by Katie McKain, ASLA, MLA, MUD

Conventional stormwater systems treat precipitation as a waste product, directing it into storm drains and pipes and pouring it into receiving waters. These traditional development systems also cause undesirable effects to the landscape, such as reducing the water table and its overall quality, as well as leading to erosion, sedimentation, and flooding issues.1

As the impervious surfaces characterizing urban sprawl—roads, parking lots, driveways, and roofs—replace meadows and forests, rain can no longer seep into the ground to replenish aquifers. This reduces the groundwater recharge serving as a natural hydrologic process where surface water infiltrates downward into groundwater to maintain the water table level.

The infiltration process naturally filters runoff through vegetation and soils. Not only do conventional systems prevent groundwater recharge, but they also cause significant stress to waterways and affect water quality. When the natural process does not happen, runoff spreads over impervious surfaces and gathers pollutants that wash into lakes, rivers, and streams, contaminating them.

There is also a negative financial connotation as building impervious surfaces and concrete curb and gutter systems are expensive. Curbs and gutters, and the associated underground storm sewers, frequently cost as much as $36 per 0.3 m (1 ft), which is roughly twice the cost of a grass swale. When curbs and gutters can be eliminated, the cost savings and positive effects on the environment can be considerable.

What is low-impact development?

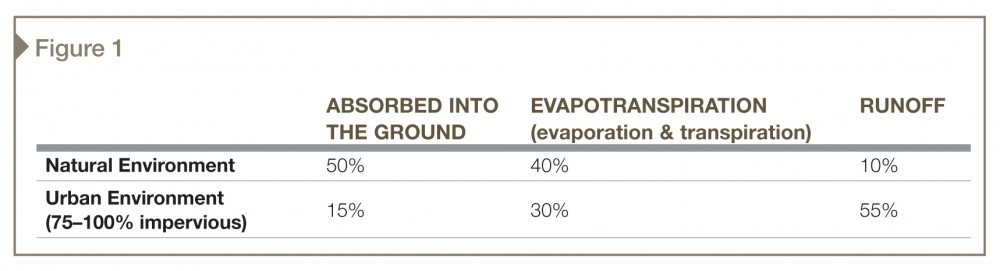

As shown in Figure 1, the ultimate destination of water after rainfall is divided into three categories:

- absorbed into the ground;

- evapotranspiration; and

- runoff.

There is a dramatic difference between water movement on natural areas versus urban impervious environments.

The negative effects associated with unnaturally high runoff volumes from conventional practices have initiated the emergence of low-impact development (LID). The Low Impact Development Center is a non-profit organization in Beltsville, Maryland, dedicated to the promotion of this strategy, which it defines as:

a new, comprehensive land planning and engineering design approach with a goal of maintaining and enhancing the pre-development hydrologic regime of urban and developing watersheds.2

LID promotes integration of stormwater management into site and building designs, controlling stormwater at the source before it collects and deposits harmful pollutants. Another crucial component involves minimizing impervious areas and ensuring buffer zones between them. This allows infiltration and daylighting of runoff to the surface, controlling stormwater at the source. (In this context, ‘daylighting’ is used to describe an underground pipe conveying water that ends at the surface, so water rushes out of the pipe onto gravel or grass and the pipe is no longer underground.)

Advantages to using low-impact development

Some of the numerous benefits to designing with the LID model are discussed below.

Improved water quality

Many best management practices (BMPs) involve bioretention—a process using the chemical, biological, and physical properties of plants, microbes, and soils to improve water quality. Hyperaccumulators are unique plants with natural abilities to degrade, bioaccumulate, or render harmless contaminants in soil, water, and air.

There are many species of hyperaccumulators, including:

- barley (i.e. hordeum vulgare);

- water lettuce (i.e. pistia stratiotes); and

- Indian mustard (i.e. brassica juncea).

These common types respectively counter aluminum, mercury, and lead. Bioretention techniques include adsorption, absorption, volatilization, decomposition, phytoremediation, and bioremediation.

Increased groundwater recharge

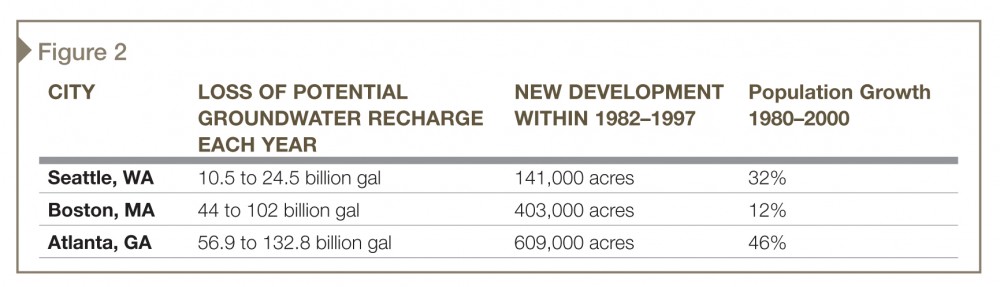

General water infiltration is important for groundwater recharge (i.e. replenishing the water table). Unsatisfactory groundwater recharge is becoming a serious concern as cities continue to develop land with impervious surfaces (Figure 2).

As the statistics are directly proportional, it is not surprising Atlanta earned the ‘top’ ranking for both loss of potential groundwater recharge and acres of new development. These extremely high numbers should also take the population increase into account, but Seattle managed much lower numbers across the board despite having a relatively high population increase. (While this is perhaps due to the West Coast city’s advances in stormwater management, it should also be noted Atlanta sees an average of 304 mm [12 in.] more annual rain than Seattle.)

When water is sent to a treatment facility instead of infiltrating to the groundwater, it is often taken far from its place of origin, depleting waterways of their natural processes. The sewer system not only diminishes groundwater supplies, but also causes significant stress to the waterways and affecting water quality.

When contaminated water runs off into rivers and lakes, it poisons the water and aquatic life; further, most of it evaporates without making it into the groundwater recharge cycle. Some runoff actually leaks into sewage systems of fading infrastructure. When there is not ample groundwater recharge, the water table is lowered and negatively affects all facets of nature, including the drinking water supply. BMPs aim to promote infiltration to satisfy the necessary groundwater recharge.

Reduced erosion, flooding, sedimentation, and water temperature

LID practices reduce stormwater rate, volume, and temperature. By lowering volume and rates of runoff, phenomenon occurrences (e.g. erosion, flooding, and sedimentation) also decrease. Pollutants increase the faster and farther runoff travels on impervious surfaces, with more speed causing runoff to warm up before depositing into lakes and streams and adversely affecting aquatic life.

Disconnecting impervious surfaces and adding permeable surfaces are the best ways to decrease flow rate and volume of runoff. Aesthetically, providing green space and visual attractions in a usually less appealing area, such as a parking lot, is always a benefit to consider.

Designing with LID principles and incorporating BMPs into site designs are responsible and affordable ways of incorporating the land and its natural processes into development. The U.S Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines a BMP as a:

technique, measure, or structural control that is used for a given set of conditions to manage the quantity and improve the quality of stormwater runoff in the most cost-effective manner.

Common types of stormwater BMPs

There are many types of stormwater BMPs to consider for a design. A site analysis should be performed to note the area’s size and the amount of water that must be accommodated. Each BMP has unique pros and cons and is site-dependent. In many cases, BMPs are cheaper alternatives to curb and gutter systems.

Bioretention swales, bioswales, vegetated swales

Bioretention swales are long, narrow landscaped channels that cleanse runoff using bioretention techniques, as well as infiltrate water and act as a conveyance system.

Phytoremediation is the process enabling plants to naturally remove toxic metals from the water. Typically, this process is not immediate, so the swale should be designed to hold water for more than 48 hours. A gentle slope is used within a swale to move water through it slowly enough for the plants to respond. Vegetation in the swale must be flood-tolerant, erosion-resistant, close-growing, and efficient at removing pollution. This is the case for plants able to extract high concentrations of metal from the soil into their roots, also called hyperaccumulators.

Swales can be wet, riparian areas, or they can be dry areas only wet during large storms. Typically, irrigating a swale is not a good practice except for the establishment of vegetation—a period that typically takes two to three years. Grassy swales, similar to vegetated ones in their design and activity, are landscaped solely with a mixture of grasses. The major difference is maintenance and form, as the grasses can be left to grow tall, be mowed constantly (e.g. buffer strips adjacent to streets), or mowed occasionally, depending on aesthetic and stormwater-filtering requirements.

Swales are inexpensive compared to traditional curb and gutter techniques. Although maintenance is an increased concern, a swale is still less costly and provides more benefits.

Rain gardens, infiltration basins, planter boxes

Rain gardens are meant to be a short-term bioretention area that fluctuates between wet and dry conditions depending on the space. Collectors of water runoff, these rain gardens typically consist of grasses adaptable to wet or dry conditions, but can also contain flowering plants and hyperaccumulator plants. The main function of a rain garden is to allow the stormwater to infiltrate into the ground and recharge the stormwater reserve, but they also allow for plant- and soil-filtering functions to improve water quality. These gardens are situated close to the runoff source; unlike swales, rain gardens do not convey the water to a specific place—they promote infiltration in a smaller contained area.

Rain gardens must be positioned close to the source, and the water table must be at least 1.5 m (5 ft) below the basin at its peak. This is because if runoff into a rain garden travels a long way and picks up excess pollutants and sediments, infiltration may not cleanse it enough. As a result, the ground water could be contaminated or the system clogged. Additionally, the type of soil needed to accommodate proper infiltration of 12.7 to 76.2 mm (1/2 to 3 in.) per hour is an extremely important design pre-treatment. The soil should have no greater than 20 percent clay content, and less than 40 percent silt/clay content.

Although vegetation within infiltration basins is encouraged for optimal filtering, basins can also have layers of sand and rocks in a type of soakage trench, without vegetation. Infiltration basins are cost-effective practices because little infrastructure is needed when constructing them.

Another way to collect stormwater is to use a rainbarrel or cistern to harvest rain water, commonly from a roof downspout. By collecting water, and repurposing it, runoff is prevented. Water collected in such barrels is then commonly re-used to irrigate lawns or gardens and can be used in other non-potable uses such as flushing toilets. However, it should be noted, due to water laws and restrictions, it is illegal to harvest rainwater in some areas of the United States.

Constructed wetlands: Detention ponds/retention ponds

Constructed ponds and wetlands are designed by engineers to prevent runoff by holding stormwater. Detention ponds are larger, less-particular versions of infiltration basins. They typically have a fore bay to allow particles and pollutants to settle and be treated; this prevents them from clogging the entire pond. Two important pieces of designing ponds include the removal of sediment buildup over time, as well as the simultaneous growth of hyperaccumulator plants that naturally filter water.

Typically, fore bays are a concrete surface, which allows for maintenance and removal of sediment buildup, but not vegetation growth. To plan around this problem a structured surface able to grow vegetation, such as a void-structured concrete, should be used. This material is similar to a concrete slab in structure, but has spaces large enough for hyperaccumulator vegetation to grow through. The vegetation’s roots are protected within the concrete cavity allowing for maintenance and removal of sediment as needed without distrubing the vegetation significantly.

Generally, detention basins can be used with almost all soils. While detention ponds can remain wet or sometimes dry up, retention ponds are typically deeper and always wet as well as retain stormwater for longer periods.

Green roofs

A green or vegetated roof consists of a waterproofing assembly, lightweight soil, and plants adapted to survive the area’s climate. An efficient BMP and prevention technique, vegetated roofs intercept rainwater directly at the source, preventing most of the water from becoming runoff. Since the rain is used by the vegetation, a major advantage to a green roof is its ability to decrease the volume of runoff, thus mitigating flow rates, flooding, erosion, and sedimentation.

Green roofs promote infiltration for the advantage of the vegetation on the roof, but not the water table. Additionally, green roofs provide wildlife habitat and attract birds. These assemblies also provide energy-saving benefits to the building, including increased insulation on the roof, mitigating building and roof temperatures, and possibly doubling the roof’s lifespan since it is protected from harsh weather.

There are two types of green roofs: intensive and extensive. The first type promotes human interaction where people are encouraged to use and interact with plant life amongst paths and gathering areas, these roofs can usually carry heavier loads and deeper soil. Conversely, extensive green roofs contain only vegetation over the entire roof with little human interaction. A green roof is a relatively high-cost BMP initially, but has energy-saving returns that are worthwhile in the long run.

Tree plantings

One of the most underused BMPs, tree plantings are effective at mitigating stormwater in urban settings due to their ability to absorb large amounts of water while needing little surface area. Trees provide shade and habitat, which helps reduce the urban heat island effect.

Trees are also an important factor in cleansing and filtering the air. The branches and leaves of trees help to soften rainfall speed, reducing both stormwater flow rates and erosion. Trees also help aid the view shed, breakup the impervious landscape, provide small but essential green spaces linking walkways and trails, and reduce the visual dominance of cars.

The success of tree plants, especially in urban settings, is largely determined by the species chosen and the size of the planting area, in addition to meeting its watering requirements. Species selection should be based on location, but an appropriately sized tree-well with plenty of soil volume makes the difference in how well it survives. Although there is a need to pave over tree roots in urban settings, leaving as much exposed to natural water as possible is the best plan; if paving is necessary, use permeable paving so water and oxygen can still get to the tree roots. Pouring concrete around a street tree of any variety guarantees stunted growth and little canopy.

Permeable paving

Arguably the most efficient BMP due to its practicality, permeable paving has been revolutionizing the green industry for years. Paved surfaces are a necessity in the built environment, and replacing traditional impervious concrete and asphalt with permeable materials is one of the easiest, effective, and cost-efficient methods of preventing runoff.

Permeable paving allows for water to percolate through cracks in the pavement and infiltrate directly to the soil, preventing runoff from ever occurring. Infiltration not only prevents runoff, but also replenishes the water table and allows for natural soil filtration to improve water quality. Incorporating stormwater treatment into parking areas and landscaped zones reduces required detention volume onsite. This allows for an increase in building area and the potential for further profitability for an LID-educated developer.

Permeable pavements also provide a reduction in the heat island effect, which is especially valuable in urban areas typically paved in dark colors and absorb light. Since permeable pavement allows for water infiltration, it also helps increase water quality using the soil as a filtering medium. There are many types of permeable pavements available with advantages and disadvantages, depending on the desired use and location.

Types of permeable pavement

Different types of permeable pavement can be used for various installations. Some examples are included below.

Void-structured concrete: grass- or stone-filled, or concealed with vegetation

Designed to combine the strength of traditional concrete with aesthetically pleasing vegetation, void-structured concrete is cast-in-place and contains a grid series of spaces that allow the system to be pervious in nature.

These voids can be filled with various porous materials such as vegetation or no-fines stone, or the entire system can be seeded over to completely conceal it, making it ideal for emergency access applications seeking to hide the eyesore of a road. Typically, void-structured concrete is used for fire and emergency access, military applications, parking lots, detention pond fore bays, and general stormwater management with heavy load requirements.

The typical lifecycle of the material is more than 15 years. Its benefits include:

- high load-bearing capacity (suitable for heavy traffic);

- high infiltration rates;

- low maintenance costs;

- freeze-thaw cycle resistance;

- ability to be effective with saturated sub-base;

- green space addition; and

- moderate installation costs.

Some challenges associated with void structured concrete are:

- not Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)-compliant;

- in pedestrian zones there is a need to incorporate bands of traditional concrete for ease of movability with all footwear; and

- surrounding grass needs to be properly maintained.

Permeable interlocking concrete pavement

Available in various shapes, sizes, and colors, permeable interlocking concrete pavers (PICPs) are designed to either let water infiltrate within voids in the unit itself, the space around them, or both. PICP is ideal for light traffic where intricate and aesthetically pleasing designs are desired. Often these systems are used for pedestrian walkways and garden paths.

The longevity of PICP is moderate, spanning seven to 15 years. PICP benefits include:

- high infiltration rates;

- various patterns and colors;

- can be ADA-compliant; and

- ease of maintenance if integrity of paver fails or if utilities underneath need to be reached.

Some challenging aspects of PICP are:

- system has a low load-bearing capacity (not suitable for heavy traffic applications);

- pavers are susceptible to movement and damage in freeze-thaw climates;

- high installation costs as a deep sub-base for optimal performance is required; and

- high maintenance costs.

Plastic grid systems reinforced with grass or gravel

Reinforced systems are most commonly seen as plastic ring systems. They are designed to provide vehicle stability for grassed or gravel surfaces without the visual eyesore of the plastic rings showing. This system is best used for short-term pedestrian and light vehicular traffic and is often seen on trails and for emergency access. Its lifecycle is typically less than seven years.

Benefits include:

- high infiltration rates;

- adds green space; and

- lightweight plastic is easy and cost-effective to install.

Challenges include:

- low load-bearing capacity (not suitable for heavy traffic applications);

- system commonly fails in saturated soils;

- susceptible to movement and damage in freeze-thaw climates;

- high maintenance costs as the system settles fast and plastic rings are commonly visible;

- not ADA-compliant; and

- grass needs to be properly maintained.

Gravel and crusher fines

Crushed rock type gravel and crusher fines, typically last less than seven years. Crusher fines can use a glue to help hold them together, reducing the infiltration rates. Due to their natural properties, they are commonly employed in park and trail settings without heavy slopes. Similar to some of the other materials discussed, they typically have high infiltration rates and low installation costs, along with the ability to withstand freeze-thaw cycles.

The system is not suitable for heavy traffic applications due to its low load-bearing capacity. It also commonly fails in saturated soils because the system is not stabilized well. Further, gravel and crusher fines are not appropriate for use on a slope because they develop ruts in heavy storms, resulting in high maintenance costs.

Pervious concrete and pervious asphalt

An alternative to their traditional counterparts, the pervious versions of concrete and asphalt employ larger aggregates in the mix. The result creates voids in the pavement that allow water to pass through to enter a temporary detention area and ultimately infiltrate to the ground. These products are different, but their advantages and disadvantages are similar.

Location is key to the performance of these systems. Typically, pervious concrete and asphalt perform the best in areas where available sediment is low, traffic volume is low, and maintenance can be regular and intensive. The lifecycle is typically seven to 15 years.

Benefits include:

- high load-bearing capacity (suitable for heavy traffic);

- moderate infiltration rates;

- aesthetic design options;

- ADA-compliant; and

- moderate installation cost.

Some challenges associated with pervious concrete and asphalt include:

- reduction in pavement surface (surface raveling is common where aggregate is dislodged or damaged);

- high maintenance costs as the system needs the quarterly use of an intensive vacuum sweeper to pull out sediment, and special winter maintenance for snow and ice conditions;

- reduction in porosity (clogging is the largest concern—even when regularly vacuumed, a clogged system cannot function and water ponds on the surface); and

- it can be susceptible to damage in freeze-thaw climates if system freezes with water in it.

With the cost of permeable pavements being fairly similar to conventional methods, it seems permeable pavement could replace nearly all impervious surfaces, but there are certainly exceptions to this idea. It is not recommended to use permeable pavements in areas where heavy pollution, leaks, or chemical spills could occur. While small oil drips from parked cars is considered acceptable for the soil to handle, a large chemical spill or heavy agricultural use would put soil and the water table in danger of being directly polluted.

It is also not recommended to use permeable pavement in areas where heavy sedimentation can occur—this could clog the system faster than it is designed to handle and could result in heavy maintenance costs.

Additionally, care should be taken to design for ADA-compliant access as wheelchairs and those who use walkers as an aid typically prefer the steady, smooth surface of traditional impervious surfaces. Some tracked vehicles may also be better handled on traditional surfaces to limit wear and tear.

Conclusion

Now commonly used for residential driveways, military applications, offices buildings, government buildings, and even grocery stores, permeable paving is emerging everywhere. LID stormwater management methods, with a focus on handling stormwater at the source, will be important to incorporate for the environmental, social, and economic stability of the world’s future. As the shift from impervious to pervious surfaces continues to occur, it will be interesting to see the speed at which this concept permeates—how much use and what technological advances will we see out of the next generation to come?

Notes

1 An earlier version of this article appeared in the June 2010 issue of ROOT. (back to top)

2 For more, see www.lowimpactdevelopment.org. (back to top)

Katie McKain, ASLA, MLA, MUD is a proponent for sustainable design and green initiatives who promotes stormwater management principles as a representative for Sustainable Paving Systems, LLC. She earned her Master of Landscape Architecture and Master of Urban Design at the University of Colorado Denver in Denver, CO, and her Bachelor of Science from Purdue University in West Lafayette, IN. McKain also received her certification from GREENCO for Best Management Practices for the Conservation and Protection of Water Resources in Colorado. She can be contacted by e-mail at kdmckain@hotmail.com.

This article is full of great information for controlling stormwater runoff! I particularly like the systems that direct the water into bays that promote natural vegetation. Of course, you would need to have the room for something like this. I’m thinking of having a drainage pit installed in my yard. Maybe I can plant some greenery around it, so the excess water doesn’t go to waste.

I like your suggestion to have a rain garden with plants that can survive in wet or dry conditions. That sounds like a good way to use extra water from storms. My husband and I are remodeling the outside of our home, and we’re trying to figure out how we want to deal with drainage. We’ll just have to find someone to do the design of our drainage.

I never knew that gravel and finely crushed rocks were inefficient at controlling stormwater. It makes sense that they would be chosen due to their lower cost. However, I’d rather a more durable material for my driveway.

It’s interesting to learn that when it comes to stormwater that there are some things that need to be looked at when it comes to working with it. I never knew there were different kinds of waters and even common types like phytoremediation that helps removes toxic metals from water. This is something that we will look into more so that we will be able to narrow down all of our options.

Thanks for the very informative article.