Controlling moisture balance with watertight vapor-open assemblies

Vapor barriers and vapor retarders defined

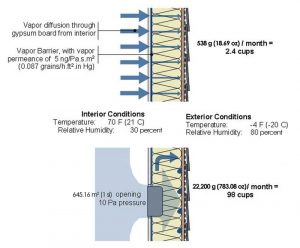

While the goal is to limit the air flow through walls, the air that does make it into the walls (from the conditioned or unconditioned side) may leave condensation behind when it goes from warm to cold. Making a wall or building as airtight as possible makes sense at first. However, the wall assembly should, preferably, be water vapor permeable to allow incidental moisture to escape or diffuse, instead of being trapped and forced into the wall materials. This is not always as easy as it sounds.

A vapor retarder, according to the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE), is designed and installed in an assembly to retard the movement of water by vapor diffusion. There are several classes of vapor retarders from which to choose. The International Building Code (IBC) uses ASTM E96 Method A to categorize materials as vapor retarders. For example, according to the 2018 IBC, the Vapor Retarder Classifications are:

• Class I: 0.1 perm or less;

• Class II: 1.0 perm or less and greater than 0.1 perm; and

• Class III: 10 perm or less and greater than 1.0 perm.

Colloquially, what one typically refers to as a vapor barrier is a Class I vapor retarder. To be classified as vapor permeable, a membrane needs to have a permeance of 10 perms or greater, per the ASHRAE Journal. However, the higher the perms, the better vapor can diffuse through.

When designing a well-performing wall assembly, specifiers should consider:

• using a water-resistive barrier to keep bulk water out of the wall;

• using an air barrier to prevent air movement through the wall, which could cause condensation; and

• using vapor control appropriate for the type of wall and climate zone.

In many assemblies, vapor barriers can be placed on the warm side of the insulation without being sealed airtight if there is an uninterrupted air barrier somewhere else in the wall and ceiling assemblies. However, the best practice is to fully tape and seal the vapor barrier so it is airtight. The reason for this is simple: diffusion of moisture vapor is slow, relative to much quicker air movement, which carries more moisture vapor quicker. However, a single material may perform more than one control function. For example, some materials may act as both the air- and the water-resistive barrier.

Designing a building to be as airtight as possible is an important first step when determining which barriers to use; the more airtight the building, the fewer vapor issues will crop up. Contrary to common belief, a building cannot be “too airtight,” which is not to say a building does not need air exchanges. For proper air exchange, one should have a correctly sized and calibrated HVAC system.

A design can eliminate the risk of mold and rot by also allowing existing moisture to escape. The vapor permeability and airtightness of a good air and water-resistive barrier makes it ideal for building and helping to maintaining healthy and comfortable interiors while letting moisture out and improving energy efficiency.

It is expensive to install moisture control measures after a building is complete. It is much cheaper to do correctly at the time of initial construction. A building must emphasize air and vapor control as part of its design, rather than attempting a retrofit, so it will be much more secure against mold, mildew, and other problems. This also ensures there will be fewer issues and expenses down the road.