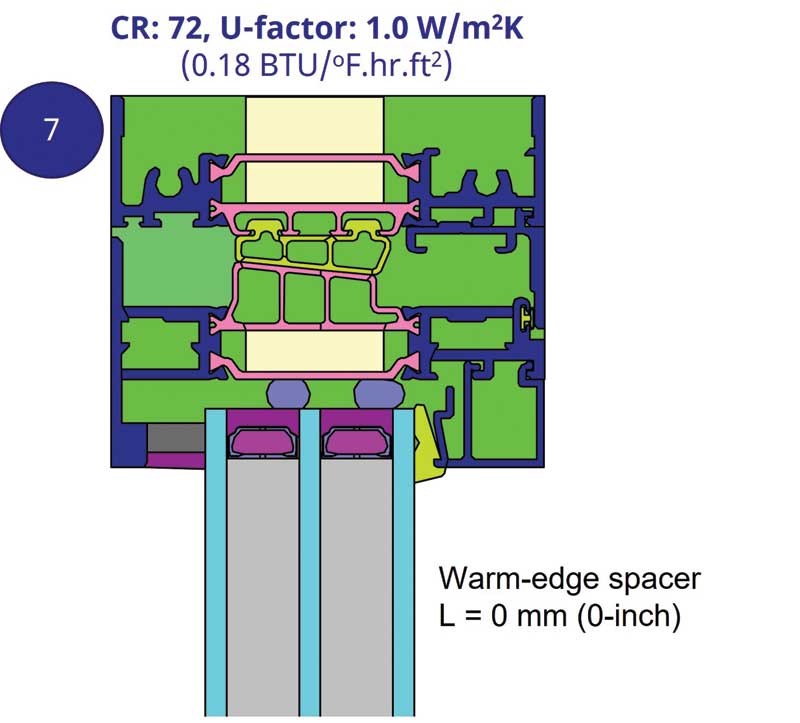

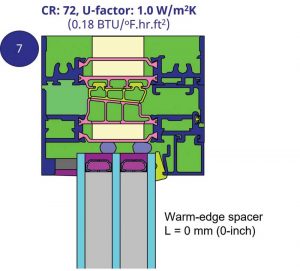

System 7 (Figure 12) with an even lower conductance frame, behaved like system 6. It was evaluated at further environmental extremes and did not experience condensation until an exterior temperature of -68 C (-90 F), a very unlikely condition.