Photography

A picture is worth a thousand words. It is often difficult to describe a deteriorated detail using text, but text illustrated with a photograph clearly describes the condition. Photography should be utilized extensively throughout the campus assessment. Not only will deteriorated conditions be documented, but a carefully planned photographic survey will also allow the architect or engineer, now back in the office, to evaluate found conditions. Overall photographs of each building elevation, accompanied by close-ups of details, can

be transposed or keyed to building drawings.

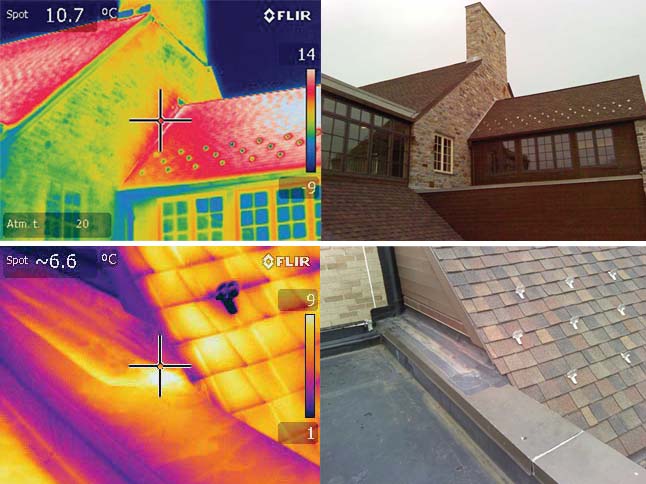

In order to aid in diagnosing pesky—and sometimes mysterious—leaks, infrared or thermal photography is often beneficial. While this type of photographic documentation ‘sees’ heat or temperature differentials and not moisture, the presence of water can be confirmed with a moisture meter or an invasive probe. Thermal photographs also reveal missing or insufficient insulation, discern air leakage at dissimilar component interfaces such as window-to-wall intersections, and can even detect embedded pipes and electrical wires.

Existing record consultation

If historical records—such as drawings and specifications, roof warranty documents, or facilities department work orders—are available, their information can be invaluable. This documentation may assist the architect or engineer in determining the remaining useful life of a roof or window, or allow the owner to implement immediate roof repairs covered by a manufacturer’s warranty.

The designs for repairs by previous professionals are also useful in determining component lifespan and understanding built conditions. If these are available, they can be reviewed and considered as part of the assessment.

Original drawings and details are extremely beneficial. If the design professional is fortunate enough to have access to the original building documents, they can be used to illustrate and map deteriorated conditions, more clearly understand deterioration trends or common issues, and provide context for area takeoffs, component counts, and finally cost-estimating.

Interviews with facilities staff

The people who best know the conditions of a building are those who respond on a daily basis to maintenance and repair demands: the facilities team. Where written documentation falls short, staff members can fill in details of recent repairs and known issues that may not have been committed to the paper archive or may benefit from in-person elaboration. The people who deal with occupant complaints about drafty windows, a crumbling entry plaza, doors that do not close properly, or roof leaks are suited to provide up-close and to-the-minute accounts of challenges that should be included in building envelope maintenance planning. Without their inside information, the assessment could fall short of documenting the myriad small repair needs that can easily be overlooked in the scheme of major rehabilitation concerns at a large institution.

Facilities staff can also provide insight into project funding and the accurate allocation of resources to areas slated for repair. By helping pinpoint the nature and extent of problems, the maintenance team can guide the architect or engineer in creating project cost estimates better in line with the true nature of the issue.

In addition to providing a day-to-day picture of current maintenance challenges, interviews with facilities staff can also reveal the priorities of trustees, alumni, and other stakeholders, which might affect the approach to building envelope rehabilitation. For example, nostalgic university alumni might wish to maintain buildings exactly as they remembered them—not just in overall appearance, but in every detail. Even when component replacement could recreate the original building element, it is useful to know going into the discussion key decision-makers are adamantly opposed to removal of any existing material, no matter how deteriorated. Time and resources wasted researching in-kind replacement could then be saved, with the conversation firmly rooted in options for conservation.

Contrarily, another institution might find the push from stakeholders is toward sustainability and energy efficiency at the expense of historic preservation. In such cases, replacement of a component in favor of a better-performing one would tend to be the preferred solution.

Without conferring with the facilities management team, the architect or engineer developing the building envelope assessment might miss these crucial pieces of information regarding the institution’s stance on exterior rehabilitation.