Designing spandrel glass

by Katie Daniel | March 8, 2017 10:19 am

[1]

[1]by Steven D. Marino

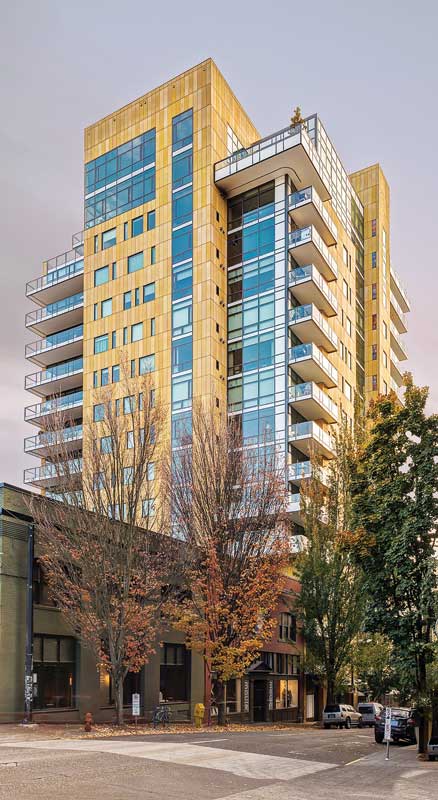

Among the many reasons architects specify glass are its beauty and versatility. In addition to offering the full spectrum of transparency, color, and high environmental performance as vision glass components, this material can be opacified in spandrels to create visual flair on building façades while hiding unsightly interior features such as hung ceilings, knee-wall areas, between-floor voids, mechanical equipment, wires, vents, and slab ends. Although glass spandrels have been popular on building façades for decades, there are technical factors design professionals must account for when specifying these assemblies.

Through the application of coatings, film, or other materials to the indoor surface of a glass lite, glass spandrels block light and prevent transparency. In monolithic and insulating glass unit (IGU) spandrels—the two most common types—ceramic enamel frits, silicone-based paints, and plastic or metal films are affixed to or installed just behind the glass substrate to make it opaque.

Shadow box spandrels are a third alternative. Unlike the aforementioned conventional spandrels, these assemblies incorporate transparent glass and unite it with a separate insulating component. In most cases, this component is a rigid foil-backed material, taped to the surrounding framing system to prevent the passage of light.

Although monolithic and IGU spandrels are typically specified to enhance the building’s appearance, it is usually impossible to create a seamless color match between spandrel glass and vision glass on a façade with these types of units. However, because they can be fabricated with an almost limitless palette of opacifier colors, monolithic and IGU spandrels are ideal for complementing vision glass and other building finishes such as metal, brick, concrete, and stone.

If a strong color match between vision glass and spandrel glass is desired on a building exterior, using shadow box spandrels is recommended.

Monolithic glass spandrels

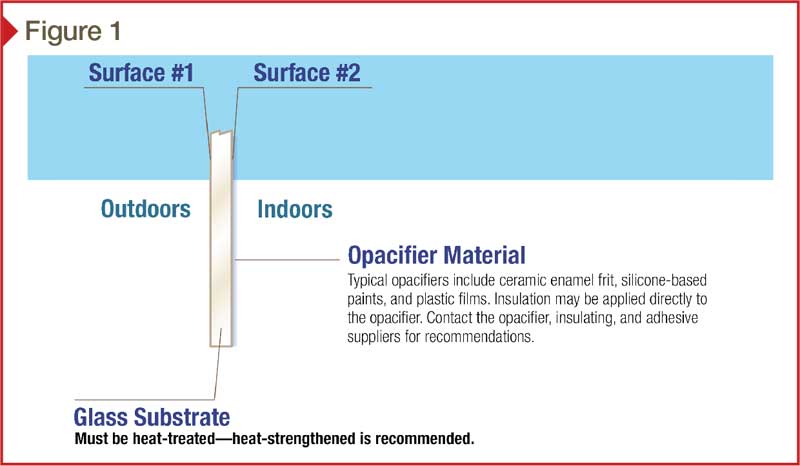

Monolithic glass spandrels are the most basic spandrel variety, consisting of a coated or uncoated glass substrate to which an opacifier is applied, as seen in Figure 1.

[2]

[2]Images courtesy Vitro Architectural Glass

Most manufacturers recommend all glass specified for monolithic spandrels be heat-strengthened to provide the mechanical strength needed to resist wind load and thermal stresses. The inherent break pattern of heat-strengthened glass is another reason for this recommendation, as broken heat-strengthened glass is much more likely than annealed (i.e. non-heat-treated) or fully tempered glass to remain in place until it can be replaced.

Whether heat-strengthened or fully tempered, heat-treated glass products are produced in a similar fashion and using the same processing equipment. The glass is heated to approximately 650 C (1200 F), then force-cooled to create surface and edge compression. The cooling rate of the glass determines if it is heat-strengthened or fully tempered—to produce the latter, cooling is much more rapid, creating higher compression; for the former, cooling is slower, resulting in a compression lower than fully tempered glass, but higher than annealed.

As indicated in Figure 1, insulation is often used in conjunction with spandrel glass. When the insulation is to be applied directly to the opacified surface of the spandrel glass, it is important to work with a glass spandrel fabricator, as well as the adhesive and insulation suppliers, to ensure these products are compatible with the opacifying material. These suppliers can also recommend the best installation procedures for ensuring long-term performance and appearance.

[3]

[3]Insulating glass unit spandrels

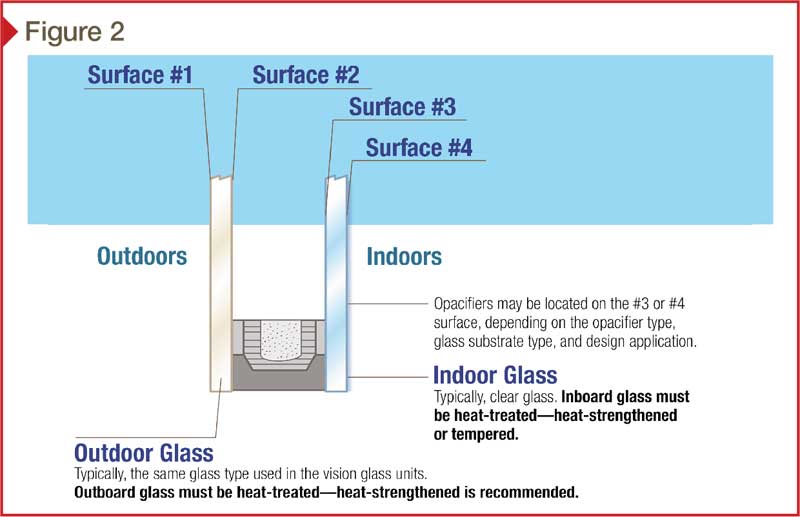

IGU spandrels are fabricated with an opacifying material applied to the third or fourth surface of the indoor glass lite, labeled 3 and 4 in Figure 2.

As these types of spandrels are designed to function like conventional IGUs, with the goal of improving a building’s energy efficiency, they are commonly specified with low-emissivity (low-e) coatings.

When this is the case, specifiers must give special consideration to which surface locations of the IGU are specified for the low-e coating and the opacifier because of the potential these materials have for elevating temperatures within the assembly. For IGU spandrels with low-e glass, the recommended location for the opacifying material is the indoor surface of the indoor lite of glass (Surface 4 in Figure 2).

Another design alternative is to place the low-e coating on Surface 2 of the IGU and the opacifier on Surface 3. As the low-e coating, opacifier, and sealants occupy the same space in this type of spandrel assembly, it is critical to confirm their compatibility with their respective manufacturers.

In some instances, it is possible for an improper combination of materials in the IGU air space to produce volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which can then condense on the low-e coating and cause it to degrade, voiding any applicable warranty.

Precautions should also be taken with spandrel assemblies combining low-e coatings and medium- to dark-colored opacifier coatings. Depending on their location and orientation to sunlight, it is possible for these spandrel designs to generate exceedingly high glass temperatures that can expose the assembly’s interior lite to potentially destructive levels of thermal stress.

Proper design will mitigate the potential for excess concentration of solar heat within the spandrel assembly. The location of the insulating material can be adjusted, and suitable levels of air circulation behind the IGU enabled.

[4]

[4]Photo © Kris Vockler. Photo courtesy ICD High Performance Coatings

As with monolithic glass spandrels, using heat-strengthened glass for both of the lites in the IGU is recommended. Additionally, if the outdoor glass lite of any vision unit on a building façade is tinted, the outdoor lite of any adjacent spandrel units should be the same tint, and a neutral-color opacifier should be specified for Surface 3 of the indoor lite. Doing so is primarily for appearance, although it is important to note tinted glass can contribute to a thermal stress risk because of its increased solar absorption. For this reason, it usually requires heat-treatment.

Insulation and glass recommendations

As the name suggests, insulating materials are typically used in spandrel IGUs. Depending on the glass type and the recommendation of the spandrel fabricator, insulation may be applied directly to or positioned 25 to 50 mm (1 to 2 in.) from the glass surface.

Similar to monolithic glass spandrels, if the insulation material is to be applied directly to the glass surface, specific recommendations regarding its compatibility with the glass, sealants, and other materials inside the spandrel IGU should be solicited from the participating suppliers.

Given that insulation is typically designed to trap and potentially enable solar heat buildup, design professionals should consider using fully tempered glass for the interior lite of the spandrel IGU. This reduces the probability of thermal stress-related breakage, and even if breakage does occur, the exterior layer should prevent fall-out. However, fully tempered glass should not be used for the exterior ply of an IGU unless mandated by code, because of the fall-out potential if it breaks. As always, heat-strengthened glass is recommended for the exterior lites of these units.

Shadow box spandrels

Shadow box spandrels are typically specified for applications where achieving a color match between the vison glass and spandrel glass on a building façade is desired.

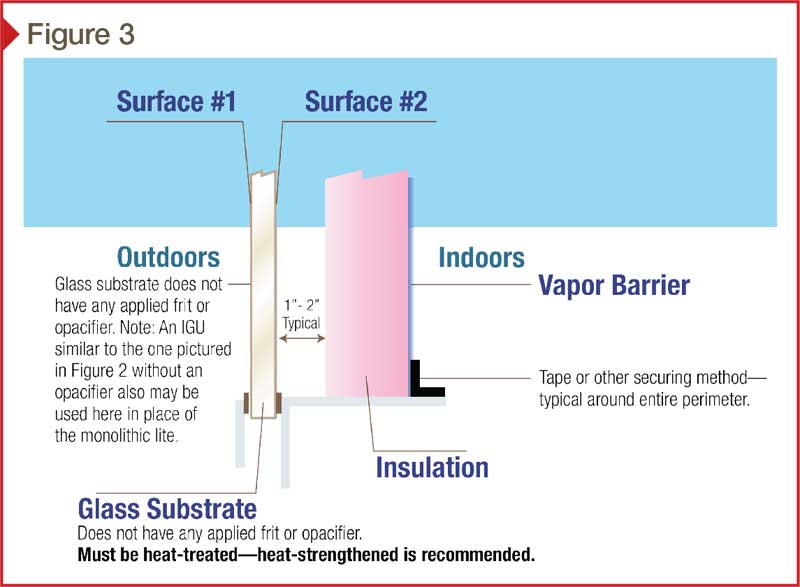

As shown in Figure 3, a shadow box spandrel will typically incorporate:

- a monolithic lite of tinted or low-e coated, heat-treated glass without an opacifier—usually the same color as the adjacent vision glass; and

- an insulation assembly made with black or dark-colored, rigid foil-backed insulation material installed 25 to 50 mm (1 to 2 in.) behind the spandrel glass, with the foil backing facing the interior of the building.

[5]

[5]Image courtesy Vitro Architectural Glass

To completely seal each spandrel glass perimeter, create a moisture/vapor barrier, and block the entry of stray interior light into the spandrel area, the foil surface of the insulation should be secured to the interior surfaces of the glazing system. This is typically done with aluminum tape.

Given that insulation material tends to be dark and even in texture—and because the glass has reduced light transmittance—it is extremely difficult to see insulation through the glass of a shadow box spandrel, except under rare daylighting or sky-viewing conditions.

Shadow box spandrels are appealing because of their color-matching versatility, but architects, designers, and specifiers should be aware of the field-related issues common to these products, and work with suppliers to address them.

It is important to note thermal and optical performance values are calculated using steady-state conditions, and do not take into account the potential dynamic conditions that could exist in the space between glass and insulation in a shadow box spandrel design.

[6]

[6]Photo © Jim Schafer. Phout courtesy Vitro Architectural Glass

Condensation

When there is a large difference between lower outdoor and higher indoor temperatures, shadow box spandrel designs are sometimes prone to creating moisture/vapor pressure differences across the insulation. Insulation, which is included to act as a barrier to the unconditioned space behind the shadow box, does not necessarily help the glass perform better, although it can enhance the performance of the entire package. It can also act as a vision-blocking medium if no opacifying material is used on the glass.

Rips, tears, or holes in the insulation foil backing, the aluminum securing tape, or other unsealed areas (as well as improper tape installation) can create paths for moisture to migrate through the insulation into the shadow box air space. When this happens, and the temperature of the indoor glass surface (i.e. Surface 4) reaches dewpoint, the resulting moisture condenses on the glass. Under certain viewing conditions, it becomes visible from the outside, marring the appearance of the spandrel.

Even when spandrel boxes are fabricated with a perfect vapor barrier, moisture can infiltrate the air space through weep holes, breaches in the pressure-equalized glazing system, or leaks in the glazing system joints.

Over time, repeated cycles of condensation and drying may cause moisture residue to accumulate and permanently stain the glass. In addition to ruining the appearance of the spandrel, condensation cycling has the potential to irreversibly damage the glass, the coating, or both.

Debris and glazing lubricants

Between the time spandrel glass is glazed and the time insulation is installed, windborne dirt, fireproofing materials, and other construction debris can accumulate on the indoor surface of the glass. In addition, during construction of a building, water can collect on concrete decks and become infused with concrete dust and other alkalis.

When these waterborne materials come in contact with uninsulated spandrels, the spandrels may be contaminated with chemicals that can damage the glass or coating and create difficult-to-remove stains. Even when cleaning and stain removal on exposed units are successful, a faint residue may remain on the glass, becoming visible under certain viewing conditions.

Also, in dry glazing systems, lubricants are typically required to effectively install the indoor glazing wedge. If these lubricants are not carefully and thoroughly removed, they can leave visible deposits on shadow box spandrel glass.

[7]

[7]Photo © Kris Vockler. Photo courtesy ICD High Performance Coatings

VOC accumulations

Sealants, paints, and other materials used to manufacture and install insulation materials, glazing sealants, and glazing gaskets in shadow box spandrels often contain volatile compounds and chemicals that can be discharged under certain atmospheric conditions, such as exposure to high temperatures.

In shadow box air spaces on sunlit elevations—where temperatures can easily surpass 71 C (160 F)—these materials can be released, then condense on spandrel glass when temperatures fall. The resulting deposits can accumulate over time, causing stains and risking permanent damage to the glass and coating.

For this reason, specifiers should ensure all materials used in a spandrel assembly are:

- tested by participating suppliers for VOC releases; and

- approved/warranted for shadow box spandrel applications.

Improper insulation installation

When insulation is installed so it contacts spandrel glass, even in a small area, increased glass temperatures or ‘hot spots’ are likely to occur. This increases the probability of thermal stress-related glass breakage, as extreme differences in temperature gradients on a glass surface may force tension stresses to occur.

In addition to increasing potential for glass failure, hot spots can create localized color distortion, damage the coating, or cause water to accumulate where insulation touches the glass, forming residue and staining the glass.

Conclusion

Architects favor vision glass for the transparency and energy-efficient beauty it bestows on buildings. Glass spandrels provide a versatile, colorful, non-transparent tool for hiding the machinery and mechanicals that make designs functional.

By understanding the available spandrel glass options and their technical challenges, architects can help ensure the glass spandrels they specify will maintain functional integrity and attractiveness throughout a building’s lifespan.

Steven D. Marino has more than 30 years of experience with Vitro Architectural Glass (formerly PPG Flat Glass), in both automotive and architectural glass. He has held positions in manufacturing, quality, and other technical roles, including his current post as manager of technical support in Vitro Glass’s technical services department. Marino has a degree in mechanical engineering from Youngstown State University. He is an active member of both the Insulating Glass Manufacturers Alliance (IGMA) and Glass Association of North America (GANA), and sits on multiple committees and task groups for both organizations. Marino currently sits on the GANA Board of Directors as secretary and chairs the GANA Tempering Division Technical Services Committee. He can be reached at smarino@vitro.com[8].

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/spandrel_Edmonton.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/spandrel_figure1.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/spandrel_figure2.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/spandrel_Louisa.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/spandrel_figure3.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/spandrel_MG_9162a.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/spandrel_Casey.jpg

- smarino@vitro.com: mailto:smarino@vitro.com

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/designing-spandrel-glass/