Connecting it all: Role of joints as a primary component

For masonry wall assemblies, mortar joints also play a key role in managing moisture. Although properly filled mortar joints keep out bulk water from precipitation, as a porous material, they do admit moisture through capillary action. Masonry assemblies handle moisture in different ways depending on wall type. In multi-wythe masonry with solid filled collar joints (vertical joints between wythes), the wall acts like a sponge that absorbs moisture but is usually too thick for the moisture to reach interior surfaces. In dry weather, the moisture evaporates, as mortar is vapor permeable (capable of allowing gaseous water to pass through it). This system is referred to as a “mass wall,” the most common type of masonry assembly for thousands of years.

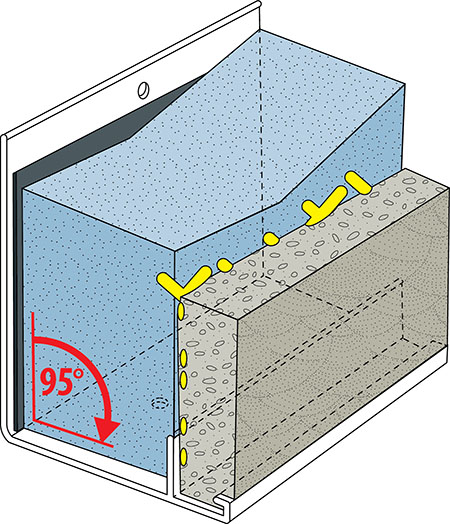

Developed in the 20th century, the cavity wall system operates like a rainscreen. It consists of one wythe of masonry separated from the back-up by an air cavity. Moisture that infiltrates the joints by capillary action drains inside the cavity to weep holes at the base of the wall, at relieving angles, and at window and door lintels. It can also evaporate from ventilation provided through the weep holes. Given the absence of a bonded mortar collar joint or header blocks to tie the face masonry to the back-up, regularly spaced wall ties are critical for structural securement.

For both masonry wall systems, the reason porous mortar is used is because brick and stone are also porous. This means some moisture intrusion is inevitable, even if joints are watertight. Therefore, joint mortar that is more porous and vapor-permeable than the masonry itself is used to facilitate breathability. Inappropriate, non-breathable joint materials could trap moisture and cause the adjacent masonry to spall from freeze/thaw damage or from corrosion of the underlying metal, or it could cause joints themselves to fail if the substrates become compromised.

There are masonry assemblies where watertight joints are appropriate, including copings at parapet walls (the portion of facades which extends above the roof). This typically involves installing sealant caulking at sky-facing transverse joints between masonry coping blocks, sometimes complemented with T-shaped lead joint covers to protect the sealant from UV degradation. An alternative approach is placing sheet metal copings over the top of the parapet and joining them with sheet metal splice plates set in beads of caulking. As the most exposed part of the wall, copings play a key role in avoiding freeze/thaw damage to masonry or corrosion of its underlying metal reinforcement, which can generate safety hazards if parts become cracked, spalled, loose, or displaced. Preventing water infiltration at copings also helps keep moisture from working its way under roofing.

Some modern masonry wall claddings use sealant or foam gaskets in lieu of mortar joints, such as stone panel systems supported by metal anchor straps secured to structural backup. These systems often employ a less porous, less moisture-absorbent stone such as granite, but typically still provide a means for infiltrated incidental moisture to weep out from an air cavity behind the panels.

Fenestration systems, including windows, curtain walls, storefronts, and doors can involve much more complex joint assemblies. Where window and door frames meet opaque facade systems, joints are typically sealed with caulking at both the exterior and interior. This is to fully protect against air and water leaks, since fenestration openings are among the weakest points in a building enclosure, as the gaps are otherwise only filled with intermittent shims and anchors. The flexible caulking also allows for inevitable movement, especially given that wind loads applied to fenestration can cause deflection, which is compounded by the material differences between adjacent systems (e.g. masonry walls with metal or wood windows).