Setting standards for materials, equipment, and the environment

Establishing room design criteria is also a vital facet of the early phases of design. Room criteria sets the stage for selecting sustainable materials and finishes and for meeting MEP (mechanical, electrical, and plumbing) requirements. Although standards and codes must be followed, they sometimes allow for interpretation. For example, when choosing between epoxy flooring and rubber flooring, rubber offers sustainability. It is renewable, low volatile organic compounds (VOCs), anti-slip, bacteriostatic, and is washable with water rather than chemicals. However, rubber is not always appropriate or allowable in all cases.

Remember the building systems

Research and development facilities often require reconfiguration to keep pace with changing research. At a Fortune 500 corporation, reconfiguring 42 lab arrangements over three years cost $2.7 million. At the firm’s new innovation development center, preassembled modules were designed to provide all major MEP infrastructure throughout the labs. The modules were the MEP infrastructure “fingers” throughout the space, providing water and lab gasses, electrical bus duct, telecom cables, and exhaust ductwork.

Technicians can quickly connect hood ventilation lines in a variety of locations. Ten percent of the hoods were reconfigured within 18 months. It would have cost $750,000 if this new facility had the design of the previous one, and this estimate does not include the considerable design, demolition, and reconstruction cost that would have been necessary. Modular design allowed these configurations to occur in a matter of days, at no additional cost. Prefabrication also accelerated the construction schedule, reducing costs by more than $70,000 and saving more than 3000 on-site labor hours.

Case study: McCourtney Hall

McCourtney Hall at the University of Notre Dame exemplifies how early planning helped establish a high-profile, flexible, and collaborative lab space.

The building houses combined labs for the colleges of science and engineering, and supports analytical sciences and engineering, chemical and biomolecular engineering, and drug discovery. This building is meant as a high-profile home for advanced research. It encourages collaboration between different fields and inspires novel research while providing a foundation for original research that might not have occurred in a more traditional, siloed setting.

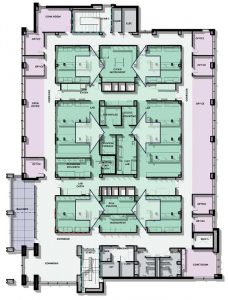

McCourtney Hall is approximately 18,580 m2 (200,000 sf), one-half of which consists of open lab and team spaces. It has a collaborative core for offices and informal interaction. Forty percent of the building was initially reserved as shell space but is now almost entirely built out. The project cost $56 million to build, or about $280 per gross square foot. The building occupies four floors with a basement level and a mechanical penthouse on top.

Interdisciplinary design made this project possible. From its beginning, there were four major goals: architectural impact, Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification, systems flexibility, and energy conservation. For architectural impact, the idea was to make a statement on campus while establishing a modern laboratory presence. The project initially had a minimal target of LEED Silver. The systems needed to support a broad range of cutting-edge research and adapt to research needs over the next 50 to 100 years. Conserving energy was essential for this high-energy usage building type, which was achieved by focusing on responsive controls that deliver energy and services when and where they are needed.

Early planning and architectural drivers help support those project goals. McCourtney Hall is a foundational building in establishing a presence in a newly developed area of campus, as part of the master plan. One idea was to blend the exterior design with the campus’ style, which is akin to Collegiate Gothic. The building needed to provide a program to meet the needs of two different schools, while encouraging cross- pollination and collaboration in research between them. It also needed to make a statement to help put Notre Dame on the map and attract top research talent. McCourtney Hall is the cornerstone of what Notre Dame envisions as a new research and development quad. Early on, engineers helped establish the new campus utility distribution loop to this quad, one that uses the campus’ geothermal development.

From an exterior architecture standpoint, the university challenged the design team to create a building that looked like it has been around for 100 years, then renovated to become a modern lab. The design team adapted this Collegiate Gothic style to accommodate the modern laboratory program. They installed gables to conceal the fans and hide the heavy HVAC equipment needed to support the lab.