Exploring how sound and noise impact wellbeing in office design

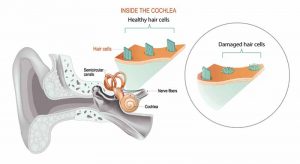

Non-auditory health effects

Fewer people are aware of the potential non-auditory health risks of lower-level noises, below the established thresholds that one associates with hearing impairment. Over the past decades, researchers started exploring the impacts of various sources (e.g. road, rail, and airplane traffic), and the results are mixed. As a general, non-specific stressor, noise has been found to have non-auditory health effects—such as changes in hormones, sweat response, metabolism, heart rate, and blood pressure, as well as outcomes related to its disruptive effect on sleep and immune response—but not consistently. Further, it is difficult to conclusively link noise to, for instance, the development of heart disease, which can also be linked to other health-related factors.

This is not to say there are no such adverse impacts; in fact, some experts maintain the question is no longer whether noise causes cardiovascular disease, for example, but to what extent.

Noise sensitivity

Research consistently demonstrates noise level alone is not a sufficiently strong indicator of potential health consequences. One must also take into consideration additional characteristics such as frequency, predictability, complexity, duration, and the meaning of the noise in question, the listener’s acoustic environment (including ambient or background spectra and levels), and the listeners themselves—perhaps first and foremost, their sensitivity to noise.

A growing body of literature dealing with the non-auditory effects of lower-level noise differentiates between “noise exposure” and “noise sensitivity.” In a review, Brown et al. cites Schreckenberg et al., who found that noise affects different people differently, as well as Shepard et al., who “found noise level does not necessarily determine noise annoyance, but rather other factors play a role, in particular, noise sensitivity.”4 The findings, presented by Park et al. (2017) in a paper titled, “Noise sensitivity, rather than noise level, predicts the non-auditory effects of noise in community samples: a population-based survey,” show the effects—specifically those pertaining to mental wellbeing—on an individual’s health are more strongly correlated with their sensitivity to noise than other variables (e.g. sociodemographic factors, medical illness, duration of residence, and so on).

Although the focus of such research largely remains an assessment of the person (a comprehensive description of the acoustic conditions is seldom provided), distinguishing between noise exposure and noise sensitivity has advanced understanding of the non-auditory effects of noise and led more researchers to question whether different people react similarly—or the extent to which they do—when exposed to lower-level sources, and to focus on the psychological, as well as the physical, impacts.

Neurodiversity and noise

Researchers are also exploring how individual differences come into play within the workplace. For example, neurological differences—such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), dyslexia, and dyspraxia, as well as neurological challenges resulting from brain injury—can impact how individuals process sensory information (e.g. increase noise sensitivity), which in turn affects their social and occupational functioning. Employees can also suffer from misophonia, or other auditory hypersensitivities, whereby common sounds such as chewing, breathing, and repetitive tapping—or stimuli related to such sounds—elicit a strong emotional response ranging from mild irritation to anxiety, anger, disgust, and even significant distress.