Construction and silicosis: the new rule

What is silicosis?

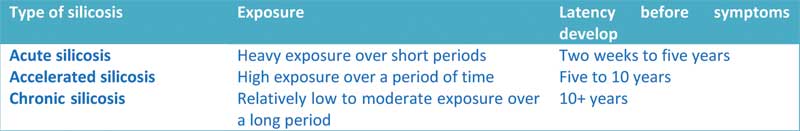

Silicosis is associated with inflammation and scarring of the upper lobes of the lungs in the form of lesions. While symptoms related to asbestos may take between 10 and 50 years to manifest, the effects of silicosis can start within a short period, as seen in the Hawks Nest Disaster (Figure 3).1 Individual susceptibility is based on factors such as amount of dust, its size, RPE worn, the individual’s overall health status, and whether the person is a smoker.

In acute form (i.e. short-term, severe, or sudden), the symptoms are typically bluish skin, breath shortness, coughing, and fever. It is not uncommon for this to be misdiagnosed as pulmonary oedema (i.e. water in the lungs), pneumonia, or tuberculosis. Symptoms can continue to develop even after exposure has stopped. Other conditions can also occur, such as bronchitis, lung cancer, or arthritis.

So how can construction professionals work safely without being harmed? If the threat of exposure to RCS cannot be eliminated altogether, then there are a few control measures that may work in keeping dust to relatively safe levels. To ensure compliance, the local safe systems of work need to be followed. Generally, they are based on the principles of occupational hygiene: assess, control, and review.

Assessing and controlling the risks

High dust levels at the jobsite are caused by one or more of the following:

- task—high-energy tools can produce a lot of dust in a very short period;

- work area—the more enclosed a space, the more the dust builds up (one should not assume dust levels will be low when working outside);

- time—the longer the work takes, the more dust there will be; and

- frequency—regularly doing the same work day after day increases the risks of exposure.

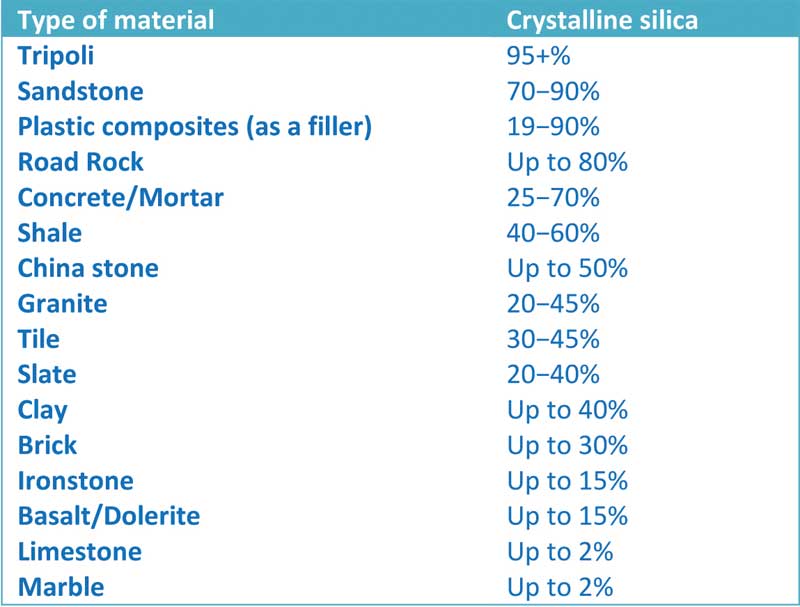

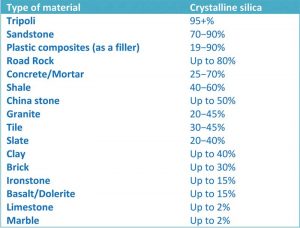

For specific activities where RCS could become airborne, separating the workers and the airborne materials can be a successful solution. In some cases, the means can be as simple as dousing the dust source with a water stream and standing upwind. Where possible, it is also important to specify materials that have less silica content or do not produce large volumes of dust.

Stopping or reducing the dust before work starts is also crucial for controlling the risks, and is consistent with the new silica rule. This might mean different materials (e.g. the right size of building materials reduces cutting or preparation), less-powerful tools, or other work methods.

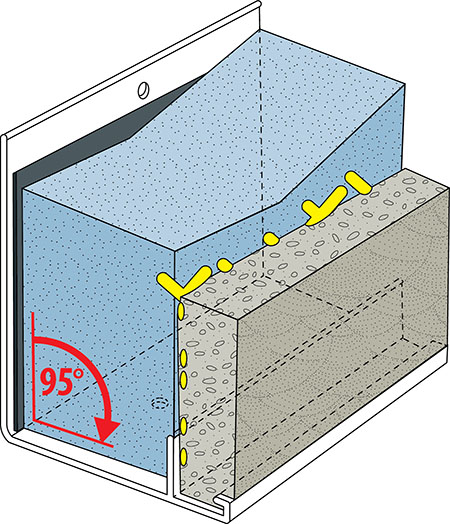

Regardless, the most important action is to stop the dust getting into the air, and more critically into the breathing zone of the workers. There are two main ways of doing this effectively: water and on-tool extraction.

Water damps down dust clouds, but to be effective, this needs to be in a fine mist or deluge form at a steady volume rate. Simply dampening material beforehand may not be as effective.

On-tool extraction removes dust as it is being produced. This type of local exhaust ventilation (LEV) fits directly onto the plant, tools, and equipment. The “system” consists of several individual parts—the tool, capturing hood, extraction unit, and tubing. It important to use an extraction unit to the correct specification (i.e. H [high], M [medium], or L [low] class of filter unit), and without sweeping. An industrial vacuum cleaner with a high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter should be employed.