Evolution of sustainable construction from LEED to federal mandates

by arslan_ahmed | October 13, 2023 4:00 pm

[1]

[1]By Emily Lorenz, PE

With the signing of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA)1 and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA),2 federal funds for infrastructure construction and low-embodied carbon materials will soon be entering the construction pipeline.

An environmental product declaration (EPD) discloses the environmental impacts of a construction material or product over a portion of, or all of, its lifetime. This makes it possible to understand the relative impact of different products and materials. EPDs allow a manufacturer to be transparent with interested parties, such as architects, designers, and specifiers, about its products’ environmental performance.

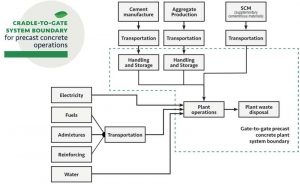

Precast concrete is in a unique position because precast concrete projects are built to last longer than other construction materials. This means considerations other than cradle-to-gate environmental impacts typically reported in an EPD should be evaluated. Cradle-to-gate encompasses the production stage of the lifecycle stage, or modules A1 through A3 (see “Lifecycle stages” sidebar on page 30). Frequently, the overall lifespan of a building must be considered to understand the full environmental impacts of design decisions. Thus, a full lifecycle assessment (LCA) of a building is necessary.

From voluntary transparency to government mandate

Initial awareness of sustainable design and construction in the U.S. can be attributed to the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) rating system, embraced primarily by architects in the design and construction communities. Other voluntary programs have been launched over the last 15 to 20 years, such as the Green Building Initiative’s (GBI’s) Green Globes and the International Passive House Association (iPHA), but none have matched the reach and influence of the LEED rating system.

When the construction industry first started responding to requests for the environmental impact of products, the requests were typically coming from architects wanting to know the recycled, biobased, or regional material content of products. This information was used to document requirements in the LEED rating system, then used to achieve points and ultimately a rating of the final structure.

As the LEED rating system evolved, submittal requests expanded to include requests for EPDs. Through this voluntary program, manufacturers were encouraged to create EPDs in order to transparently report the potential environmental impacts of their products. Manufacturers were further encouraged to produce plant-specific EPDs by rewarding their “value” as twice than that of an industry average EPD toward the number of points or products required. (See more on industry-average versus plant-specific average in the “EPD Basics” section).

[2]

[2]The LEED program moved the needle toward more sustainable products and increased transparency as architects incorporated LEED requirements into project specifications. Although a voluntary program, by implementing requirements into the specifications, product manufacturers had to comply regardless if they wanted to supply products to LEED projects. Thus, LEED was highly influential in raising awareness in the construction industry to topics such as EPDs and environmental impacts.

The latest push toward product transparency is coming from all levels of the government. Starting from the top, in December of 2021, the Biden administration issued Executive Order (EO) 14057, Catalyzing Clean Energy Industries and Jobs Through Federal Sustainability.3 This order sets government-wide goals for federal agencies related to reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, transitioning to carbon-pollution-free electricity and zero-emission fleets, achieving net-zero-emission buildings, and incorporating sustainable acquisition and procurement practices, among others.

Two pieces of legislation were passed that allocated funding to assist in meeting the requirements of EO 14057, the IIJA1 and the IRA.2 The IIJA allocated funding focused on three main areas: repairing transportation projects; improving the resilience of infrastructure to climate change, cybersecurity risks, and other hazards; and implementing quality internet service more equitably. Funding through the IIJA is targeted toward states, local, and tribal agencies, and is less prescriptive than the funding allocated in the IRA.

As part of the IRA, federal agencies were allocated funding for the use of low-carbon materials. The U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) was allocated $2.15 billion to support the installation of low-embodied carbon-materials on construction and renovations projects, while the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) was allocated $2 billion to facilitate the use of construction materials and products that have substantially lower embodied GHGs.

To assist in meeting the requirements of the IRA, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was charged with setting the definition of “low-embodied-carbon materials.” EPA issued its initial determination of “low embodied carbon” in December 2022,4 using a quintile approach. For the purposes of meeting the IRA requirements, EPA states low-embodied-carbon materials are those in the lowest 20 percent percentile of global warming potential (GWP) values when evaluating all possible materials in a product category (relative to the industry average).

GWP, also referred to as climate change potential, “describes potential changes in local, regional, or global surface temperatures caused by an increased concentration of GHGs in the atmosphere, which traps heat from solar radiation through the ‘greenhouse effect.”5 The gases CO2, methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O) are some of the GHGs grouped together in the GWP impact category. GWP is reported in units of kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e).

GSA was the first federal agency to issue draft guidelines related to low-embodied-carbon materials and IRA funding. It issued the draft IRA Low Embodied Carbon Material Standards for concrete, asphalt, steel, glass, and cement in January 2023 with a request for information (RFI) to stakeholders. As of July 2023, GSA’s revised IRA Low Embodied Carbon Material Standards for concrete, asphalt, steel, glass, and cement have not been released.

[3]

[3]The basics of EPDs

In order to qualify as a low-embodied-carbon material and be selected for projects for which GSA and other federal agencies are using IRA funds, manufacturers must create EPDs to show their GWP.

To understand how EPDs are created, one must understand LCA. LCA is an analysis method developed to, among other things, allow the evaluation of the potential environmental impacts of a product system. Through the use of LCA, models are built of the product system to account for material and energy flows through a system boundary, which are then characterized into potential environmental impacts. Changes to that product system can be evaluated to determine if they improve or worsen the environmental impact of the product. Two standards are used to perform LCA: International Organization for Standardization’s (ISO’s) ISO 14040, Environmental management—Lifecycle assessment—Principles and framework,6 and ISO 14044, Environmental management—Lifecycle assessment—Requirements and guidelines.7

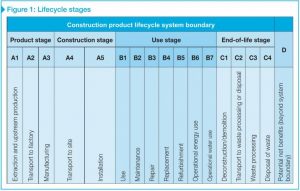

[4]When an LCA is conducted, there is flexibility in the scope of the assessment. One of the more-important scope decisions relates to the lifecycle stages evaluated. Figure 1 shows how various lifecycle stages are categorized in the life of a construction product. At a minimum, all EPDs include lifecycle modules A1, extraction and upstream production; A2, transport to factory; and A3, manufacturing. These modules encompass the “cradle-to-gate” impacts of a product.

[4]When an LCA is conducted, there is flexibility in the scope of the assessment. One of the more-important scope decisions relates to the lifecycle stages evaluated. Figure 1 shows how various lifecycle stages are categorized in the life of a construction product. At a minimum, all EPDs include lifecycle modules A1, extraction and upstream production; A2, transport to factory; and A3, manufacturing. These modules encompass the “cradle-to-gate” impacts of a product.

When an LCA report is developed for a given study, it includes a significant amount of information about the product system and its potential environmental impacts. However, given the complexity of an LCA report, it is not necessarily useful for communicating the potential environmental impacts of a product, which is why EPDs are developed. EPDs are also known as Type III environmental labels (according to ISO 140258) that report a peer-reviewed summary of the results of an LCA.

| LIFECYCLE STAGES |

| There are four lifecycle stages according to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 21930 are: production, construction, use, and end-of-life.9 Each lifecycle stage is subdivided into the following modules: • Production: Extraction and upstream production (A1), transport to factory (A2), and manufacturing (A3). • Construction: Transport to site (A4) and installation (A5). • Use: Use (B1), maintenance (B2), repair (B3), replacement (B4), refurbishment (B5), operational energy use (B6), and operational water use (B7). • End-of-life: Deconstruction/demolition (C1), transport to waste processing or disposal (C2), waste processing (C3), and disposal of waste (C4). |

To create an EPD, an LCA practitioner must use several standards:

- ISO 14040 and ISO 14044 to develop the underlying LCA.

- ISO 14025, Environmental labels and declarations—Type III environmental declarations—Principles and procedures,8 as the core product category rule (PCR).

- ISO 21930, Sustainability in buildings and civil engineering works—Core rules for environmental product declarations of construction products and services9 or European Standard EN 15804, Sustainability of construction works. Environmental product declarations. Core rules for the product category of construction products,10 if the product being evaluated is one for use in a building or infrastructure project.

- A subcategory PCR for the product category, if one exists.

Subcategory PCRs are typically developed by industry associations or collaborations between manufacturers and stakeholders for a given product category. Product categories are typically established based on a Construction Specifications Institute (CSI) MasterFormat designation or standard manufacturing specifications such as those from ASTM International or the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO).

EPDs can be developed for one or more products and for one or more manufacturers. EPDs can be categorized as plant- or producer-specific declarations or as industry-average declarations. Those EPDs classified as “plant-specific” report environmental impacts as an average of:

- One product from one manufacturer’s plant; or

- An average product from one manufacturer’s plant.

“Producer-specific” EPDs report environmental impacts as an average of:

- One specific product from several of a manufacturer’s plants; or

- An average product from several of a manufacturer’s plants.

EPDs that are considered industry-average declarations report environmental impacts as an average of:

- One specific product from several manufacturers’ plants; or

- An average product from several manufacturers’ plants.

To set requirements related to low-embodied-carbon materials that qualify for IRA funding, draft federal agency requirements are setting a maximum GWP value related to an industry-average EPD. In order to qualify as a low-embodied-carbon material and be selected for projects that GSA and other federal agencies are using IRA funds, manufacturers must create plant- or product-specific EPDs to show the GWP of their products.

However, basing product selection on one potential environmental impact category, such as GWP, can increase other environmental impacts and the GWP of other lifecycle stages. In the worst case, this may increase the total GWP of a structure. These concerns are highlighted in the next section with examples related to a precast concrete and an LCA case study.

Seeing the whole picture

There are many sustainable design and construction practices that are not reflected in cradle-to-gate EPDs. For example, precast concrete uses recycled materials, including industrial by-products (fly ash and slag cement) and aggregate fillers (ground limestone), which can reduce the need for portland cement, and which is reflected in an EPD. However, precast concrete is also manufactured locally, reducing transportation impacts to the construction site, and it also reduces construction waste, minimizes site impacts, allows for quicker assembly due to being manufactured off site in a controlled environment. All these attributes are not captured in a cradle-to-gate EPD for precast concrete.

Other positive attributes of precast concrete that are not reflected in a cradle-to-gate EPD relate to its contribution to improved energy efficiency. For example, precast concrete components can contribute to a structure’s energy efficiency due to its inherent thermal mass. This property of the precast concrete can delay and reduce peak heating and cooling demands in most climates, which can enable smaller HVAC equipment and absorb heat generated by people and equipment on the inside surfaces.

Therefore, although EPDs are useful in evaluating some sustainable attributes, they should not be the only tool used when making product choices. To compare structural or more complex systems, it is nearly impossible to create an EPD for every possible combination of performance requirements. Instead, for a given structure, it is best to compare environmental impacts of a full structure level for a full lifecycle.

LCA case study

In 2009, the Precast/Prestressed Concrete Institute (PCI) sponsored a cradle-to-grave comparative LCA of a commercial building, which was built using three different structure types and five different envelope types.11 The goal of the project was to better understand precast concrete’s environmental lifecycle performance in mid-rise buildings relative to alternative structural and envelope systems in four U.S. locations. Based on the U.S. EPA tool for the Reduction and Assessment of Chemical and Other Environmental Impacts (TRACI) impact assessment method, the following environmental impacts were assessed:

- GWP

- Acidification potential

- Eutrophication potential (EP)

- Photochemical smog creation potential (POCP)

- Ozone depletion potential (ODP)

| A NOTE ABOUT EMBODIED CARBON |

| A lifecycle assessment (LCA) evaluates a full set of environmental impacts over the full life of a product or system. Both core product category rule (PCRs), and subcategory PCRs list the minimum environmental impact categories and other information that must be evaluated and then reported in an environmental product declaration (EPD). Minimum environmental impacts that must be reported in an EPD include:

• Global warming potential (GWP) The total GWP of the system is the sum of the embodied carbon and the GWP attributed to the use-phase (operational) energy use. Alternatively, interest in embodied carbon is emerging as an indicator of a limited environmental impact (GWP only) over a limited number of lifecycle stages. |

In the study, the functional unit (basis of comparison) was a five-story commercial office building that meets minimum building energy code requirements and provides conditioned office space for approximately 130 people. The service life of the building was assumed to be 73 years, which is the median life for large commercial buildings in the U.S. supported by the literature.

[5]

[5]

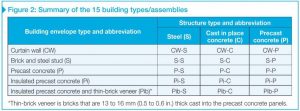

Figure 2 provides a summary of the 15 building assemblies evaluated in the study, which includes five variations of building envelope and three variations of structure, modeled in four U.S. climate zones, in the representative cities of Denver, Memphis, Miami, and Phoenix.

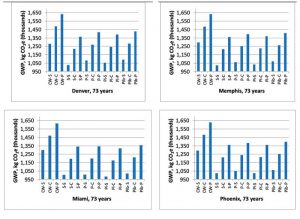

Although five midpoint environmental impacts were assessed, only the GWP results are presented in this article. Figure 3 (page 33) presents the cradle-to-gate GWP results of the 15 structure-and-envelope combinations for each of the four representative cities. For all four cities, the precast concrete structure with curtain wall envelope system had the highest GWP on a cradle-to-gate basis. If that system were being selected based on cradle-to-gate GWP alone, it would likely be eliminated. Instead, the steel structure with brick and steel stud envelope, which had the lowest GWP on a cradle-to-gate basis in climate zones 4 and 5, would likely be chosen.

Similarly, in climate zones 1 and 2, the steel structure with insulated precast concrete envelope would likely be chosen due to its lowest GWP on a cradle-to-gate basis in those climate zones.

[6]

[6]However, when evaluating the environmental impacts for the full life of the building, which adds impacts due to the use and end-of-life phases to those of the cradle-to-gate, there is not much relative difference in GWP between the buildings within a given city. When evaluating the results on a cradle-to-grave basis, Figure 3 and the data show:

- In Denver, GWP varies from 58 to 62 million kg (127 to 136 million lb) CO2e, and the coefficient of variation (COV) is 2 percent.

- In Memphis, GWP varies from 45 to 46 million kg (99 to 101 million lb) CO2e, and the COV is 1 percent.

- In Miami, GWP varies from 50 to 51 million kg (110 to 112 million lb) CO2e, and the COV is less than 1 percent.

- In Phoenix, GWP varies from 44 to 46 million kg (97 to 101 million lb) CO2e, and the COV is 1 percent.

[7]

[7]It is evident that any increased cradle-to-gate GWP is offset by reductions in the operational phase GWP for each climate zone. This is why it is important to evaluate design choices based on a full lifecycle and within the building context. In this study, there was not a significant difference in the lifecycle environmental impacts between steel, cast-in-place concrete, and precast concrete structural systems.

Viewing EPDs as one tool

Voluntary green rating systems and now federal legislation have created a tremendous need to get environmental-impact information into the hands of owners and designers. EPDs have been singled out as the tool to evaluate the sustainability of products. As the case study illustrated, making decisions based on cradle-to-gate environmental impacts does not necessarily reflect the least cradle-to-grave environmental impact. Until the time when EPDs can cover the full environmental impacts of products, caution should be taken so they are not used as the sole basis of design and procurement decisions.

Notes

1 Learn more about the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), www.congress.gov/117/plaws/publ58/PLAW-117publ58.pdf[8].

2 See the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), www.congress.gov/117/bills/hr5376/BILLS-117hr5376enr.pdf[9].

3 Consult the Executive Order (EO) 14057. 2021, Catalyzing Clean Energy Industries and Jobs Through Federal Sustainability, www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/12/08/executive-order-on-catalyzing-clean-energy-industries-and-jobs-through-federal-sustainability[10].

4 Read the document by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), aclca.org/wp-content/uploads/2022.12.22-Interim-Determination-on-Low-Carbon-Materials-under-IRA-60503-and-60506_508.pdf[11].

5 Visit the Carbon Leadership Forum (CLF). Life Cycle Assessment of Buildings: A Practice Guide, carbonleadershipforum.org/lca-practice-guide[12].

6 Refer to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). ISO 14040:2006, Environmental management—Lifecycle assessment—Principles and framework.

7 Refer to ISO 14044, Environmental management—Lifecycle assessment—requirements and guidelines.

8 Refer to ISO 14025:2006, Environmental labels and declarations—Type III environmental declarations.

9 Refer to ISO 21930:2017, Sustainability in buildings and civil engineering works—Core rules for environmental product declarations of construction products and services.

10 See the British-Adopted European Standard. BS-EN 15804: 2012+A2: 2019, Sustainability of construction works. Environmental product declarations. Core rules for the product category of construction products.

11 Visit the Precast/Prestressed Concrete Institute (PCI). See the Comparative Lifecycle Assessment of Precast Concrete Commercial Buildings: Overview/

Author

Author

Emily Lorenz, PE, F-ACI, is an independent consulting engineer in the areas of lifecycle assessment (LCA), environmental product declarations (EPDs), product category rules (PCRs), green building, and sustainability. She serves as an engineer in the areas of green structures and practices, energy efficiency, thermal properties, and moisture mitigation. Lorenz actively contributes as vice-chair of the Envelope Subcommittee for the 2024 International Energy Conservation Code (IECC), participates in multiple committees including ASHRAE 90.1, ASTM E60, American Concrete Institute (ACI) sustainability, and ISO TC59\SC17\WG3. She is an expert in various technical associations, including ACI and ACI-ASCE Committees, shaping energy conservation codes and environmental product declarations (EPDs). Lorenz received her BS and MS in civil engineering (structural emphasis) from Michigan Technological University.

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Elm-551.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/CradleToGateChart.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Jasper.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Figure-1-Lifecycle-Stages.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Figure-2-summary-of-the-15-building-types.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/O-Street.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Figure_3.jpg

- www.congress.gov/117/plaws/publ58/PLAW-117publ58.pdf: https://www.congress.gov/117/plaws/publ58/PLAW-117publ58.pdf

- www.congress.gov/117/bills/hr5376/BILLS-117hr5376enr.pdf: https://www.congress.gov/117/bills/hr5376/BILLS-117hr5376enr.pdf

- www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/12/08/executive-order-on-catalyzing-clean-energy-industries-and-jobs-through-federal-sustainability: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/12/08/executive-order-on-catalyzing-clean-energy-industries-and-jobs-through-federal-sustainability/

- aclca.org/wp-content/uploads/2022.12.22-Interim-Determination-on-Low-Carbon-Materials-under-IRA-60503-and-60506_508.pdf: https://aclca.org/wp-content/uploads/2022.12.22-Interim-Determination-on-Low-Carbon-Materials-under-IRA-60503-and-60506_508.pdf

- carbonleadershipforum.org/lca-practice-guide: https://carbonleadershipforum.org/lca-practice-guide/

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/evolution-of-sustainable-construction-from-leed-to-federal-mandates/