by Carolina Albano

Architects specifying materials for building or remodeling projects consider the performance and aesthetics of construction products, along with material, labor, and installation costs. Too often, however, budget trumps appearance—especially when the client aims for a high-end look.

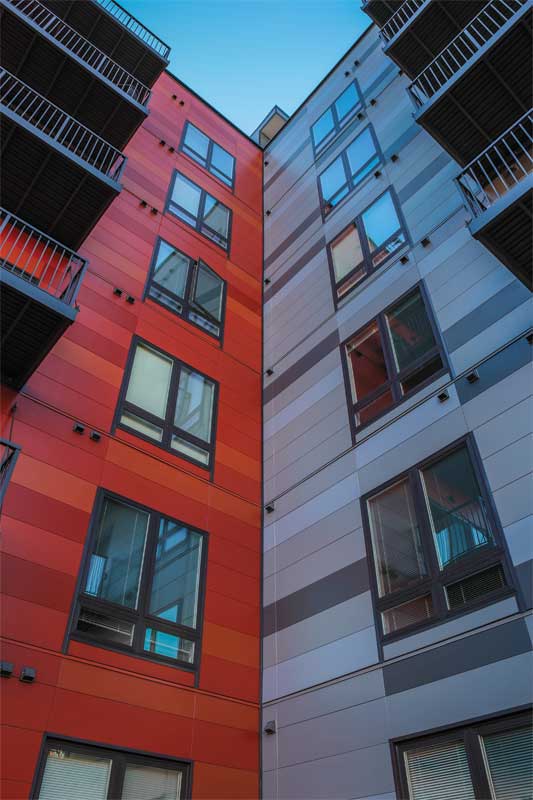

For commercial projects in well-established neighborhoods, the look of the exterior cladding is gaining in importance, as local code officials increasingly insist on structures complementing nearby façades and building owners aim to appeal to younger tenants hoping to live or work in hip, unique surroundings. Still, project budgets are often too limited for the sleek metals, exotic woods, and distinctive stone that lend to an eye-catching elevation.

In response, more design professionals are considering architectural wall panels made from fiber cement. Specialized cladding manufacturers are able to fabricate these products in a variety of textures, styles, colors, weights, and thicknesses—usually at more affordable prices than traditional materials for exteriors.

A pair of student housing structures near universities in Minnesota and Wisconsin, for instance, demonstrates the trend toward replacing aluminum with fiber-cement panels sporting a smooth, satin texture and shimmery topcoat, or substituting fiber-cement lookalikes for concrete masonry units (CMUs).

Developers of the newly built Aguilera Student Housing Apartments in La Crosse, Wisconsin, reported they saved approximately 40 percent on cladding materials by substituting fiber-cement panels for terra cotta and aluminum panels. Likewise, the four-story, 66-unit Riverton Community Housing cooperative, built on a tight site in Minneapolis, complied with local zoning restrictions by specifying durable fiber-cement panels.

The city of the Minneapolis required durable materials for building façades, and since fiber cement is flexible by nature and presents a high-quality look, it was the only option that could adhere to the city’s requirement. With a nod to the building’s student tenants, architects chose three custom colors in a dramatic, bright-yellow façade finish.

Proven formula

For more than two decades, fiber cement has been chosen as an affordable, sustainable, and durable lap siding for residential construction. More recently, the product—in the form of architectural wall panels—is becoming a popular choice on the commercial side, largely because of the ease and comparatively low cost with which manufacturers can fabricate it to mimic wood, stone, brick, metal, and concrete. In comparison to traditional materials, fiber cement is also cost-effective for long-term use. It requires only minor routine cleaning or maintenance and does not need re-sealing or re-coating.

In comparison to traditional materials, fiber cement is also a lighter material to transport and install. For example, some manufacturers offer brick-like panels as light as 19 kg/m2 (3.9 lb/sf), offering the timeless appeal of traditional brickwork without the laborious installation.

Although various manufacturers offer fiber-cement panels in a range of sizes and styles, the basic product is a composite of water, wood pulp, fly ash or silica, and Portland cement. As a cladding product, it requires little maintenance; it resists rot, fire, and termites while also warding off wind, sun, humidity, and cold weather. The material can be manufactured to look like stucco, wood, metal, stone, or brick, but at an overall lower cost and the material arrives on site as a prefinished panel.

Some manufacturers offer products that allow contractors to install 0.8 or 1.4 m2 (9 or 15 sf) at one time, offering contractors a reduced installation time and cost savings on labor since there is no need for masonry. Fiber cement is also durable, with some manufacturers warranting architectural wall panels for 50 years.

Organic wood fiber, which manufacturers take from recycled and virgin sources, allows the panels to be flexible, resilient, and less brittle than earlier versions. Portland cement, usually made from limestone, clay, and iron, securely binds the wood fibers and leaves the finished product strong and rigid. Silica—a component of sand—and fly ash are fillers that reduce the weight of the panels. Some manufacturers mix water into the formula.

The mixture is pressed and processed into panels of varying sizes, lengths, and thicknesses. They can be pressed to create textures like ridges, or molded to take on the appearance of wood grain, brick, or stone. Some manufacturers add decorative factory finishes and colors, and all apply protective coatings.

Commercial-grade fiber cement is different from the material used by residential builders. For homes, fiber cement replaces traditional wood siding. Like other residential claddings, it is screwed or nailed to the building and does not require the advanced moisture management necessary for commercial buildings. Installers do not need specialized training in product installation.

Fiber-cement architectural wall panels for commercial buildings, in contrast, generally require an engineered installation system that renders them as a rainscreen. Easy to install by experienced siding contractors, the architectural wall panel system acts as a barrier against moisture. An air gap between the cladding and the substrate—all part of the same system—forces any moisture finding its way behind the panel to drip down the back of the product and out through weep holes punched at the bottom. The water then drains away from the building or evaporates.