How cool surfaces function

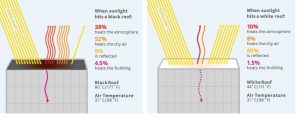

Cool surfaces work by reflecting solar energy rather than absorbing it. The reflected solar energy mostly passes out of the earth’s atmosphere and into space, creating a net cooling effect at the building scale and, when deployed widely, at community, city, and even global scales. Figure 3 summarizes the impact of shifting to a light-colored cool roof. At the building scale, solar-reflective roofs can reduce cooling energy demand by 10 to 40 percent. In winter, the heating penalty may range between five and 10 percent as a function of local climate and building characteristics (e.g. the amount of roof and wall insulation, window-to-wall ratio, etc.). In unconditioned structures, cool roofs result in five- to six-degree reductions in temperatures on the floor below the roof. Cool walls provide similar benefits, at about 80 percent of the level generated by cool roofs. At the building scale, cool roofs and cool walls can contribute to cool air temperature. A comprehensive literature review has found a 0.1 increase in solar reflectance results in a 0.5-degree reduction in average outdoor air temperatures and a 1.5-degree reduction in peak temperatures. Solar reflectance is measured on a scale from 0 to 1, so a 0.1 increase is similar to shifting from a dark- to a medium-grey color.

These potential effects on air temperature can influence the formation of ozone. A decrease in air temperatures tends to correlate with a reduction in the amount of ozone formed, and thus an overall improvement in air quality. The relationship between air temperature and air quality is a complex one. Some of the air-quality improvements from reduced ozone formation may be offset because reduced air temperatures near the urban surface may slow wind speeds and vertical mixing of air with higher air levels, leaving some pollutants near the ground. That said, the amount of air-temperature reduction needed to trigger this effect at a significant level is not practically achievable by simply adopting cool roofs.

A recent analysis of the potential benefits of passive cooling in Los Angeles, California, highlights just how important even small changes in average air temperature can be. Researchers studying the potential impact of passive cooling on mortality during historic heat waves found the indoor and outdoor cooling resulting from highly reflective roofs and vegetation areas could have saved one out of four lives lost during these heat waves and would delay climate change-induced warming by 25 to 60 years.

A real-world case of the effect of large-scale deployment of cool surfaces comes from Almeria, Spain (Figure 4, page 26), which has a unique tradition of whitewashing its greenhouses in preparation for summer weather. Almeria has more than 27,113 ha (67,000 acres) of land area covered by greenhouses, making it one of the largest concentrations of greenhouses in the world. The region reflects substantially more sunlight than neighboring regions with fewer whitewashed greenhouses. A 20-year longitudinal study comparing weather-station data in Almeria to similar surrounding climatic regions found average air temperatures in Almeria have cooled 0.7 degrees, compared to an air temperature increase of 0.5 degrees in the surrounding regions lacking whitewashed greenhouses—a 1.2-degree difference.

Cooling buildings and cities directly addresses the many negative effects associated with rising temperatures. Valuing those many benefits shows every dollar invested in cool surfaces generates $12 in net economic gains. Beyond the economics, the negative effects of heat are overwhelmingly borne by low-income communities of color. Thus, a concerted effort to deploy cool roofs (and other passive measures) will meaningfully contribute to efforts to improve social and racial equity.

Key factors to consider when planning to install a cool roof

While cool roofs are applicable and deliver benefits in all but the coldest climates, there are a few issues—all relatively minor—to consider when determining which type of roof to install.