The research team also looked at the type of tests used with insulation, noting that while the four-day immersion test ASTM D2842 could indicate a water content for EPS close to what is found when the insulation is in place for less than six years, it tends to underpredict the moisture content for XPS. As Connor observed, they suggest immersion tests are not an accurate way to predict long-term performance for either type of insulation when used below-grade in roadway scenarios. However, their results did indicate how the four-day immersion test could be used to provide a quality control (QC) test.

Connor’s new research sought to add data to the previously established points by collecting and evaluating additional samples of insulation. Recent changes to the makeup of EPS insulation (a coating was added to the top and bottom of the material) also were examined. Insulation samples were gathered from three locations:

- Dalton Highway, originally placed in 2013 (EPS)

- Cripple Creek, originally placed in 1997 (EPS)

- Golovin Airport, originally placed in 1987 (XPS)

Insulation samples were excavated and sealed in polyethylene bags before being sent for third-party testing. All samples saw 6.4 mm (0.25 in.) of material trimmed from each side before testing to remove soil contamination and damage. Insulation was tested for thermal performance in accordance with ASTM C518, Standard Test Method for Steady-State Thermal Transmission Properties by Means of the Heat Flow Meter Apparatus.10 Following thermal testing, samples were dried to establish moisture content and selected samples were checked for thermal performance post drying. Individual data points were collected and included with existing data tables.

| CONSIDER THE TESTING PROCESS |

| It has been said that there are many solutions to a problem. With that wisdom in mind, AEC pros should consider that while multiple products or assemblies may meet pass or fail criteria for minimum assembly performance, such as a weather resistive barrier system, some product property testing may not be an equal comparison when evaluating the components of the assembly. Insulation provides a good example.

The procedures to test liquid moisture absorption of an insulating material may appear to be equal in nature, however closer evaluation of the testing methods used reveal significant difference in performance. For example, an insulating material claiming to deliver “superior water resistance” was tested to ASTM C209 for moisture absorption—requiring submersion of the specimen beneath water for a period of two hours followed by a draining period before weighing to specimen to determine moisture absorption. This resulting number is commonly referred to as simply “moisture absorption” on a product data sheet. However, two other types of rigid foam plastic insulation were tested to ASTM C272. While the process may seem similar—submerging the specimen in water, weighing the specimen and then reporting moisture absorption percentage by weight—the exposure time is significantly increased—from two hours to twenty-four hours and no time is allowed for draining. Based on this example, it is critical to compare not just physical property performance on a data sheet, but the actual test methods referenced in producing those performance results. While the products may both be used in a weather resistive barrier system, one is clearly more susceptible to moisture absorption in the unfortunate event of significantly water exposure or damage to a protective facer. |

Water movement in soil

Water movement through soil is a complicated topic, as movement is tied to factors including soil gradient, moisture content, soil suction, and temperature gradient. Vapor pressure can also be involved in moisture movement. For example, damp soils in cold climates see moisture move upward using capillary action and vapor transport based on the thermal gradient in the ground. Moisture may freeze, prompting frost heaving to occur. Vapor pressure also may push moisture to move, especially in silty or finely grained soil. It may also prompt moisture intrusion into insulation based on the role it plays for moisture absorption in building envelopes. While the work at the University of Alaska focused on the harsh permafrost conditions, a similar phenomenon occurs in Arizona’s notoriously hot climate, as vapor moves upwards through the soil during the day, then cools and condenses beneath the pavement at night.

The understanding of soil mechanics in unsaturated soils has been improving. However, this has yet to be applied to the use of insulation in soil, so questions remain regarding the mechanisms and performance of foam board insulation in below-grade applications in harsh climates. “Soil’s strength is largely a function of its moisture content,” says Connor. “If we understood moisture’s behavior in soil better, we could alter the gradation of soil and manage the moisture moving through it.”

Another challenge of current moisture testing is it does not account for the difference between lateral movement which may occur in walls, versus the more vertical movement taking place as water rises and falls in the ground. Reflecting on the Dalton highway work, Connor stated, “It was really surprising to see how much moisture was sitting on the surface of the insulation, and it got us thinking about how moisture is moving around in the soil.”

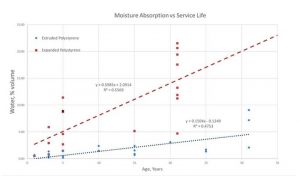

Despite the lack of thorough understanding regarding moisture movement through non-saturated soils, testing and examination of the collected insulation samples provided data regarding how much moisture the insulation absorbed throughout its service life.