Other positive attributes of precast concrete that are not reflected in a cradle-to-gate EPD relate to its contribution to improved energy efficiency. For example, precast concrete components can contribute to a structure’s energy efficiency due to its inherent thermal mass. This property of the precast concrete can delay and reduce peak heating and cooling demands in most climates, which can enable smaller HVAC equipment and absorb heat generated by people and equipment on the inside surfaces.

Therefore, although EPDs are useful in evaluating some sustainable attributes, they should not be the only tool used when making product choices. To compare structural or more complex systems, it is nearly impossible to create an EPD for every possible combination of performance requirements. Instead, for a given structure, it is best to compare environmental impacts of a full structure level for a full lifecycle.

LCA case study

In 2009, the Precast/Prestressed Concrete Institute (PCI) sponsored a cradle-to-grave comparative LCA of a commercial building, which was built using three different structure types and five different envelope types.11 The goal of the project was to better understand precast concrete’s environmental lifecycle performance in mid-rise buildings relative to alternative structural and envelope systems in four U.S. locations. Based on the U.S. EPA tool for the Reduction and Assessment of Chemical and Other Environmental Impacts (TRACI) impact assessment method, the following environmental impacts were assessed:

- GWP

- Acidification potential

- Eutrophication potential (EP)

- Photochemical smog creation potential (POCP)

- Ozone depletion potential (ODP)

| A NOTE ABOUT EMBODIED CARBON |

| A lifecycle assessment (LCA) evaluates a full set of environmental impacts over the full life of a product or system. Both core product category rule (PCRs), and subcategory PCRs list the minimum environmental impact categories and other information that must be evaluated and then reported in an environmental product declaration (EPD). Minimum environmental impacts that must be reported in an EPD include:

• Global warming potential (GWP) The total GWP of the system is the sum of the embodied carbon and the GWP attributed to the use-phase (operational) energy use. Alternatively, interest in embodied carbon is emerging as an indicator of a limited environmental impact (GWP only) over a limited number of lifecycle stages. |

In the study, the functional unit (basis of comparison) was a five-story commercial office building that meets minimum building energy code requirements and provides conditioned office space for approximately 130 people. The service life of the building was assumed to be 73 years, which is the median life for large commercial buildings in the U.S. supported by the literature.

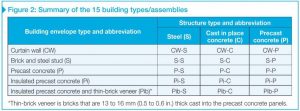

Figure 2 provides a summary of the 15 building assemblies evaluated in the study, which includes five variations of building envelope and three variations of structure, modeled in four U.S. climate zones, in the representative cities of Denver, Memphis, Miami, and Phoenix.

Although five midpoint environmental impacts were assessed, only the GWP results are presented in this article. Figure 3 (page 33) presents the cradle-to-gate GWP results of the 15 structure-and-envelope combinations for each of the four representative cities. For all four cities, the precast concrete structure with curtain wall envelope system had the highest GWP on a cradle-to-gate basis. If that system were being selected based on cradle-to-gate GWP alone, it would likely be eliminated. Instead, the steel structure with brick and steel stud envelope, which had the lowest GWP on a cradle-to-gate basis in climate zones 4 and 5, would likely be chosen.

Similarly, in climate zones 1 and 2, the steel structure with insulated precast concrete envelope would likely be chosen due to its lowest GWP on a cradle-to-gate basis in those climate zones.