Dispatch from Alaska: Insights on moisture, soil, and material performance

Thaw damage to roadbeds and runways should not be confused with damage caused by freezing or the frost heaves which occur when water gets under a paved surface and freezes. As the ice expands, it creates raised bumps in the roadbed, which become unsupported once the ice melts when temperatures warm. When the permafrost—the foundation upon which the roadway is placed—thaws, the roadway becomes unstable much further below the road surface. One way to help protect permafrost is to take steps to ensure the road stays as cold as possible. This includes insulating embankments and paved areas, along with selecting materials that encourage cold air to flow within the embankment. These measures help keep underlying layers cooler by preventing the transfer of heat further into the ground.4 Insulation also has been used to help prevent the development of frost heaves.

Project overview and material collection

Although there have been several studies examining the use of XPS and EPS insulation, they tend to focus on short spans of time rather than extended use and less harsh exposure, such as vertical applications in walls.

An initial study looking at this topic was done in 1986 by David Esch, with early work in Canada done by Pouliot and Savard in 2003. The findings from the most recent examination of projects in Alaska expand the data set established by these two projects and the analysis work of Cai, Zhang, and Cremaschi done in 2017.6,7,8

The Esch study examined 18 samples from eight sites in Alaska. The XPS insulation came from six locations, averaging nine years of service life, with the longest service life going up to 20 years. The EPS insulation had been in place from three to 15 years. Both insulations were checked for water content and long-range R-value. Samples of XPS insulation were found to have an average water content of 1.16 percent by volume, with individual samples ranging from 0.23 to 2.38 percent, while the average water content in the EPS insulation was 2.9 percent by volume, with individual results ranging from 1.18 to 5.88 percent. The average long-range R-value of XPS insulation was 3.9, while the average R-value for EPS insulation was 2.6.

Similarly, Pouliot, and Savard examined the performance of EPS and XPS at locations in Canada. They considered the insulations’ water uptake and thermal conductivity. Insulation samples had been in situ for one, three, five, and seven years, and the thermal conductivity of the material was checked against a sample taken at the time of construction. The evaluation found that average thermal conductivity for EPS was 0.036W/K*m (0.250 BTU in./hr sf F), while it was 0.030 W/K*m (0.208 BTU in./hr sf F) for XPS insulation. Stated another way, the R-value is 4.000 for EPS and 4.808 for XPS.

Current testing standards which limit predictive assessments

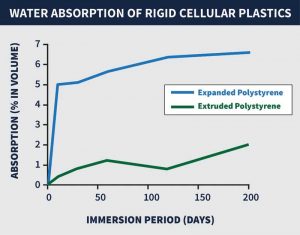

A Canada-based research team also conducted water absorption trials using ASTM D2842, Standard Test Method for Water Absorption of Rigid Cellular Plastics.9 The water immersion tests found EPS absorbed about five percent water by volume in 10 days, a pace which slowed to a total of 6.2 percent water by volume after 200 days. In contrast, following 200 days immersion time, the XPS insulation collected two percent moisture by volume (see Figure 1).

While such testing is the approved standard, Connor notes this testing does not serve as a good indicator of a material’s performance in situ. “Just submerging insulation is not a good indicator of its performance in locations, such as a building’s roof or in the ground,” he says. “What we really want to know is what a material’s R-value is likely to be in service. I do not care about performance in the factory; I care about how it’s going to perform in the soil over time.”

Thus far, no testing has measured vapor pressure in the ground; however, the area is inspiring additional research. Connor adds how, beyond tests designed to better reflect real-world conditions, the industry needs more predictive tools to evaluate the performance of insulation and other materials in various locations. Unlike situations when insulation is used in walls, when used in below-grade situations, insulation does not dry after it starts collecting moisture. This difference makes testing which involves drying samples less relevant than it would be in other situations. Once wet, insulation in the ground will stay moist and continue to see performance influence from water.

Understanding moisture’s migration into insulation

In 2017, Cai, Zhang, and Cremaschi examined how water absorption happens with rigid foam board insulation when it is used in buildings.8 In those situations, the properties of absorption, diffusion, and capillary action occur. When humidity is 30 percent or below, absorption has been the main method of water transfer, and when humidity is above 80 percent, capillary action becomes primary.