Connecting it all: Role of joints as a primary component

Joints: Form and history

Technical knowledge of joint design is not isolated to advancements made in the past decade or even the past century; it is an inheritance born out of millennia of trial and error, as builders learned the advantages of different materials and configurations. A review of structures dating to antiquity reveals the trajectory of joint evolution. In the case of mortar, ancient Egyptians combined clay with mud and sand to bind the stone blocks of the early pyramids thousands of years ago. For the Great Pyramid of Giza, mortar consisting of gypsum and rubble was used to fill gaps between roughly cut stones that formed the core. However, the outer cladding used no mortar, but it contained stones cut so precisely that it is said not even a sheet of paper could pass through the open joints. Without mortar delineating the borders of each block, the uninterrupted sloped walls became more visually monolithic, reinforcing the overall pyramidal geometry, and emphasizing the monumental role of the structure. Ancient Greeks similarly used dry-stacked stone to erect temples such as the Erechtheion, in the fifth century BC. Their technique involved laying stones on a tight, compact bed of sand, and once again, the thin joints aided in the expression of Herculean form.

Jumping from antiquity to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there are numerous examples of masonry buildings that employed ultra-thin lime mortar joints to again reinforce the monolithic appearance of buildings. An example that did not use mortar is the Morgan Library in Manhattan, designed by Charles McKim. The stone façade blocks are separated only by a layer of sheet lead, approximately 1/64 inch thick, allowing the joints to visually render as nearly two-dimensional lines along the face of the blocks, providing a subtle and highly controlled joint expression.

Joints can also be used to emphasize directionality of form. Architect Frank Lloyd Wright, known for his distinct Prairie Style, used masonry in tandem with mortar joints to further emphasize horizontality and connection to the open planar landscape of the Midwestern U.S. At Robie House in Chicago, the long masonry facade and site walls contain horizontal bed joints between bricks that are raked back to create shadow lines. In contrast, the vertical head joints are flush with adjacent brick and colored to match it to further deemphasize verticality. The use of deep raked joints reinforced Wright’s architectural philosophy, but different mortar tooling profiles have performance implications. Raked and struck joints do not shed water from facades, as well as V-shaped and especially concave shaped profiles, which also better seal against the outer face of the masonry. Squeezed and beaded joints involve building up mortar beyond the surface of the masonry to create a more rustic appearance, but can also be problematic as they create exposed ledges where water can sit and facilitate premature joint failure from freeze/thaw damage.

In contrast to masonry assemblies, glass enclosures offer a fundamentally different visual impact. Typically used to express a lightweight, often minimalist design philosophy, glazed walls can promote varying degrees of exhibitionism. Apple Fifth Avenue, designed by Bohlin Cywinski Jackson, features an all-glass cube entrance. The glass panels invite outsiders to view the Apple logo that hangs from the top of the glass cube, and to look down into the underground retail space. Rather than opaque metal mullions, the glass is supported by a interior glass fins that meet the panels at the joints, connected only by clear structural silicone sealant, further emphasizing transparency.

Maximizing glazing in facades came to fruition with Mid-Century Modernism. Architects such as Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe used glass curtain wall systems in numerous high-rise buildings. While more recent constructions can trace their material lineage back to buildings such as Mies’ Seagram Building, opened in 1958, they inherently stand in contrast in the way they employ glazing joints. Whereas Miesian structures contained large sheets of glass separated by metal mullions and non-load-bearing I-beams, with concealed gasket joints, Apple Fifth Avenue uses barely any metal at all, but rather employs technological advancements in joint materials to achieve an aesthetic goal.

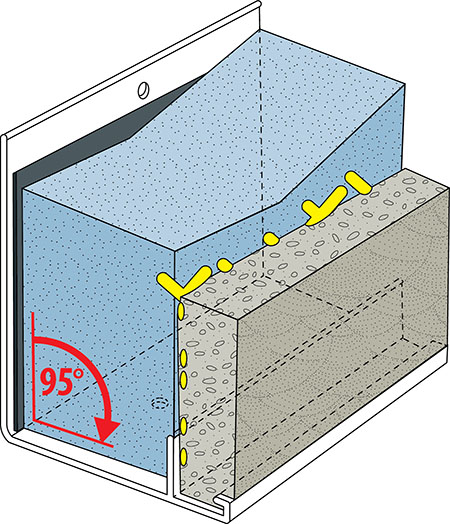

For some glass facades, joints can become a means of introducing planar shifts. Peter Zumthor’s Kunsthaus Bregenz, an art gallery building located in Austria, utilizes translucent glass panels mounted to steel clips in a rainscreen cladding system. The panels are angled so each one overlaps adjacent panels in a way that echoes the textures of historic open joint shingle roof systems, such as slate and terra cotta, but using glass further plays with light and shadow. Not only do the sloped lapped panels facilitate water drainage, but they also enrich the otherwise flat facade with creative three-dimensional manipulation of repeating joints.