Evolving foam plastics: Decoding thermal barrier compliance

by arslan_ahmed | February 23, 2024 4:26 pm

[1]

[1]By Richard Barone

Over the past several decades, plastic has been increasingly used in the construction industry, and with more plastics in buildings, the International Building Code (IBC) has updated its requirements to address the flammability of these plastics.

Regarding the proliferation of plastics and composites, the thermal barrier section of the IBC (chapter 26, specifically) came into existence. However, “thermal barrier” is a term used specifically for the fire rating of a building element. It can be confused with terms such as “thermal insulation” or “thermal bridging,” both of which relate to the transfer of heat or cold through building materials. A thermal barrier, however, as defined by the IBC, is very specific to heat and fire.

The Underwriters Laboratories (UL) defines thermal barriers as “a material or product that prevents or delays the ignition of a flammable surface, such as foam plastic insulation or metal composite material, in the event of a fire.”1

The requirements for thermal barriers

The IBC and the International Residential Code (IRC) define approved thermal barriers (“15-minute thermal barriers”) as:

- 12.7-mm (0.5-in.) gypsum wallboards.

- 18.2-mm (0.71-in.) wood structural panel (IRC only).

- A material that is tested in accordance with, and meets, the acceptance criteria of both the temperature transmission fire test and the integrity fire test of NFPA 275.

[2]

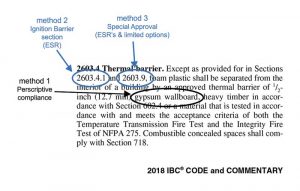

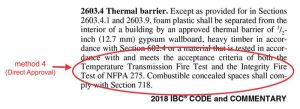

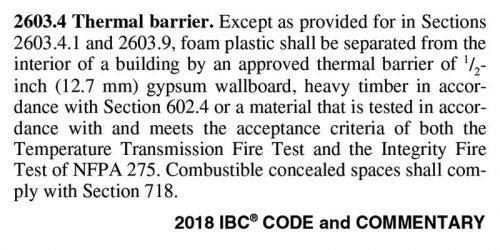

[2]According to the code, all plastics installed into the building envelope require thermal barrier material to be applied over them. IBC section 2603.4 defines thermal barrier, the various deviations and derivatives, and direct compliance approaches to allow plastics to be safely applied in the building envelope.

Addressing thermal barrier requirements

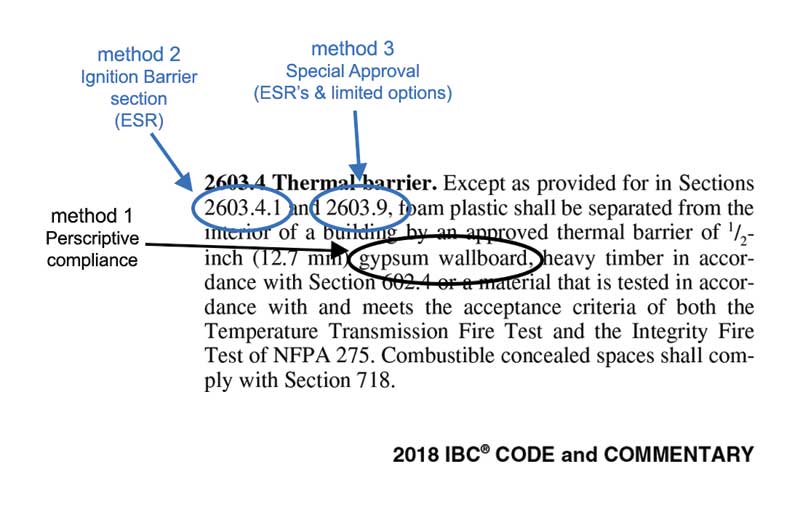

While the IBC defines three methods of permissible thermal barriers, the specific section of the code allows four different methods. These exist primarily due to the unavailability of all solutions and are allowed as deviations until technology catches up with the need for improved fire safety.

There are four methods in which a plastic (and spray polyurethane foam [SPF]) can comply with the code. Figure 2 illustrates three of the four methods: the prescriptive (grandfathered) method in black and two exceptions (deviations) in blue. These exceptions are permitted for specific approaches to meet the code without direct compliance to 2603.4.

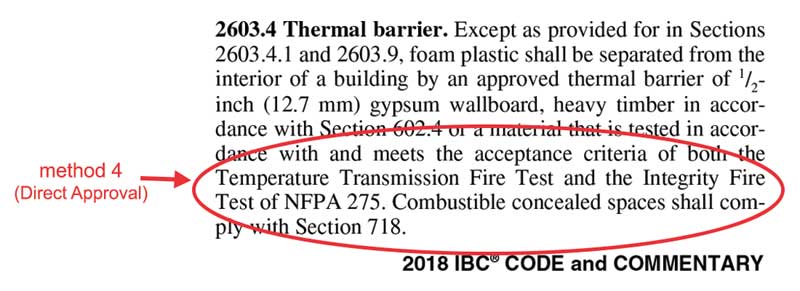

The fourth method, the equivalent compliance method, identifies a multi-test protocol (National Fire Protection Association [NFPA] 275) for achieving an equivalent rating to gypsum (Figure 3). Any product that strives to be equivalent to 12.7 mm (0.5 in.) gypsum must meet this protocol of tests.

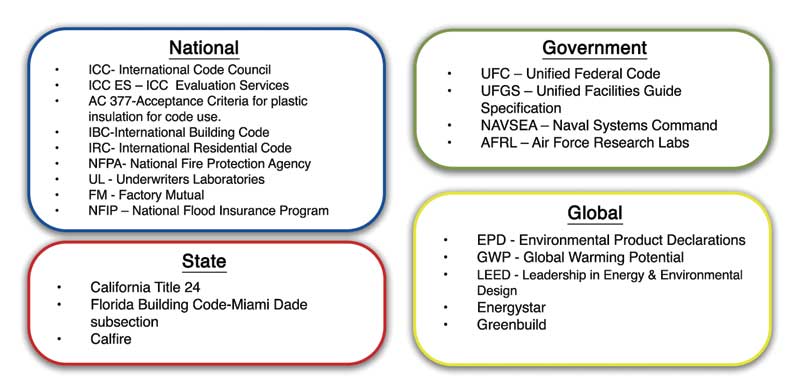

Governing organizations

When one gains an understanding of these four compliance/approval avenues defined in IBC, another layer of complexity forms. There are many governing groups, including global and national organizations, the federal government, and even states that mandate initiatives. Figure 4 (page 36) is an example of the organizations that govern insulation in buildings. Some allow direct interpretation of the IBC and others require stiffer requirements than the IBC or IRC. In many cases, the IBC and IRC are the “minimum required approvals” to be used in the building industry.

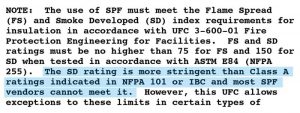

‘Alphabet soup’: Construction compliance-related acronyms

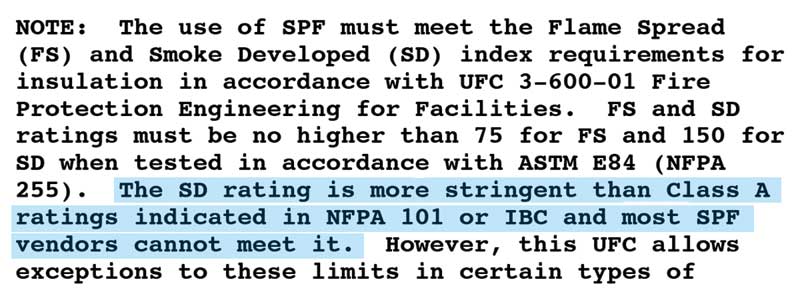

In Figure 5, the alphabet soup of requirements is sometimes conflicting, as section Unified Facilities Guide Specifications (UFGS) 07 27 36 describes. This confuses even the most experienced construction participants. Thus, the information presented here focuses on IBC and IRC code needs only.

Understanding code requirements

Understanding code requirements can be quite overwhelming and even confusing for inspectors and fire marshals, as more complex layers of code are added to the sections around plastics. Keep in mind, the sprayfoam industry is relatively new in the world of construction. Equipment to sprayfoam insulation was only invented in the late 60s (Gusmer created the sprayer in 1962) and its growth and acceptance by construction codes did not exist until the 1970s.2

As expected with so many governing organizations, many of which overlap and cover different domains in the construction industry, SPF serves many masters. Compliance gets quite complicated, trying to supply all the documentation required, especially for the two exception-based compliance methods.

Direct compliance with gypsum, where feasible, is a much easier and cost-effective execution. Historically, equivalent thermal barriers were “add-ons” to the SPF and inherently added cost, labor, and inspection/documentation steps. As codes have changed, the challenges for compliance with these approval methods are continually tested. Specific examples of how each of these entities drive different compliance requirement challenges include:

- Some states are now requiring the installation of R-30 in walls and R-60 in ceilings, which requires almost 508 mm (20 in.) of fiberglass or mineral wool insulation.3 Some buildings cannot even support the depth of bays required.

- The National Flood Insurance Program (and FEMA) require only closed-cell SPF in any cavity which might be exposed to water.4

The good news is there are other energy-based codes addressing more sustainable and energy-friendly solutions such as closed-cell sprayfoam, and specifically, a new generation of single-step thermal barrier SPF technologies. One example is the International Energy Conservation Code (IECC), which provides for significantly less continuous insulation (c.i.) material when using an energy performance/savings measure for insulation and building envelope challenges.

‘Add-on’ products over plastics

SPF has historically met the code by being applied behind gypsum or covered with approved, add-on thermal barriers such as cellulosic and cementitious materials. SPF could also comply with code through “exception” methods using the lower-level ignition barrier approval (method two) or special approval testing (method three) via intumescent coatings as well.

When choosing one of these methods, commonly asked questions are:

- Which test(s) should be used?

- Which combination of coatings or cellulose or cementitious materials should be used?

- Over which foams?

- At which thickness?

- In which densities?

Addressing all the combinations of SPF/coating/cellulose/cementitious solutions and the appropriate paperwork needed for building officials is a separate topic in and of itself, requiring further discussion and explanation. However, understanding the add-on solutions is crucial and does need to be taught, as each skilled trade bears the responsibility for the safety of the construction process and the end-result.

One overriding thought to keep in mind is that manufacturers who supply plastics for the building envelope often claim their products are “fire-rated,” and although overly vague and misleading, they are partially correct. All plastics require a minimal level of fire rating to even be allowed for use in buildings. The problem is the robustness of the test procedures they reference.

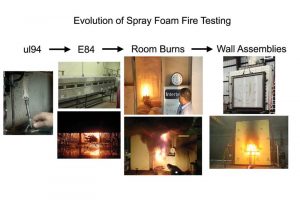

Figure 6 shows a range of common fire tests that companies reference. A company could claim a “fire rating” from a simple Bunson burner test lasting only seconds, to full wall assemblies and ceilings that have achieved multi-hour ratings. Tests lasting mere seconds or claiming “self-extinguishing” properties with low-level heat or flame impingement provide less than acceptable protection for life safety.

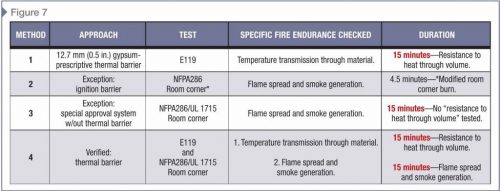

Even when companies claim adequate fire approvals within the jurisdiction of 2603.4 (usually as a function of time), the test behind the measure can be confusing and/or inaccurately communicated, creating confusion and potential safety violations. A clear example of this confusion is the pass/fail time requirements (Figure 7) of exception tests (method three) versus the gypsum approval (method one) versus the equivalent thermal barriers (method four).

Prescriptive method one (gypsum) follows historical performance results and fire ratings are 15 minutes long, based on ASTM E119, Standard Test Methods for Fire Tests of Building Construction and Materials. This is also sometimes called the compartmentalization of the fire test. It tracks and defines the time it takes for extreme heat to pass through a wall or ceiling to create a fire-risk situation in adjacent rooms to the space that have been compromised by fire.

Exception method three (special approval) defines a 15-minute period where flame spread and smoke generation from a known fire source in a 2.4 x 3.6 m (8 x 12 ft) room cannot exceed certain critical safety levels of flame and smoke. The flame and smoke growth maximums over the 15-minute duration estimate a safe amount of time to evacuate the space. Method three almost always defines systems’ (e.g. foam and coating together) capabilities which work in conjunction to achieve a exception level but “code-allowed” solution to life safety, but does not show compliance to temperature transmission risk in a structure. Although both test programs have 15-minute durations, they certify two very different life-safety criteria that are not interchangeable.

Direct compliance, method four (NFPA 275, also known as “equivalent thermal barriers”), is a test protocol that requires both tests—the temperature transmission test and the flame spread smoke generation test—both over a period of 15 minutes. Method four establishes a combination of both the prescriptive solution and the special approval solution and defines an equivalent thermal barrier to the gypsum prescriptive method.

All of these choices relate to a life-safety and liability issues; therefore, it is imperative for the builder, architect, or general contractor to understand the various fire-rating methods and what they mean in order to protect themselves. Alternatively, find a trusted compliance partner, a fire consultant, or a fire inspector.

The SPF insulation industry has not been standing idly regarding the emerging requirements and changing code needs. It is finding ways to improve fire resistance. It is proving compliance to environmental/sustainable/planet-saving initiatives. SPF is the best solution for addressing the challenges of less CO2 emissions and less energy losses in buildings, which are one of the largest contributors to global warming.5 Post-applied thermal barriers and cost increases associated with them have made the expansion of standard SPF into broader markets slowly. New, all-in-one thermal barrier sprayfoam technologies help solve many of these challenges, and effectively provide better value.

Emerging sprayfoam insulation technologies

Monolithic fire performance

Some emerging SPF products are striving to achieve better fire performance, monolithically, in foam insulation. These new, monolithic SPF products pass NFPA-275 thermal barrier tests, thus being thermal barriers and c.i. Since the foam is a composite homogeneous solid, when it meets NFPA-275 requirements, it is a fire and thermal protective barrier throughout the complete volume of the insulation all-in-one. Having its fire characteristics throughout its complete volume means fewer added steps, cost, and risk, versus a thermal barrier coating, cellulose, etc.

Post-applied “exception-based” thermal barriers become daunting when trying to ensure compliant, safe application. First and foremost, they need to be properly applied. Second, proper application requires third-party inspection. Next, they can only be used in what is referred to as “conditioned spaces,” which are dry, heated environments lest they are prone to field failures. Finally, as soon as the surface is breached in any way, shape, or form, the fire barrier characteristic of the flammable substrate is lost.

A monolithic fire barrier material will also protect against fires from the outside in, as well as fires from the inside out. Topcoats only protect one face of flammable insulation; they cannot provide unilateral fire protection from wildfires (externally initiated fires), electrical shorts, wall fires, lightning strikes, etc.

[3]

[3]This technology is now presenting itself in the market. By taking a continuous sprayfoam and incorporating innovative, fire-addressing thermal barrier protective technologies within the foam, one can attain all the benefits of c.i., air barrier, moisture barrier, mold defense, structural rigidity, and high insulation value in their structures.

Reducing risk window

How does this benefit the owner, the general contractor, the architect, insurers, and/or the spray application company? Sprayfoams react in the field through a two-component chemical reaction. The NFPA-275 fire barrier rating of the new foam becomes an effective fire barrier as soon as the chemical reaction finishes. Fire safety is “built-in” as soon as the reaction is complete. This is what is known as a “zero risk window” product and is very different from what happens currently when flammable plastic insulation materials, both panels and continuous, must wait for a thermal barrier to be applied.

Often, the company providing the thermal/fire barrier is not the same company applying the insulation. This presents the issue of who owns the liability during that in-between, safety risk window period. Also pertinent is who ensures the proper application methods of the post-added thermal barrier and which code requirements are being met. This risk affects everyone in the construction phase, from the architect to the contractor, sprayfoam applicator, insurance company, and owner/end-user. The risk, added materials, labor, governance, and complexity are eliminated with NFPA-275 SPFs.

[4]Increasing fire resistance

[4]Increasing fire resistance

Another radically new and often overlooked paradigm credited to monolithic NFPA-275 SPFs is the ability to increase the fire resistance of a building wall or ceiling system. Historically, this has been reserved for non-combustible building elements such as brick, stucco, and concrete. With the achievement of method four (Figure 6), NFPA-275 SPF reduces the transmission of temperature through wall and ceiling assemblies. It passes the ASTM E119 temperature transmission tests described earlier (Figure 7), the method used to define wall ratings (i.e. when an inspector says a one-hour wall is needed between a garage and a house).6 As the thickness of the monolithic fire barrier SPF increases, so does its ability to delay the transmission of heat and poisonous fumes, increasing the overall wall system’s hour rating.

This extends the thermal barrier SPF into the realm of fireproofing; something foam could never be used for in the past. That benefit has historically been reserved for gypsum, concrete, cementitious, brick, and stone. This new technology opens many new and creative avenues previously unattainable with foam insulation in concert with the non-combustible materials described above.

Embracing the benefits

At the end of the day, architects, builders, contractors, and even end-users care about better value. NFPA-275 thermal barrier high-R insulation products cost slightly more initially, but the total costs, including the speed of installation, the overall quality, and end-user impact generate significant value across the complete construction hierarchy, resulting in significant cost savings. As with any new, emerging technology, the costs will decrease as market penetration increases.

To date, these new technologies are not optimized for all situations. However, they are already radically improving total costs and margins in several major areas of construction such as commercial, government, union, and prevailing wage projects. These benefits translate into other large fringe areas, which also need an increased focus in safety such as agriculture, commercial cold storage facilities, grow houses, outbuildings, military, and aviation hangers.

The elimination of steps in these larger, more complex initiatives translates to lower costs, better solutions, and most importantly, a lower risk for the loss of life and property—a true trifecta of value. Remember what is really at stake. It is not just a code issue, it is a life safety issue.

Notes

1 Refer to www.ul.com/services/thermal-barrier-testing-and-certification[5].

2 See the polyurethanes timeline at www.polyurethanes.org/what-is-it/[6].

3 To learn more, read litchfieldbuilders.com/the-importance-of-proper-insulation-in-connecticut-homes-and-how-to-achieve-it-through-renovation[7].

4 Visit www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/risk-management/building-science/national-flood-insurance-technical-bulletins, and see table 2 at fema_tb_2_flood_damage_resistant_materials_requirements.pdf[8].

5 Refer to www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/02/decarbonizing-buildings-climate-change-infrastructure[9].

6 Learn more at codes.iccsafe.org/content/IBC2021P1/chapter-7-fire-and-smoke-protection-features, section 708[10].

Author

Author

Richard Barone Jr. is co-founder and executive vice-president of operations for Firestable Insulation Co. As an entrepreneur and inventor, he has established several fire technology companies in his 20-plus years in fire protection.

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Texas-metal-building-using-Firestable-2.0.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/11.29.23-Figure-1-Hi-Res-copy.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/11.29.23-Figure-6-Hi-Res-copy.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/figure-7.jpg

- www.ul.com/services/thermal-barrier-testing-and-certification: https://www.ul.com/services/thermal-barrier-testing-and-certification

- www.polyurethanes.org/what-is-it/: https://www.polyurethanes.org/what-is-it/

- litchfieldbuilders.com/the-importance-of-proper-insulation-in-connecticut-homes-and-how-to-achieve-it-through-renovation: https://www.litchfieldbuilders.com/the-importance-of-proper-insulation-in-connecticut-homes-and-how-to-achieve-it-through-renovation

- www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/risk-management/building-science/national-flood-insurance-technical-bulletins, and see table 2 at fema_tb_2_flood_damage_resistant_materials_requirements.pdf: https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/risk-management/building-science/national-flood-insurance-technical-bulletins,%20and%20see%20table%202%20at%20fema_tb_2_flood_damage_resistant_materials_requirements.pdf

- www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/02/decarbonizing-buildings-climate-change-infrastructure: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/02/decarbonizing-buildings-climate-change-infrastructure/

- codes.iccsafe.org/content/IBC2021P1/chapter-7-fire-and-smoke-protection-features, section 708: https://codes.iccsafe.org/content/IBC2021P1

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/evolving-foam-plastics-decoding-thermal-barrier-compliance/